The rate of inter-caste marriages in India was as low as 5.82% in 2011 and there has been no upward trend over the past four decades. This article examines the relationship between inter-caste marriages and education in India. It finds that education of spouses has no effect on the likelihood of the marriage being inter-caste; rather it is the education of the husband’s mother that plays a role. It highlights the importance of recognising the institution of ‘arranged’ marriage in any analysis of Indian marriage markets.

Endogamy is to caste what caste is to the Indian society. The practice of caste endogamy – marrying within the boundaries of one’s own caste – is not only central to the institution of caste but is also one of the most resilient caste-based practices. The rate of inter-caste marriages, even as recently as 2011, was merely 5.82% and there has been no upward trend over the past four decades1. In recent research (Ray et al. 2017), we study the relationship between caste endogamy and education in India.

The existing related literature, which is mostly based in a developed country context, finds mixed results on the relationship between ethnic endogamy and education (Qian 1997, Fryer 2007, Qian and Lichter 2001, Hwang et al. 1995, Gullickson 2006). Such a study had not yet been undertaken at a national level in India, mainly due to paucity of relevant data. The task is made more difficult by two additional issues. Firstly, the definition of caste is very fluid and unclear. This poses a serious credibility threat to any definition of an ‘inter-caste’ marriage that one may use because caste affiliations and caste distances are often unclear. Secondly, marriage markets in India work very differently as compared to the Western countries (Banerjee et al. 2013). A majority of marriages in India are arranged by the parents, and hence the degree to which education of the marital partners affect the caste nature of the match is an open question.

Data

We use data from the latest round of the IHDS-II (India Human Development Survey) conducted in 2011-12. The IHDS is a nationally representative household panel survey which has detailed socioeconomic- and human development related questions for a household as a whole, for young children in the household, and for one married woman in the age group of 15-49 years in each household called the ‘eligible woman'2.

We address the first concern mentioned above by using the following question from the IHDS: “Is your husband’s family the same caste as your natal family?” Hence, instead of defining an inter-caste marriage ourselves, we follow what the survey respondent thinks about her marriage as that would be closer to her own lived reality. Secondly, to take into account the nature of marriage markets in India, we focus not only on the education of the spouses but also the education of the parents on both sides of the match.

Setting the context

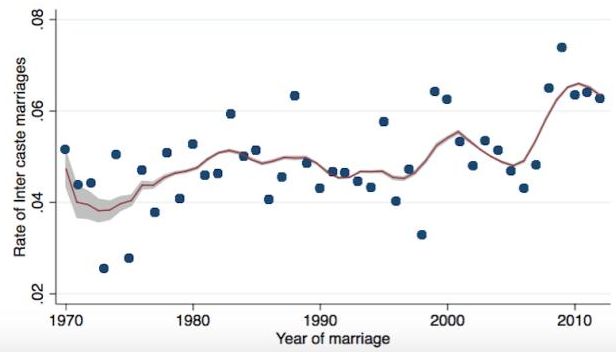

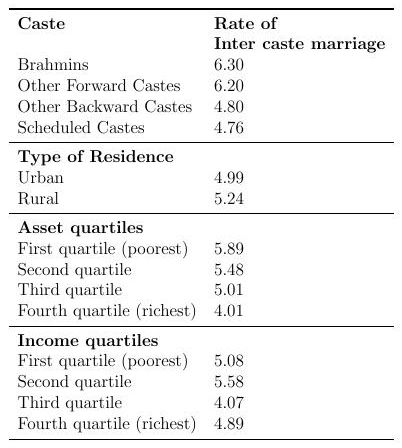

Figure 1 plots the rate of inter-caste marriages by the year of marriage. The rate hovers around 5% from 1970 to 2012 and no clear upward trend is visible. Table 1 shows the rate of inter-caste marriages by various characteristics of the household of the husband. The only statistically significant differences in the rates are between that of OFCs (Other Forward Castes) and OBCs (Other Backward Classes), and OFCs and SCs (Scheduled Castes)3. The second panel of the table shows that, contrary to common wisdom, the rate of inter-caste marriages does not differ statistically between urban and rural areas.

The next two panels show the rate of inter-caste marriages by asset- and annual per capita income quartiles of the households respectively. For both these measures, the rate goes down as we move up the asset distribution (poorest to the richest).

