This creation of new administrative districts by splitting existing districts is a frequent occurrence in India, where the number of districts has more than doubled in the last four decades. Looking at data from 1991 to 2011, this article considers the effect of this fragmentation on economic outcomes. It finds that impacted districts tend to be more homogenous than before; the split is especially advantageous for newly created districts, which reap the redistributive benefits of bifurcation.

Sub-national administrative boundaries in many developing countries are fluid. Administrative proliferation or government fragmentation involves carving out new states, districts, sub-districts, etc. This creation of new administrative units by splitting existing ones at subnational levels is commonplace (Grossman and Lewis 2014). Since the 1950s, India has seen frequently created new districts. While the nation had 356 districts in 1971, and 640 in 2011, the number of districts has since grown to 7801. The stated reasons for creating new districts are administrative ease and better developmental outcomes by bringing the state closer to the citizens (Asher et al. 2018, Brinkerhoff et al. 2018).

District creation in India: Trends and implications

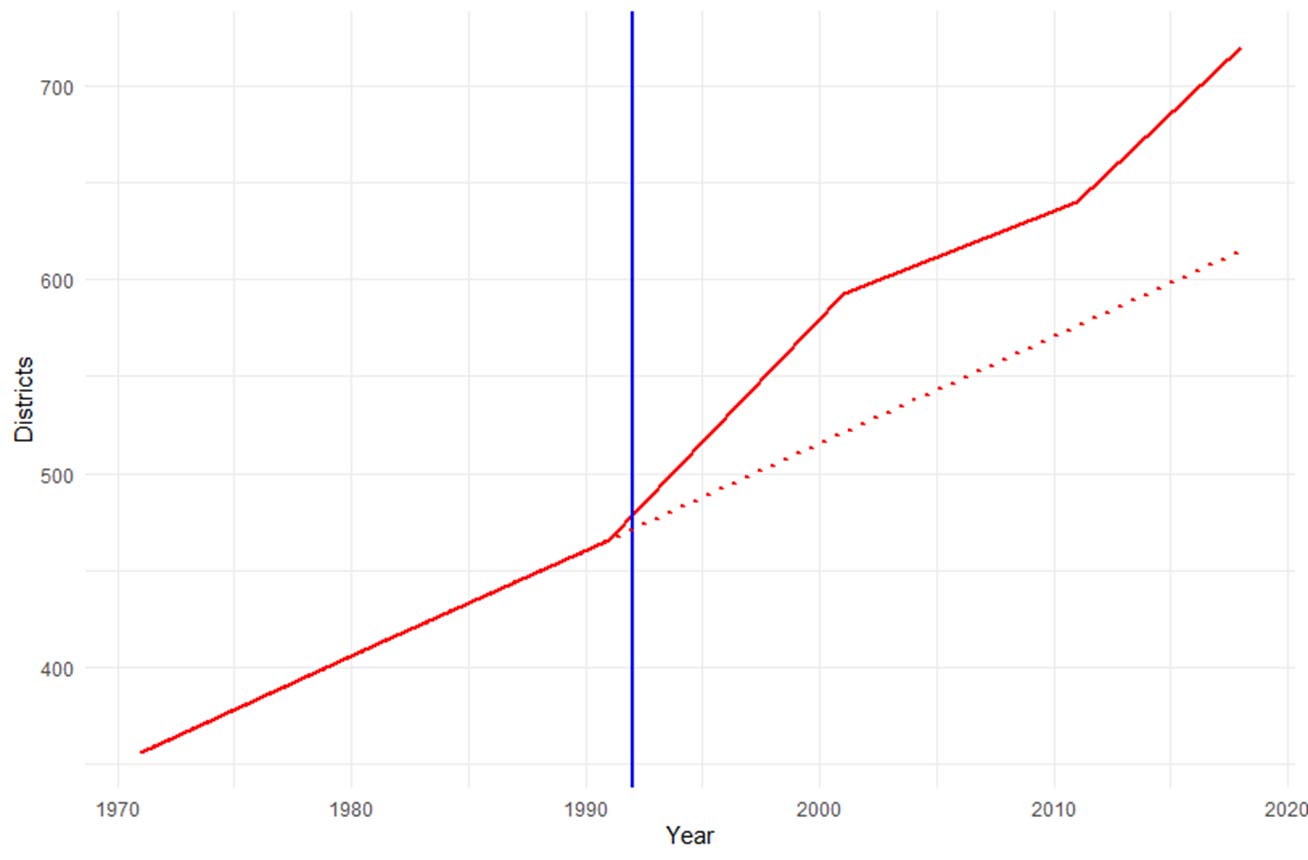

There is an unmistakable trend towards creating more districts, which has picked up pace since the Panchayati Raj amendments2 in 1992 (see Figure 1). It has been theorised that once decentralisation reforms are implemented, the benefit from controlling each sub-national unit increases, and there is incentive for local elites to demand the creation of new units (Grossman and Lewis 2014).

