The steep increase in excise taxes on cigarettes in this year’s Union Budget is a welcome move. However, this column argues that unless more commonly consumed bidis are also taxed heavily, the public health objectives of tobacco taxation will go up in smoke.

The steep increase in excise taxes on cigarettes, especially those of shorter length (not exceeding 65 mm), in the 2014-15 Union Budget is indeed a victory for public health in India. To an extent, it is a success of health policy advocates and researchers in the country. Two recently concluded studies by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and the Public Health Foundation of India (PFHI) were instrumental in this regard. These studies provided the necessary evidence for the need to increase tax on tobacco products. The former reported that the total economic costs attributable to diseases related to tobacco use for persons aged 35-69 amounted to Rs. 1,045 billion (US$ 22.4 bn approx.) in 2011. However, in the same year, the total central excise revenue from all tobacco products amounted to Rs. 174 billion (US$ 3.73 bn approx.) only – 17% of the estimated economic costs. The PHFI study, on the other hand, found that cigarette and bidi excise tax can be increased by 370% and 100% of present levels respectively before tax revenues from these products would begin to decline. The study also estimated that such increases in taxes can reduce consumption of cigarettes and bidis by 54% and 40% respectively.

Cigarette taxation

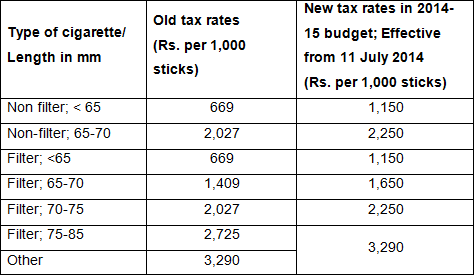

Table 1 below shows the increases in central excise tax on cigarettes in the Union Budget 2014-15.

Table 1. Central excise tax on cigarettes, Union Budget 2014-15

Source: Budget documents, Government of India

Source: Budget documents, Government of India Note: In India, taxes on cigarettes/ bidis are levied as tax per 1,000 sticks, not on the value of the product. The price per 1,000 sticks varies within a tier, but tax amount remains the same.

Another good measure in this year´s budget is the decision to merge the top two tiers of cigarettes into one for the purpose of taxation. This would help simplify the cigarette taxation structure to some extent. However, eliminating the tier structure altogether and taxing all cigarettes uniformly at the rates currently applied to the longest length of cigarettes would lead to greater benefits. Firstly, it would discourage customers from switching between tiers when taxes increase in certain segments. Secondly, it would reduce the practice of shortening the cigarettes by tobacco industry, as was done by ITC Ltd. (earlier known as Imperial Tobacco Company of India Ltd.) recently - the company shortened its low-priced cigarettes by five millimeters, only to escape higher taxation in the upper tiers. A single tax on cigarettes regardless of length would result in a much simplified tax structure that is easier to administer.

But what about bidis?

Noticeably, the highest increase in tax (72%) is for the bottom tier (cigarettes less than 65 mm in length). This is indeed a great step as this is a segment that has seen more than three times growth in sales in 2013-14, accounting for 16% of the total volume of sales of the tobacco industry as compared to 4% in 2012-13 (The Tobacco Institute). However, tax on bidis continues to be a meagre 7%, on average, as compared to 43% for cigarettes. The tax per stick is 1.2 paise for handmade bidis (constituting 98% of all bidis produced in India) and 3 paise for machine-made bidis. In contrast, the lowest-taxed cigarettes now attract a tax of Rs. 1.15 per stick (Jha et al. 2011). These taxes are far less than the recommended 70% by the World Health Organization (WHO). Even though bidis and cigarettes are traditionally consumed by distinct group of consumers who may not substitute one for the other, one can expect substitution between bidis and lower-tier of cigarettes following the tax increase.

Bidis are as harmful as cigarettes and command a market share of 85% of smoked tobacco products in India, making them the most popular form of smoking tobacco in the country (Nandi et al. 2014). There is no justifiable reason why they should not be treated similar to cigarettes for the purpose of taxation. Research from both high- and low-income countries has demonstrated that tobacco tax and price increases are the most effective tools to reduce tobacco use; they promote cessation among current users, deter young people from taking up tobacco use, and reduce quantity of consumption of continuing users (Jha et al. 2014, Chaloupka 2014). It is important that the Indian government takes cognisance of this and uses taxation as an effective tool to curtail consumption of bidis as well. Hence, the omission of bidis from the ambit of increased taxation in the present budget is a serious one in this regard.

