Identifying whether newspaper editors focus on what is ‘newsworthy’ or what is ‘trendy’ when choosing stories is important for the design of media regulation. This column shows how the popularity of an article, reflected by online clicks, influences the coverage of the story. However, this strategy operates differently for ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ news and hence, does not lead to a general decline of the quality of content.

The terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo in Paris in January 2015 dominated the news all around the world for several days. Around the same time, the Boko Haram killed 2,000 people in a Nigerian village but it hardly made the news anywhere. A major factor, among others, which came to the fore for why Boko Haram didn´t get similar news coverage was that people around the world were not interested enough in the events happening in Nigeria. In other words, there was a lack of demand on the part of the readers for the story.

In recent research, we analyse the impact of newspapers´ need to maximise readership to increase advertising revenue, on editorial coverage decisions in the context of online news (Sen and Yildirim 2015). Without news being available online, circulation rates would provide information about the popularity of a newspaper as a whole but could never indicate how well inpidual articles were faring. Online editions of newspapers enable editors to track and respond, in real time, to the number of clicks at the level of an article or URL1. Yet, reputable news outlets such as The New York Times claim that their editors do not take decisions based on web statistics. Even newer news outlets such as the Verge and Vox.com prevent their journalists from accessing any real-time demand data so that they focus on what is ‘important´ rather than what is ‘trendy´.

Exploring whether decisions of news editors systematically cater to the preferences of the readers is important for a few reasons. There is theoretical work which shows that selective coverage of stories due to their sensational appeal by a newspaper can distort the beliefs of readers and make them take sub-optimal actions, than if they were perfectly informed (Best 2009). For example, there is evidence which shows that people switch to road travel in the aftermath of airline crashes and their extensive coverage by the media even though fundamentally air travel is much safer than travelling by road. Further, identifying whether news stories are chosen because of demand-side (or supply-side) reasons is important for the design of media regulation. The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), for example, has ignored demand-side incentives while proposing regulations for media ownership, assuming a supply-side association between ownership of the news outlet and the viewpoint expressed it. While that might sometimes be true, if a newspaper systematically writes additional articles on a story just because of its sensational appeal then there would be additional regulatory implications2 .

Methodology

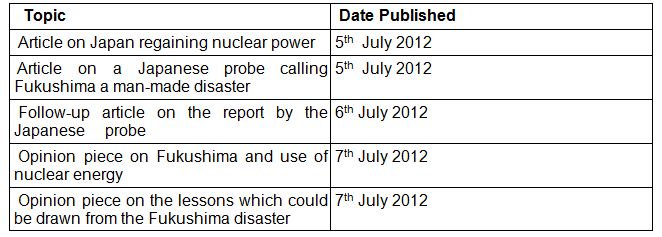

Our study aims to analyse the causal impact of story popularity on editorial decisions. This is not a trivial exercise due to a few reasons. First, we are interested in disaggregated editorial decisions; this requires data at the article level. To this end, we were able to acquire proprietary information from a leading English language Indian national daily newspaper on the clicks received by all articles published by it in the year 2012. We combined this with publicly available data collected by ‘crawling’ the news website. In particular, we use an automated script to scrape the news site to collect data on the text of each article along with its headline, whether it had a picture on the page, the time and date the article was published, as well as the source of the article. To construct stories, our unit of analysis, we identify the similarities between news articles based on proper nouns occurring in the articles and classify sufficiently similar articles into clusters or stories using methods borrowed from the computer science literature. A follow-up story on the Fukushima disaster, which took place in 2011, is what a typical story looks like in our dataset:

Table 1. A typical ‘story’ in the dataset

Secondly, clicks and coverage could be correlated if a story is in fact both newsworthy/ important and of interest to readers, which would drive both more clicks and coverage. To ensure that our estimates don´t reflect mere correlations, we focus on two exogenous (external) shocks to reader clicks to establish a causal relationship between clicks and coverage: days with rain and the level of electricity shortage. On rainy days, readers are constrained in the number of activities they can carry out and may choose to remain indoors, which can increase the time they spend online reading news. On days with power shortages, inpiduals´ ability to connect to the internet is limited, and so is their ability to visit the news site. Under the assumption that the newsworthiness of stories is not affected by rain or power outages, we essentially compare how editors respond to the clicks received by the average story first published on a rainy day versus the average story published on a day when it does not rain (and similarly for power outages).