Figure 1. Pace of district creation in India

Note: The blue line corresponds to the year of introduction of the Panchayati Raj amendments of 1992. The red line graphs the number of total districts in India across years. The red dotted line is a projection of the total districts according to the trend up till 1990.

Although administrative proliferation is often associated with decentralisation reforms, it is a distinct policy choice. Decentralisation involves the devolution of responsibility, authority, and resources to lower-level governmental units (Falleti 2013), while administrative proliferation only creates new governmental units without changing the underlying fiscal and administrative structure (Grossman and Lewis 2014, Grossman et al. 2017). However, creating new districts brings citizens closer to their administrators and makes each district smaller and more homogeneous in terms of ethnicity and preferences, theoretically leading to better development outcomes (Pierskalla 2019).

Empirical work has explored the role of electoral politics in administrative proliferation (Resnick 2017) and the effect of administrative proliferation on conflict and violence (Pierskalla and Sacks 2017, Bazzi and Gudgeon 2021). However, the available evidence on the effects of administrative proliferation on developmental outcomes has been mixed (Carlitz 2017, Lewis 2017, Billing 2019, Halimatusa’diyah 2020). In our recent work (Rajan and Malghan 2022), we contribute to the empirical evidence on the developmental outcomes of district proliferation using sub-district level data from India.

New districts in India are created by the respective states, by assigning a few sub-districts from an existing district as a new district, and by choosing one of the sub-districts from the new unit as the district headquarters3. Therefore, since districts are created by reallocating sub-districts and by assigning a new administrative headquarters, administration below the district level does not change, but infrastructure for new district headquarters is created.

Findings

Using data collected on public goods provisions and social category in the districts of India over two census periods (from 1991 to 2011), and night-time luminosity measures4 during the same period, we investigate whether there are observable differences in terms of ethnic composition and economic outcomes between the districts that are chosen to be newly formed and the ones that remain. We computed two demographic variables from the census population data – a fractionalisation5 and a spatial dissimilarity6 index.

At a sub-district level, the category-wise7 (SC, ST, OTH) population distribution is likely to be different from that of a higher administrative unit such as a district. We find that sub-districts in districts that were split (both ‘parent’ and ‘child’ districts) are different from those in regions that did not split. We compared economic outcomes and ethnic distribution of split districts with that of unsplit districts, while controlling for other demographic and economic variables such as share of urban population, share of agricultural labour, share of literate population, and indicators of public goods such as the number of primary schools and primary health centres in the subdistrict.

Both fractionalisation and dissimilarity were greater in split districts, and the differences were statistically significant. Similarly, we compared the economic outcomes of the regions before bifurcation, using an indicator which measures if the average night-time lights in the subdistrict is higher than the district of which it is a part. Within a split district, marginalised areas with a higher level of dissimilarity and lower levels of economic outcomes are more likely to split off and form a new district in the future.

