Although recent research on inequality shows that upper castes have the highest levels of material well-being, there is a wide variation in caste inequality across India. Measuring three forms of caste inequality – outcome (income), opportunity (literacy), and status (inter-caste marriage, untouchability, and crime) – this article finds that state rankings depend on the indicator considered. There is, however, a clear north-south divide.

The common adage, “in India, people do not cast their votes, they vote their caste”, is not completely inaccurate. Caste overwhelming determines politics at all levels (Chandra 2004). Political thinkers like Ambedkar, Lohia, and Periyar – that most contemporary lower-caste parties draw upon – believed that caste, more than class, was the basis of Indian society. Recent research on inequality supports their claim – upper castes have the highest levels of land ownership, consumption expenditure, and income, followed by the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and Scheduled Caste (SCs) (Dubey and Desai 2011, Bharti 2019). But at the same time, not all states are equally unequal. The long history of social movements in South India has been credited with reducing social hierarchy over time (Ahuja 2019). Some scholars have also argued that hill communities in the Himalayan states tend to more interdependent in order to survive their harsh terrain, which in turn makes them more egalitarian (Das et al. 2015). But how do Indian states compare in terms of caste inequality? And how should we even measure inequality in the first place?

Measuring caste inequality

I begin by drawing on political theory. Equality has been conceptualised in three ways: (i) equality of outcomes, (ii) equality of opportunity, and (iii) equality in social status. The most basic understanding of equality is based on an individual’s material condition. Income and wealth can generally buy a decent quality of life. Equality of outcomes can be interpreted as differences in these outcomes across groups. Equality of opportunity alludes to the role of the state and society in providing a somewhat level playing field. One may not be born into a wealthy family, but certain public services, especially education and healthcare, should be accessible to everyone. In the field of development, the principles of equality of opportunity motivated the creation of the Human Development Index (HDI) by the United Nations. HDI measures well-being in terms of three factors – income, health, and education. Equality of status relates to the distribution of ‘honour’, respect, or prestige across groups. Rather than material deprivation or lack of access to public services that the first two concepts capture, status inequality manifests itself through discrimination and humiliation (Deshpande 2019). Status is particularly relevant in India given the legacy of the caste system. It is not surprising that lower-caste mobilisation has focussed on fighting the indignity of caste hierarchy (Jensenius 2017).

In new research, I operationalise these concepts by measuring the difference between SCs and other groups, relying on publicly available datasets (Chakrabarti 2021). I measure inequality in outcomes through income data from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS). The measure, “Between-Group Inequality (BGI)”, corresponds to the correlation between caste and income. To measure inequality in opportunity, I examine the difference in literacy rates between the general population and SCs, relying on Census data. The concept of status inequality is more difficult to operationalise. Ideally, a measure of status should be able to capture the strength of social hierarchy that is independent of the economic and political power of the groups. Caste is maintained through norms of endogamy1 and segregation. The rate of inter-caste marriage, as recently as 2011, was less than 6% (Chaudhuri et al. 2018). Though the Constitution criminalised untouchability, some forms of untouchability continue to be practiced across the country (Thorat and Joshi 2020). In more extreme cases, caste hierarchy is enforced through violence. I measure caste-based status inequality in three ways: the prevalence of inter-caste marriage, practice of untouchability, and caste-based violence2. The first two measures are based on IHDS data. I use data on serious crimes against SCs from the National Crime Records Bureau to measure caste-based violence.