Given that we follow a quantity tax on both bidis and cigarettes, the distribution of tax revenue between these products should be in the same proportion as their sales. However, the existing tobacco tax revenue is highly skewed with nearly 85% of the tobacco tax revenue coming from cigarettes alone, which account for only 15% of the tobacco consumption in India (John et al. 2010). Exempting bidis from regular tax increases is tantamount to leaving roughly 85% of the smokers outside of the tax, and substantially narrows the tobacco tax base of the nation. Bidi industry´s economic contribution is small relative to the disproportionately large public health damage from bidi smoking (Nandi et al. 2014). Apparently, political considerations rather than public health concerns are at the forefront while devising tax policies for bidis. Arguments such as regressivity of bidi taxes, threatened livelihood of bidi rollers etc. do not have any public health rationale and are only acting as impediments in the way of increasing bidi taxes. Given that bidi consumption is price sensitive with price elasticity (responsiveness of the demand for bidis to a change in the price of bidis) close to one1 (John et al. 2010), higher taxes on bidis can only help the poor in terms of better returns from their improved health and income resulting from lower consumption. Policies such as tax exemptions for bidi manufacturers producing less than two million bidis in a year (with no such exemption exists for cigarettes), and differential tax rates for handmade and machine-made bidis, subvert the public health goal of tobacco taxation in India by incentivising bidi makers to engage in tax evasive practices.

What the government should do

With one million deaths in India a year due to tobacco use (Jha et al. 2008), it is time to look at tobacco taxation policy through the lens of public health, rather than revenue generation. With tobacco becoming more affordable over the years, what is required is a commitment to increase specific tax rates on tobacco annually at a rate that is greater than inflation and per capita income growth. Besides bringing excise tax on all tobacco products to at least 70% of the retail price as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), it is also imperative that the respective state governments impose a uniform Value Added Tax (VAT) on tobacco products with the sole purpose of discouraging inter-state smuggling.

The enormous costs to the nation on account of tobacco use and the associated diseases and deaths eclipse any benefits or tax revenue earned from tobacco. The objective of tobacco taxation should be clearly redefined as a tool to safeguard public health. After all, we don´t want to make the future growth and development of a growing nation contingent on ‘sin taxes’. In any case, taxes from tobacco contribute only around 2% of the total gross tax revenues in a year and that is an amount for which a responsible government should be able to find alternative sources.

Notes:

- This has been calculated based on data from household consumption surveys of the National Sample Survey Organization of India (NSSO).

Further Reading

- Chaloupka, FJ (2014), "Taxes, prices and illicit trade: the need for sound evidence", Tobacco Control, 23(e1):e1-2. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051739

- Government of India (2014), ´Union Budget 2014-15: Customs and Central Excise Notifications´, Research Unit, Department of Revenue Tax, Ministry of Finance, New Delhi. Accessed on 11 July 2014.

- Gupta, PC and S Asma (2008), ´Bidi Smoking and Public Health´, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi.

- Jha P and R Peto (2014), "Global Effects of Smoking, of Quitting, and of Taxing Tobacco", New England Journal of Medicine, 370(1):60-68.

- Jha, P, E Guindon, RA Joseph, A Nandi, RM John, K Rao, FJ Chaloupka, J Kaur, PC Gupta, and MG Rao (2011), “A Rational Taxation System of Bidis and Cigarettes to Reduce Smoking Deaths in India.” Economic and Political Weekly, XLVI(42): 44–51.

- John, RM, RK Rao, MG Rao, J Moore, RS Deshpande, J Sengupta, S Selvaraj, FJ Chaloupka, P Jha (2010), ‘The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Taxation in India’, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris.

- John, RM (2008), "Price Elasticity Estimates for Tobacco in India", Health Policy Plan, 23(3):200-209.

- John, RM, SK Rout, BR Kumar and M Arora (2014), ´Economic Burden of Tobacco Related Diseases in India´, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi.

- Nandi, A, A Ashok, GE Guindon, FJ Chaloupka, and P Jha (2014), “Estimates of the Economic Contributions of the Bidi Manufacturing Industry in India”, Tobacco Control, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051404. [Epub ahead of print]

- Selvaraj, S, S Srivastava, SK Rout, M Arora and A Yadav (2014), ´Raise Tobacco Taxes to Prevent Disease and Save Lives´, Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi.

09 December, 2014

09 December, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.