Employment in India’s organised manufacturing sector has grown rapidly since 2004. This article finds that about 15% of this growth can be attributed to the formalisation of previously informal enterprises, and expects that, as the new labour code is implemented, the output and employment of relatively bigger informal manufacturing establishments will rise significantly, with concomitant gains in productivity. The productivity potential of such informal enterprises needs to be adequately exploited with investment in ICT and other fixed assets.

The Indian government has taken several measures to formalise the informal economy of India (see Unni (2018)), including the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the digitisation of financial transactions, and implementing the Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan Yojana and Aatmanirbhar Bharat Rozgar Yojana.1 The need for formalising the informal economy in India has been widely recognised2 – besides the various other benefits, the process of formalisation is itself important to ensure a wider prevalence of decent work.

The informal segment within manufacturing in India is about a quarter of the sector in terms of gross value added (GVA), and about three-fourths in terms of employment.3 In 2017-18, the share of the informal sector in manufacturing GVA was about 34% (Krishna et al. 2022). According to the NSO’s Annual Survey of Industries (ASI)4, in 2015-16, employment in organised manufacturing was about 13.6 million, According to the 73rd round of the National Sample Survey (NSS) data on unincorporated non-agricultural enterprises, there were an estimated 36 million workers in unorganised or informal manufacturing (that is, the unincorporated segment outside the coverage of the ASI) in 2015-16. Thus, the share of informal enterprises in manufacturing may be placed at about three-quarters. According to the India KLEMS database, the total employment in manufacturing in 2018-19 was about 54 million.5 Based on this estimate of aggregate employment in manufacturing in India, the share of the informal enterprises in employment in manufacturing was about 70% in 2018-19.