Ranking states on the basis of caste inequality

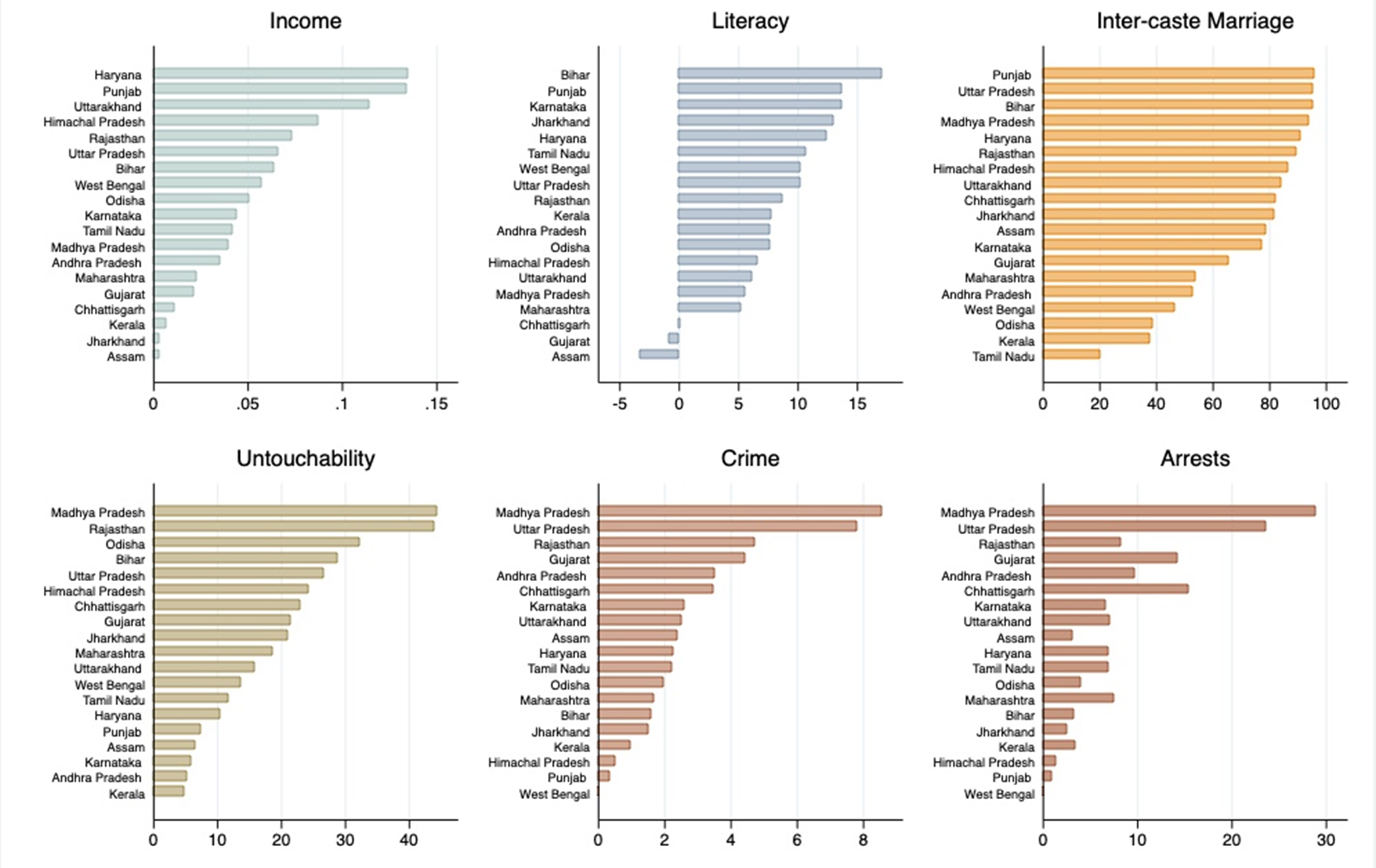

So how do Indian states rank in terms of caste-based inequality? The answer, to an extent, depends on what we are measuring. Surprisingly, the five measures of inequality are not highly correlated with each other (Table 1). The measures on status inequality present somewhat similar patterns, but overall, there is a clear divergence between measures of material well-being and social relations. Haryana and Punjab have the highest levels of inequality in income, literacy, and inter-caste marriage but rank low on the practice of untouchability and caste-based violence. Similarly, caste-based violence in Himachal Pradesh is low, but contrary to our understanding of hill societies, they have one of the highest levels of income-based inequality and untouchability. Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh represent the opposite pattern – SCs in these states experience exclusion and violence even while inequality in income and literacy is relatively low. Why might this be?