Figure 1. Trend in the rate of inter-caste marriages: 1970-2012

Data source: IHDS II.

Table 1. Rate of inter-caste marriages by household characteristics

Decision-making at the time of marriage

The arranged marriage set-up of the Indian marriage market is clearly visible in our dataset.

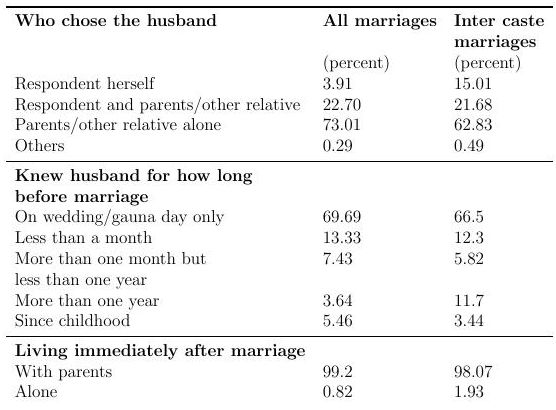

The first panel of Table 2 shows that of all marriages, a striking 73% of women say that parents (or other relatives) chose their husbands and almost 70% of them met their husbands only on the day of their wedding/gauna4. Even within the set of only inter-caste marriages, almost 63% are arranged by parents/other relatives only. Also notable is the observation that among all inter-caste marriages, an overwhelming 98.07% of couples lived with their parents immediately after marriage (last panel of Table 2). These observations lend reasonable amount of support to the idea that the effect of parental attributes should be relevant in any analysis of marriages in India, along with that of individual attributes.

Table 2. Decision-making at the time of marriage

Inter-caste marriages and education

Our first result is that the level of education of the individuals themselves (husband or wife) does not have any association with the likelihood of their marriage being an inter-caste one6. This result stands in sharp contrast to the existing literature focused on marriage markets in developed countries which largely find own education to have an effect on inter-group marriage.

Next we check if the statistical insignificance of own education is driven by specific mechanisms explored in the literature. Furtado (2012) describes two channels through which education might influence the probability of exogamy which can potentially work in opposite directions. While the “cultural adaptability” effect can increase the incidence of intermarriage if education makes members of different ethnic groups more adaptable to the culture of each other, the “assortative matching” effect may have a negative influence on intermarriages of a group with education level above the average education level of the relevant population. We check whether the statistical insignificance of individuals’ own education is being driven by these effects cancelling each other out. Our results are robust to the consideration of these different channels.

We also check if the statistical insignificance of own education reflects evidence in support of the ‘status Exchange’ theory (Gullickson 2006, Rosenfeld 2005, Kalmijn 1998, Fu and Heaton 2008). In any inter-caste marriage, the upper-caste individual will typically be able to exchange their caste status for a higher level of education of a spouse from a lower caste as compared to the level of education of the spouse they would be matched to in an intra-caste marriage. This heterogeneity in the direction of the relationship between education and intermarriage for different castes could lead to a null relationship between education and inter-caste marriages. We check against this possibility, and here too, our results reaffirm our original findings.

Role of parents?

To account for the practice of arranged marriages in India, we add the education level of the parents of both the spouses to our set of explanatory variables. Here we find that the education of the husband’s mother has a positive and statistically significant effect. An increase in years of education of the husband’s mother by 10 years would lead to an increase in the probability of inter-caste marriage by 1.86 percentage points, which is equivalent to approximately 36% of the sample mean (average)7.

Discussion and conclusion

The second part of our findings on the role of parents is nuanced in two ways. First, only the education of the husband’s mother predicts inter-caste marriage, but not that of his father. Second, education of the wife’s parents is not associated with the likelihood of an inter-caste marriage. We try to understand the first aspect as follows. A growing body of literature finds evidence that a more educated woman has an increased bargaining power and decision-making power in a household (for example, Beegle et al. 2001, Doss 2013, Thomas 1994). It is also well documented, especially in the context of developing countries, that a mother is more responsive to the needs of her child, as compared to the father (Duflo 2000, Duflo and Udry 2004, Friedberg and Webb 2006). Given that we are looking at marriages ex-post, they must be revealed preferred to be the optimal matches from all the potential matches available. An intra-caste match could, then, be a constrained optimum if the father, driven by social norms and being less sensitive to the best outcome for the son, insists on the intra-caste constraint. An inter-caste marriage is more likely to occur when an educated mother can overcome this constraint and implement the best outcome for the son, empowered by her increased bargaining and decision-making authority in the family.