Rapid employment growth and structural change

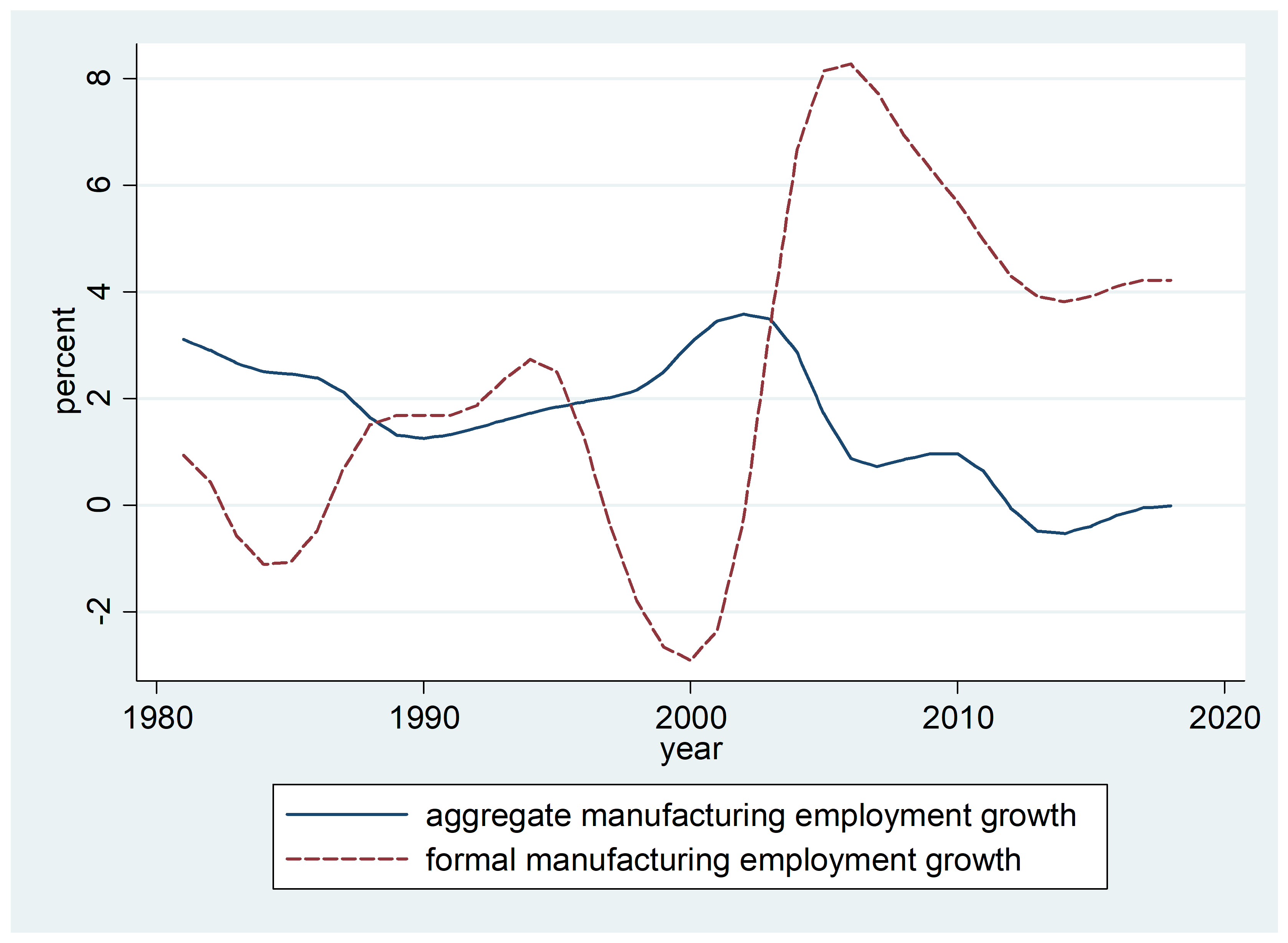

There was a significant break in employment growth in India’s formal manufacturing in 2004-05 (see Figure 1). In the period between 2004-05 and 2018-19, the average annual growth rate in employment in India’s formal manufacturing (according to the ASI) was quite impressive at about 5% per annum. By contrast, according to the India KLEMS database, the growth rate in aggregate manufacturing employment during 2004-05 to 2018-19 was only about 0.3% per annum. Thus, the structure of employment in manufacturing has been shifting from the informal sector to the formal sector in the last fifteen years, with the share of the formal sector rising from about 16% in 2004-05 to about 29% in 2018-19 (that is, nearly doubling in this period).

Figure 1. Employment growth rate in formal manufacturing and aggregate manufacturing, smoothened

Informal to formal: Capturing the transformation of enterprises

Despite the importance of documenting and understanding the process of transformation of informal sector manufacturing enterprises into formal sector manufacturing enterprises in India, there is very little data available on the magnitude of the transformation taking place (in this context, see Nagaraj and Kapoor (2022)). The basic data source on manufacturing plants in India is the ASI. However, this does not provide data on how many factories were newly registered under the Factories Act, 1948 in every year, and whether they were engaged in the production of industrial goods before their registration. This could have thrown some light on the extent of formalisation of the informal manufacturing enterprises taking place in the country.

In a recent paper (Goldar 2023), I estimate the employment generated in India’s formal manufacturing sector as a result of the transition of informal sector manufacturing enterprises into formal sector manufacturing enterprises, based on unit-level data of ASI.