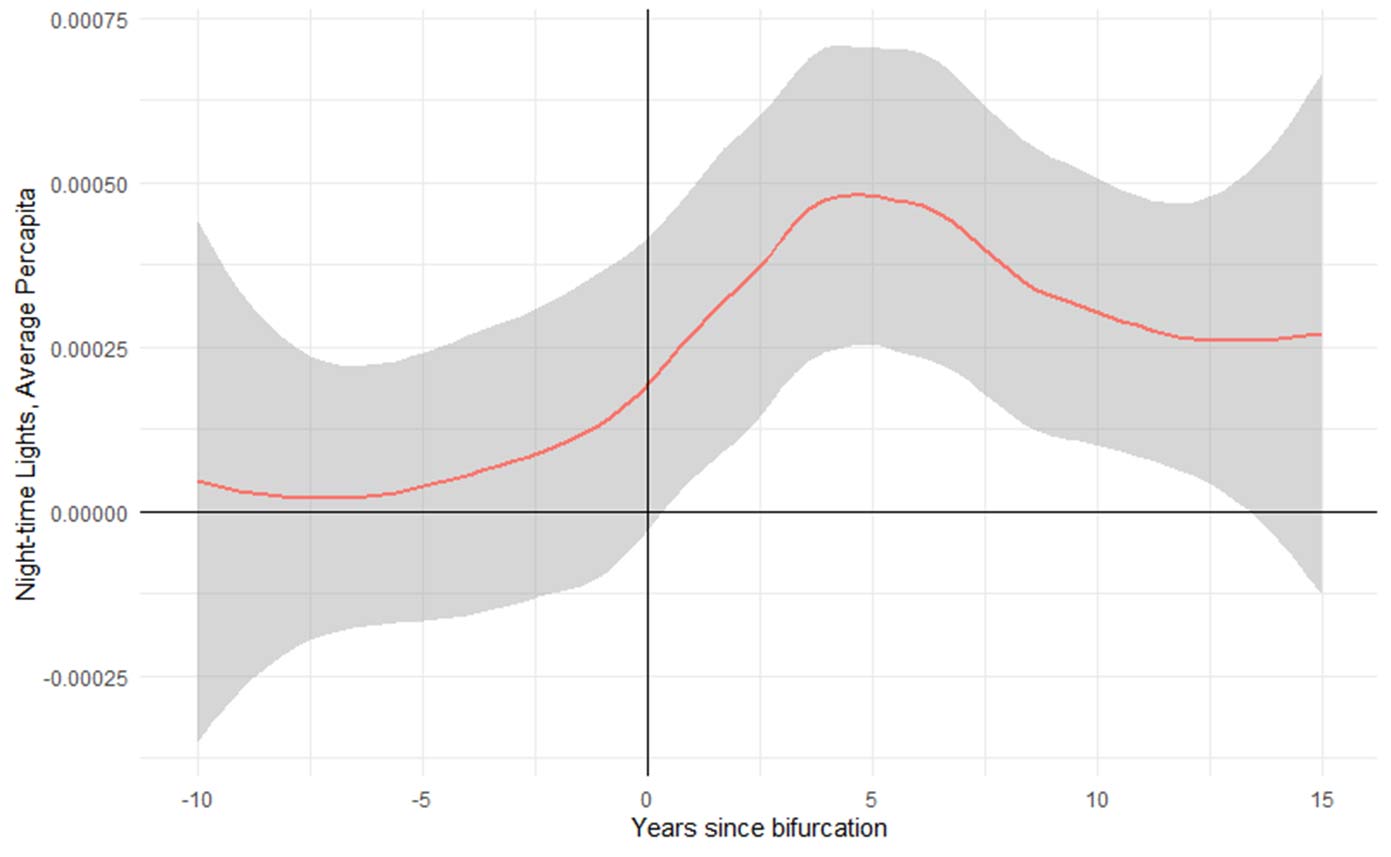

We also explore whether the newly created ‘child’ districts have better developmental outcomes compared to the part that remained with the erstwhile ‘parent’ districts. We find that ‘child’ districts do significantly better than the ‘parent’ district, in economic outcomes, measured in night-time lights. The effect persists for a few years, and then tapers off. We also find that district that were split – both parent and child districts – do better than district that were never split.

Figure 2. Difference in per capita night-time lights for ‘child’ and ‘parent’ districts

Note: The figure plots the difference between the average per capita night-time lights of the child districts and the parent districts in the years before and after the bifurcation.

Implications

Our findings support the hypothesis that district bifurcations are beneficial for the overall district – and especially newly created districts – in terms of economic output. There could be two underlying mechanisms for the observed effects – it may be arising due to the greater homogeneity in population distribution after the split, or due to the redistributive benefits of bifurcation.

After the bifurcation, both the child and the parent region tend to be more homogeneous than before. We find that when compared with a similar district that was never split, both child and parent districts do better in terms of economic outcomes. This suggests that that the greater homogeneity in population distribution and preferences after the split could be playing a part in the observed outcomes.

However, the child regions do better than the parent regions in the post bifurcation period. This is reasonable to expect, because the villages in the child district gain an additional advantage of having a new administrative setup built closer to them. This is consistent with the findings of Asher et al. (2018), who suggested that reducing the distance between citizens and administrative centers could lead to better outcomes using data from India. The parent region already has an established administrative system, and therefore the redistributive effects due to the creation of a new district headquarters do not come into play in the parent district. The observed benefit to the child region over the parent region seems to suggest that the observed effects are due to redistributive benefits. Thus, our findings suggest that both the mechanisms of population homogeneity and redistributive effects are at play in district bifurcations.