Table 1. Correlation matrix: Measures of caste inequality

|

Income |

Literacy |

Inter-caste marriage |

Untouchability |

Murder |

|

|

Income |

1.00 |

||||

|

Literacy |

-0.22 |

1.00 |

|||

|

Inter-caste marriage |

-0.10 |

-0.29 |

1.00 |

||

|

Untouchability |

0.18 |

-0.26 |

0.72 |

1.00 |

|

|

Murder |

-0.13 |

-0.22 |

0.56 |

0.49 |

1.00 |

Samuel Huntington had famously argued that conflict often accompanies social transformation (Huntington 1968). A recent study finds that violent crime against SCs is the highest in districts where the difference in the standard of living between SCs and upper castes has declined the most (Sharma 2015). Violence against SCs may hence reflect a backlash against lower-caste empowerment. Paradoxically, caste-based violence may be low in one of the two extreme contexts – when social relations are relatively egalitarian, as reflected in South India, or when the social order is so unequal that lower castes are unable to question their position in the hierarchy, as possibly reflected in some north Indian states. Data on crime are also likely to be affected by reporting bias. With the exception of serious crimes like murder, SC victims may be hesitant to report crimes, or the police may be reluctant to file reports due to pressure from local elites. The rate of SC murders in Kerala is low, but it has one of the highest levels of SC rapes. The data on rapes may in fact reflect lower reporting bias in gender-related crimes. Hence rather than indicating caste inequality, these numbers may in fact suggest relatively equal gender and caste relations, and a responsive State.. Rajasthan, in contrast, reports high levels of SC violence but the state arrests fewer people for these crimes compared to other states. It also ranks at the top of most measures of caste-based inequality.