One simple explanation of the second aspect could be that in Indian marriages, the groom’s family has more bargaining power. Another possible explanation is that education may not have enough mitigating effect on the stigma of an inter-caste marriage for the bride’s family which bears these costs disproportionately.

To conclude, our analysis highlights the importance of recognising the institution of arranged marriage in any analysis of Indian marriage markets. Taken together, the two aspects of our results indicate that once the arranged marriage set-up is recognised, one can make sense of the result that own education has no effect on the decision of one’s own marriage, rather it is the parents’ education that matters.

Notes:

- This is based on the authors’ calculations using IHDS-II (India Human Development Survey) data.

- It includes women who are currently married as well as those who are widowed.

- Here the abbreviations stand for the administrative caste categories in India.

- Gauna is associated with the custom of child marriage in India. The gauna ceremony takes place several years after marriage. Before the ceremony, the bride stays at her natal home. Conjugal life begins only after gauna.

- This result is robust to the addition of a host of control variables (variables that are not changed throughout an experiment, because their unchanging state allows relationship between other variables being tested to be better understood) and fixed effects (variables that are constant across individuals, like sex or ethnicity, and do not change or change at a constant rate over time).

- The result holds after variations in the sample, addition to a number of controls and fixed effects and to omitted variable bias (Oster 2017). Omitted variable bias occurs when a statistical model leaves out one or more relevant variables.

Further Reading

- Banerjee, Abhijit, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune (2013), “Marry for what? Caste and mate selection in modern India”, American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 5(2): 33-72. Available here.

- Beegle, Kathleen, Elizabeth Frankenberg and Duncan Thomas (2001), “Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal and delivery care in Indonesia”, Studies in Family Planning, 32(2): 130-146.

- Doss, Cheryl (2013), “Intra household bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries”, The World Bank Research Observer, 28(1): 52-78.

- Duflo, E (2000), ‘Grandmothers and granddaughters: the effects of old age pension on child health in South Africa’, Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Duflo, E and C Udry (2004), ‘Intra household resource allocation in Cote d’Ivoire: Social norms, separate accounts and consumption choices’, Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Friedberg, L and A Webb (2006), Determinants and consequences of bargaining power in households, Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Fryer, Roland G (2007), “Guess who’s been coming to dinner? Trends in interracial marriage over the 20th century”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2): 71-90.

- Fu, Xuanning and Tim B Heaton (2008), “Racial and educational homogamy: 1980 to 2000”, Sociological Perspectives, 51(4): 735-758.

- Furtado, Delia (2012), “Human capital and interethnic marriage decisions”, Economic Inquiry, 50(1): 82-93.

- Gullickson, Aaron (2006), “Education and black-white interracial marriage”, Demography, 43(4): 673-689.

- Hwang, Sean‐Shong, Rogelio Saenz and Benigno E Aguirre (1994), “Structural and individual determinants of out marriage among Chinese-, Filipino-, and Japanese-Americans in California”, Sociological Inquiry, 64(4): 396-414.

- Kalmijn, Matthijs (1998), “Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends”, Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1): 395-421.

- Oster, Emily (2017), “Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 1-18.

- Qian, Z (1997), “Breaking the racial barriers: Variations in interracial marriage between 1980 and 1990”, Demography, 34(2): 263-276.

- Qian, Zhenchao and Daniel T Lichter (2001), “Measuring marital assimilation: Intermarriage among natives and immigrants”, Social Science Research, 30(2): 289-312.

- Ray, T, A Roy Chaudhuri and K Sahai (2017), ‘Whose Education Matters? An Analysis of Intercaste Marriage in India’, Working paper.

- Rosenfeld, Michael J (2005), “A critique of exchange theory in mate selection”, American Journal of Sociology, 110(5): 1284-1325. Available here.

- Thomas, Duncan (1994), “Like father, like son; like mother, like daughter: Parental resources and child height”, Journal of Human Resources, 29(4): 950-988.

30 November, 2018

30 November, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.