We note here that government functions are many and varied, and the effect of population size on one of those functions might not be the same as that on others. As such, this study limits its comments on local government size to general economic outcomes as measured by night-time lights, without commenting on the performance of local governments with respect to other functions and services, or the efficiency and cost of service delivery. Administrative proliferation as a policy measure has mixed results with specific public service measures such as education, sanitation, water supply, or maternal health (Carlitz 2017, Lewis 2017, Billing 2019, Halimatusa’diyah 2020). Although the population per district in India is high, and as such the observed effects of administrative bifurcations may fall off at lower levels of population per administrative unit, the findings from this study suggest some positive aspects of administrative proliferation.

Notes:

- As of August 2022.

- The 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts establish a three-tier system of local self-government, with the Gram Sabha (consists of all persons registered in the electoral rolls in a village or set of villages) as its foundation, to perform functions and powers entrusted to it by the State Legislatures

- For example, a new district Chamarajanagar was created from the existing Mysore district in Karnataka in 1997 in Karnataka State. Of the 11 sub-districts in Mysore, four were transferred to and formed into a new district, with the Chamarajanagar sub-district assigned to be the new headquarters.

- Night-time luminosity is often chosen as a proxy for economic output because it is highly correlated with output, available at high resolutions, and can be uniquely linked to human activities (Chen and Nordhaus 2011).

- Fractionalisation is a measure of the probability that two randomly chosen individuals will belong to two different social categories – ẖere, SC, ST or OTH. Fractionalisation is high if the different social groups in the region are all more or less equally strong in terms of population. If one groups dominates numerically then the region is less fractionalised.

- Dissimilarity is a comparison metric of the fractionalisation of the sub-district with the fractionalisation of the district within which it is located. Dissimilarity tells us whether the sub-district has a different demographic distribution from the district within which it is located.

- The census data provides population data in three categories – scheduled castes (SC), scheduled tribes (ST) and others (OTH).

Further Reading

- Asher, S, K Nagpal and P Novosad (2018), 'The Cost of Distance: Geography and Governance in Rural India', World Bank Working Paper.

- Bazzi, Samuel and Matthew Gudgeon (2021), "The political boundaries of ethnic divisions", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 13(1): 235-266.

- Billing, Trey (2019), "Government Fragmentation, Administrative Capacity, and Public Goods: The Negative Consequences of Reform in Burkina Faso", Political Research Quarterly, 72(3): 669-685.

- Brinkerhoff, Derick W, Anna Wetterberg and Erik Wibbels (2018), "Distance, services, and citizen perceptions of the state in rural Africa", Governance, 31(1): 103-124.

- Carlitz, Ruth (2017), "Money flows, water trickles: Understanding patterns of decentralized water provision in Tanzania", World Development, 93: 16-30.

- Chen, Xi, and William D Nordhaus (2011), “Using luminosity data as a proxy for economic statistics”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(21): 8589–8594.

- Falleti, T (2013), 'Decentralization in time: A process-tracing approach to federal dynamics of change', in A Benz and J Broschek (eds.), Federal Dynamics: Continuity, Change, and the Varieties of Federalism.

- Grossman, Guy and Janet Lewis (2014), "Administrative Unit Proliferation", American Political Science Review, 108(1): 196-217.

- Grossman, Guy, Jan H Pierskalla and Emma Boswell Dean (2017), "Government fragmentation and public goods provision", The Journal of Politics, 79(3): 823-840.

- Halimatusa’diyah, Iim (2020), "Does local government proliferation reduce maternal mortality? Evidence from Indonesian sub-national government", Asian Politics & Policy, 12(4): 592-616.

- Lewis, Blane (2017), "Does local government proliferation improve public service delivery? Evidence from Indonesia", Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(8): 1047-1065.

- Pierskalla, J (2019), 'The proliferation of decentralized governing units', in In J Rodden and E Wibbels (eds.), Decentralized governance and accountability: Academic research and the future of donor programming, Cambridge University Press.

- Pierskalla, Jan and Audrey Sacks (2017), "Unpacking the effect of decentralized governance on routine violence: Lessons from Indonesia", World Development, 90: 213-228. Available here.

- Rajan, J and D Malghan (2022), 'Administrative Proliferation and Developmental Outcomes: Data from India', IIM Bangalore Research Paper No. 658.

- Resnick, Danielle (2017), "Democracy, decentralization, and district proliferation: The case of Ghana", Political Geography, 59: 47-60.

08 August, 2022

08 August, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.