Figure 1. Ranking states on different forms of caste inequality

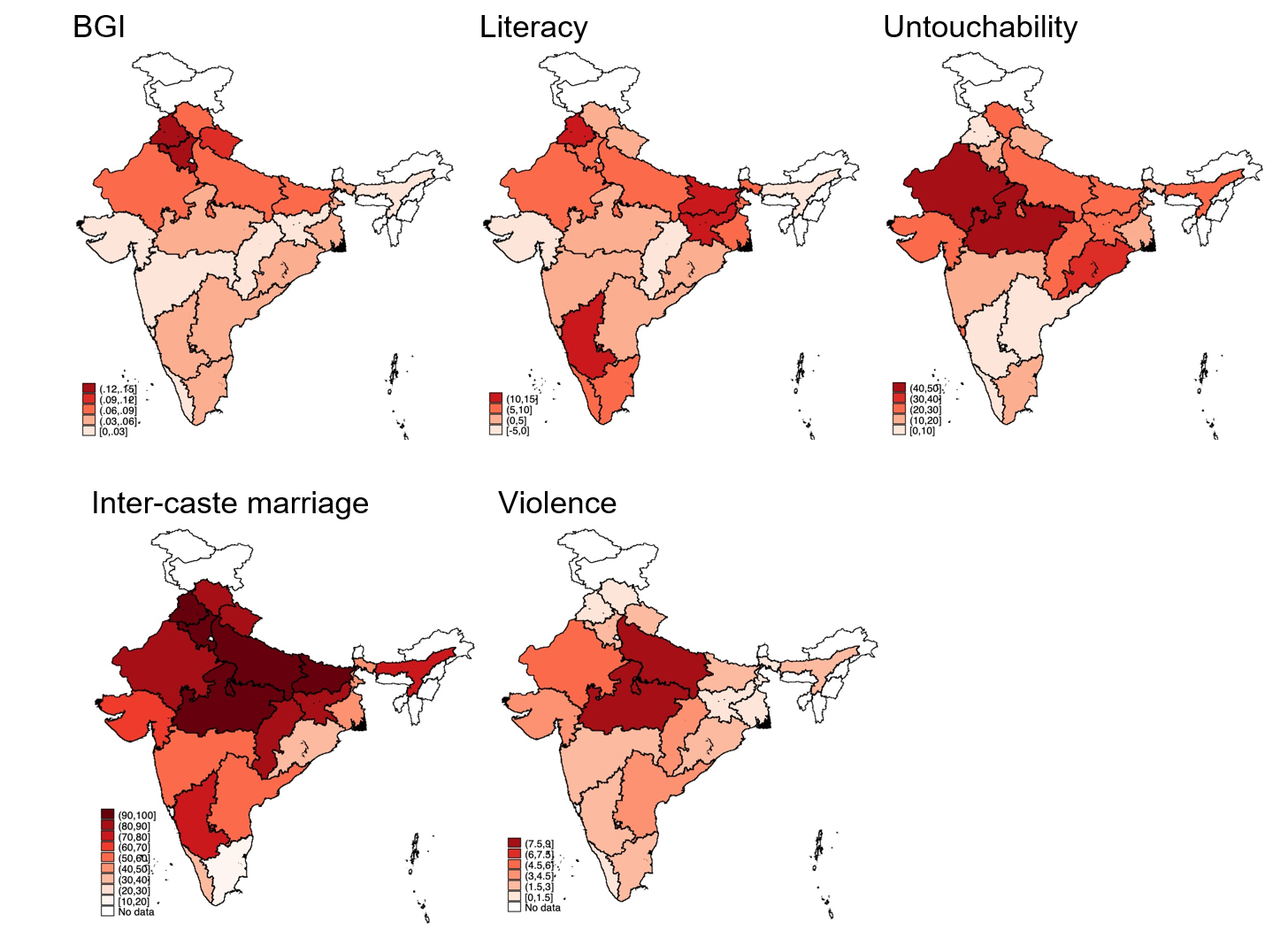

Notwithstanding the contrasting patterns in forms of inequality, the north-south divide stands out in the state rankings (Figure 2). The southern states are indeed more equal when it comes to social relations. The northern states of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar have high levels of inequality on most measures. Assam and Kerala, in contrast, fare better than most states. Kerala’s exceptional performance in development, and egalitarian social structure has been widely documented (Drèze and Sen 2013). Caste politics in Assam has unfortunately attracted less attention, but these findings seem consistent with existing research. It is the only state where the share of non-agricultural workers employed in SC-owned firms is higher than their population share (Iyer et al. 2013). Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and West Bengal generally have low ranks in many measures of caste inequality.

Figure 2. Mapping states on forms of caste Inequality

Discussion

My findings also raise important questions about the reliability and interpretation of the available sources of data. Data on literacy and crime is based on official statistics. As one of the few sources of longitudinal data, it allows us track inequality over time. But as discussed earlier, results based on crime data may reflect reporting bias. Measures based on outcomes like income and wealth, literacy, incidence of inter-caste marriage are generally less likely to be affected by reporting bias. While literacy figures from the population census are reliable, as school enrolment and literacy rates in India increase, the difference in literacy rates between the overall population and SCs will become less meaningful over time. Data on years of educational attainment will produce better measures in the years to come. Most importantly, while identity-based discrimination is a defining feature of caste, currently only two nationally representative surveys have collected data on caste-based exclusion – IHDS and Rural Economic and Demographic Survey (REDS). Measures on income inequality, inter-caste marriage, and untouchability presented here are based on the one round of the IHDS survey. Findings from other sources will be useful to corroborate these results and explore changes over time. As several public intellectuals have recently argued, the caste census will allow us to better understand how resources and social opportunity are distributed across social groups and can hence help us design more effective public policies. But what is clear is that in order to understand the complexity of caste-based inequality, especially with greater urbanisation and growth in non- agricultural sectors, we need to examine both material and non-material sources of exclusion.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- Endogamy refers to the practice of marrying within one’s own caste.

- I use the following question in the IHDS survey that was asked only to SC respondents: “In your household have some members experienced untouchability in the last 5 years?”.

Further Reading

- Ahuja, A (2019), Mobilizing the Marginalized: Ethnic Parties Without Ethnic Movements, Oxford University Press.

- Bharati, NK (2019), ‘Wealth inequality, class, and caste in India: 1961-2012’, Ideas for India, 28 June.

- Chakrabarti, P (2020), ‘The Politics of Dignity: How Status Inequality shaped Redistributive Politics in India', Working Paper.

- Chandra, K (2004), Why Ethnic Parties Succeed: Patronage and Ethnic Head Counts in India, Cambridge University Press.

- Chaudhuri, AR, T Ray and K Sahai (2018), ‘Whose education matters? An analysis of inter-caste marriages in India’, Ideas for India, 30 November.

- Das, MB, S Kapoor-Mehta, EO Tas and I Zumbyte (2015), ‘Scaling the Heights: Social Inclusion and Sustainable Development in Himachal Pradesh’, World Bank Working Paper.

- Desai, Sonalde and Amaresh Dubey (2011), “Caste in 21st Century India: Competing Narratives”, Economic and Political Weekly, 46(11): 40-49.

- Deshpande, A (2017), The Grammar of Caste: Economic Discrimination in Contemporary India, Oxford University Press.

- Drèze, J and A Sen (2013), An Uncertain Glory, Princeton University Press.

- Huntington, S (1968), Political Order in Changing Societies, Yale University Press.

- Iyer, L, T Khanna and A Varshney (2013), ‘Caste and entrepreneurship in India’, Ideas for India, 26 August.

- Jensenius, F (2017), Social Justice Through Inclusion: The Consequences of Electoral Quotas in India, Oxford University Press.

- Mosse, David (2018), “Caste and development: Contemporary perspectives on a structure of discrimination and advantage”, World Development, 110: 422-436. Available here.

- Sharma, Smiti (2015), “Caste-based crimes and economic status: Evidence from India”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(1): 204-226. Available here.

- Thorat, Amit and Omkar Joshi (2020), “The Continuing Practice of Untouchability in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 55(2): 36-45.

13 September, 2021

13 September, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.