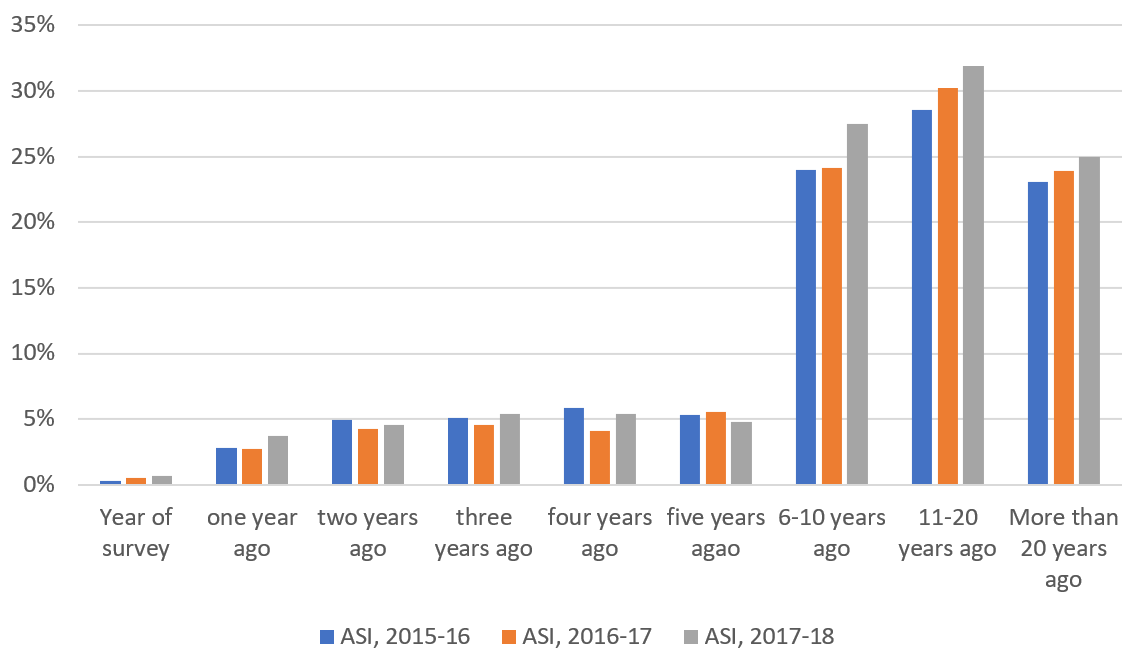

Average employment in India’s organised manufacturing during the period between 2015-16 and 2017-18 went above that of the triennium of 2005-06 to 2007-08 by 4.7 million. About 15% of the increase in employment can be attributed to the transition of informal manufacturing enterprises to formal manufacturing enterprises. It was discovered while examining the unit-level data of ASI, that a portion of the factories covered in the survey for 2015-16 have not been covered previously in any of the surveys from the year 1998-99 to 2014-15 (these are ‘newly surveyed’ factories). In the same way, newly surveyed factories are identified for 2016-17 and 2017-18, and the year of initial production is tabulated for all these factories. The distribution obtained is presented in Figure 2. It can be noticed that a dominant portion of the newly surveyed factories started production 11 to 20 years ago, or even earlier.

Figure 2. Distribution of newly surveyed factories by year of initial production

Selecting factories for the ASI frame

In the ASI surveys, the Census Sector factories (that is relatively bigger factories, that generally employ 100 workers or more) are completely enumerated, while the Sample Sector factories are covered based on probability sampling. The ASI frame is dominated by the Sample Sector factories. As a rule of thumb, the probability that a particular factory existing in the ASI frame will get selected for the survey in a particular year maybe 10%. Thus, there is a 90% chance that a factory will not get selected. If a factory is in the ASI frame and remains there for the next ten years, the probability of it not getting selected in ten consecutive ASI surveys is 0.35.

It follows that a substantial portion of the factories that were surveyed in ASI for the first time during 2015-16 to 2017-18, but had started production 10 years ago or earlier, had escaped being surveyed because they were initially in the informal sector, and registered later, under the Factories Act, 1948. To be on the safe side, this proportion has been taken as one-quarter of all the newly surveyed factories that started production at least five years before the year when they were surveyed. On this basis, an estimate of employment in the factories that moved from the informal sector to the formal sector has been made.

Size-wise distribution within informal manufacturing

It is difficult to estimate the number of factories that have transitioned from the informal manufacturing sector to the formal manufacturing sector. If a guess must be made, this was probably somewhere in the range of five to ten thousand factories each year during 2015-2017. This is a very small number compared to the total number of manufacturing enterprises in the informal sector (which was about 19.7 million in 2015-16). This holds true even if a comparison is made with the number of informal sector manufacturing establishments (those having at least one hired worker), which was about 2.9 million in 2015-16. The number of manufacturing establishments transitioning from the informal sector to the formal sector is thus a very small fraction of the total number of establishments existing.