We then move on analyse the impact of clicks-based editorial coverage on the ‘quality´ or nature of information provided to readers. We address whether the editor treats the clicks received by different types of news stories, such as political versus a sports story, the same. In essence, we try to see if there is ‘dumbing down´ of content because of popularity driven strategies which is the widely held belief. We group stories in the National, International, Business and Opinion sections as ‘hard´ news while stories in the Entertainment, Technology, Lifestyle and Sports sections are grouped as ‘soft´ news and then we re-estimate the model. Further, we adopt a different approach to this issue by exploiting variation in clicks received by soft news stories relative to hard news to see whether that crowds out hard news articles. In particular, we focus on Indian cricket matches during the year, as big exogenous soft news events, to see if on match days, hard news is crowded out.

Results

Our study provides a few key insights about the impact of online information on editorial policy. First, we find that stories whose first articles are published on rainy days get 5% more clicks, while power outages are negatively correlated with the number of clicks. Using this exogenous (external) variation in clicks, we find that an increase in the views of the first article of a story significantly increases the coverage provided by the newspaper on the same story. We find that a 10% increase in the clicks of the first article of a story increases its coverage, in terms of the number of articles, by 3%. In essence, we can convert the number of clicks into advertising revenue and arrive at a price for writing an additional article on the same topic.

Second, estimating the model by splitting the sample into hard and soft news stories, we show that clicks have a positive and significant impact on the coverage only for hard news. The newspaper gives additional coverage only in response to the clicks received by hard news and not to those received by soft news. Complementing this result, we find that the proportion of clicks to hard news on days when India plays a cricket match is lower by about 5%. This reduction in clicks for hard news, however, does not change the proportion of hard news articles published on those particular days. Furthermore, days on which news on corruption scandals breaks out, we see that hard news clicks increase by 4% which leads to an increase in the proportion of hard news articles by over 2% on those days. We view this as a positive result that should allay some concerns about the dumbing down of content online, at least at first pass.

Finally, when editors´ decisions are guided by the clicks articles receive, stories may be allocated resources due to events such as rain and power outages, which are arguably orthogonal to the newsworthiness or importance of stories and may crowd out other newsworthy stories. Quantifying editorial misinterpretation due to the additional clicks on rainy days is not straightforward since it could be rational for the editor to provide more coverage to stories which get a larger number of clicks if readers simply like to read more on topics they have already read. However, if this was true, we should observe such an editorial strategy in any other situation where there is an exogenous increase in readers´ attention which the newspaper is aware of. We find that national holidays and weekends, lead to an increase in clicks of a magnitude similar to rainy days but do not lead to an increase in coverage, suggesting that editors are aware of these exogenous increases in reader attention. We find that the average rainy day story is given up to 5% additional coverage relative to weekends and 2.5% relative to national holidays. Moreover, as an additional check, we find that the clicks received by the second article of a story whose first article was published on a rainy day are lower by 4-6% relative to the views received by the second article of a story whose first article was not published on a rainy day.

Summing up

Our paper has potential implications for both firm strategy and media regulation. We highlight how popularity shapes editorial decisions, independent of their political preferences, while a large majority of studies in the economics literature (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010, Prat and Stromberg 2013) focus on the political aspects of media coverage. Political preferences alone, however, fall short of explaining how day-to-day editorial decisions are made. Our results also point to an asymmetric strategy across different types of news stories (hard vs. soft), which goes against the general perception about the decline in the quality of news available online and ‘dumbing down’ of content based on demand/ popularity. Finally, our result on editors misreading the source of the clicks also speaks to a real concern about newspapers being overwhelmed with digital information and the fact that they are unable to handle and interpret ‘big data´ which would adversely affect information provision for the readers as well as the newspapers´ profits.

Notes:

- URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator. It is a reference or address to a resource on the internet.

- This could point towards the need for additional regulation on content; for example, in the case of air travel news, regulation should ensure that news coverage reflects underlying risk statistics.

Further Reading

- Sen, A and P Yildirim (2015), ‘Clicks and Editorial Decisions: How does Popularity Shape Online News Coverage?’, Mimeo.

- Best, M (2009), ‘If It Bleeds It Leads: Sensational Reporting, Imperfect Inference and Crime Policy’, Mimeo.

- Gentzkow, Matthew and Jesse M Shapiro, (2010), "What Drives Media Slant? Evidence From U.S. Daily Newspapers”, Econometrica, Econometric Society, vol. 78(1), pages 35-71.

- Prat, A and D Stromberg (2013), ‘The Political Economy of the Mass Media’, in Acemoglu, D, M Arellano and E Dekel (eds.), Advances in Economics and Econometrics: Theory and applications, Tenth World Congress, Cambridge University Press.

18 May, 2015

18 May, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.