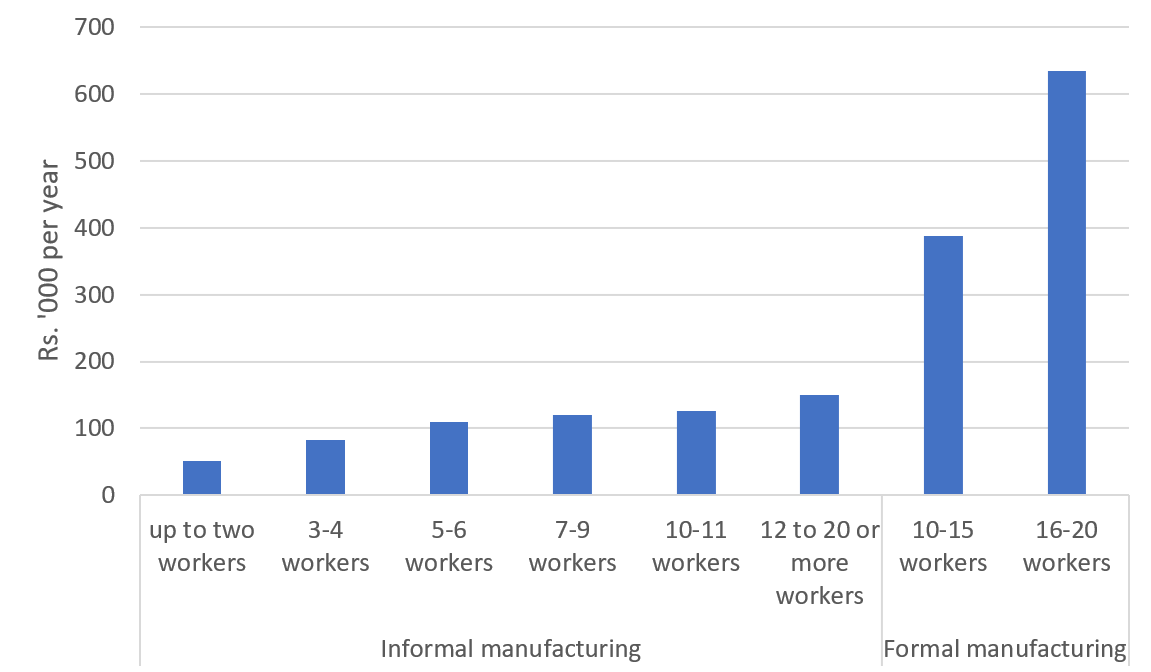

Enterprises employing between seven and nine workers constituted about 9% of the total number of establishments in informal manufacturing in 2015-16, and those employing 10 or more workers (in many cases, even more than 20 workers) formed about 7%. As the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020, gets implemented in the country – replacing the Factories Act, 1948 and several other labour laws – the share of establishments with upto 19 workers in informal manufacturing is expected to go up: enterprises can employ more workers and reap economies of scale without attracting the provision of the new codes since the applicable threshold for certain provisions will be raised from 10 to 20 (for factories with power) or from 20 to 40 (for factories without power) (Bhattacharjea 2023). This is also likely to raise the average productivity level of informal manufacturing establishments. However, it is important to recognise that the labour productivity of enterprises in the informal manufacturing in the size class of 10 to 20 workers is much lower than that of the same size class in formal manufacturing (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. GVA per worker in informal and formal manufacturing, in 2015-16

However, this is not a handicap but represents the productivity-enhancing potential of formalisation, which is yet to be exploited by the majority of enterprises. It also points to the need for adopting policies that encourage and facilitate enterprises in unorganised manufacturing to make more investments in fixed assets, including information and communication technology (ICT) assets.6

Notes:

- The Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan Yojana (PMRPY) was implemented in 2016 with the objective to incentivise employers to create new employment and bring informal workers to the formal workforce. Aatmanirbhar Bharat Rozgar Yojana (ABRY) was launched to incentivise the creation of new employment, along with social security benefits and restoration of loss of employment during the Covid-19 pandemic. See, press release of the Press Information Bureau, Government of India dated 17 March 2021 for more information.

- In 2015, the International Labour Organization (ILO) adopted recommendation No. 204 about the transition from the informal to the formal economy. The ILO also has a project on facilitating the formalisation of the informal economy in South Asia.

- A simple distinction is being made here between formal and informal manufacturing, as in several earlier studies, based on the registration under the Factories Act, 1948. The issue of informality in manufacturing is more complex. For a discussion on informality in the Indian economy and the transition from informal to formal, see Sankaran (2022).

- Data from the Annual Survey of Industries for various years can be accessed here.

- The KLEMS database contains industry level time series data on capital (K), labour (L), energy (E), materials (M) and service (S) inputs, along with data on output and productivity. This estimate in the KLEMS database is based on the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- There are several studies which have found a positive effect of ICT on the productivity of informal sector enterprise in India (see, for example, Gupta and Kumar (2018)).

Further Reading

- Bhattacharjea, Aditya (2023), “Industrial policy in India since Independence”, Indian Economic Review.

- Goldar, B (2023), ‘Employment Growth in India’s Organized Manufacturing in the Post-GFC period’, SSRN Paper.

- Gupta, Mitali and Manik Kumar (2018), “Impact of ICT Usage on Productivity of Unorganised Manufacturing Enterprises in India”, Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 61: 411-25.

- Krishna, KL, B Goldar, DK Das, SC Aggarwal, AA Erumban and PC (2022), ‘India Productivity Report’, Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics. Available here.

- Nagaraj, R and R Kapoor (2022), ‘What is ‘formalization’ of the economy: India’s quest to shrink its informal sector’, The India Forum, 12 January.

- Sankaran, Kamala (2022), “Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy: The Need for a Multi-faceted Approach”, Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 65(3): 625-642.

- Unni, Jeemol (2018). “Formalization of the Informal Economy: Perspectives of Capital and Labour”, Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 61(1): 87-103. Available here.

01 March, 2023

01 March, 2023

Source: Author’s computations based on ASI data and India KLEMS database.

Source: Author’s computations based on ASI data and India KLEMS database.

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.