How has over a decade of rapid and programmatic policy reform in Bihar affected voters? Based on a household survey comparing political attitudes of residents on either side of the Bihar-Jharkhand border, this column shows that Bihar’s policy reforms have raised voters’ expectations, but have not yet produced a fundamental change in their willingness to vote against clientelist politicians.

Crucial to India’s future is whether voters are vulnerable and dependent clients manipulated by politicians, or active and demanding citizens holding politicians to account. Prior to 2005, voters in Bihar fell overwhelmingly into the first category, facing a collapsing dysfunctional State and pressured to support violent, clientelist politicians. Trapped into voting for exploitative leaders to access even the most basic public services, accountability and policy reform was exceptionally weak.

But since 2005, under Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, Bihar has experienced extensive policy reform that has limited the scope for clientelism, extended the functioning of the State apparatus, and improved the economic condition of poor voters. While the welfare effects of these policies have been studied (for example, see here, here and here), their potential to reshape the fundamental rules of politics in Bihar has not. In a recent study, I seek to understand how reformist policy has altered the political attitudes and behaviour of voters (Phillips 2017). Freed from political manipulation, are voters now empowered agents of accountability, voting to perpetuate reform? Or are they still vulnerable to politicians’ control and authority, stuck in a clientelist trap?

Learning how policy today affects politics tomorrow

To answer these questions, we need to know how voters in Bihar would have engaged in politics had they not been exposed to the governance reforms in the state over the past decade. One approach would be to compare political attitudes in Bihar before and after 2005. But much has changed over this same period, including economic growth, national politics and new national policies in recent years, so we cannot assume that any changes are due to Bihar’s own reform experiences. Instead, we need to compare citizens in Bihar today with those in a very similar socioeconomic situation but who just missed out on the reforms in the state. The best candidates are voters just across the border in Jharkhand state. Besides living in almost identical geographical conditions, residents either side of the border have equal exposure to national programmes and a shared political history due to the states’ unification prior to 2001. But Bihar voters’ experience of governance is now dictated by decisions in Patna while those in Jharkhand look to Ranchi.

Rather than acquire a statewide representative sample, the survey therefore collected responses from 3,514 citizens living in 314 villages within 4 kms. of the Bihar-Jharkhand border. By comparing the responses of respondents from each state using a geographic regression discontinuity methodology, we can start to understand how recent governance changes have affected politics.

Voters in Bihar expect better governance…

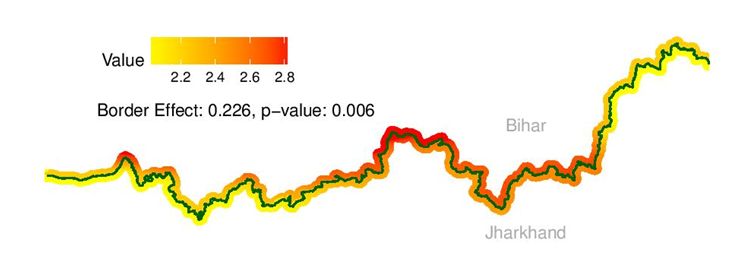

The most consistent finding of the research is that Nitish Kumar’s policy reform succeeded in encouraging voters to support his reform agenda. In Bihar, voters were more optimistic that the incumbent would provide public goods such as roads, education, and infrastructure if they were re-elected. They were more confident that corrupt politicians would be caught. Bihar voters even seem to have distanced themselves from dependence on personal political connections, with less dense connections to government networks. And crucially they were more confident that other voters would punish politicians that performed poorly, as shown in Figure 1. All these differences indicate that, compared to those in Jharkhand, Bihar voters were more confident and expected better governance in the future.

Figure 1. Perceived likelihood (5-point scale) that other voters will punish poorly performing MLAs

…But voters are yet to change their behaviour…

Notes: (i) MLAs stands for Members of Legislative Assembly.

Notes: (i) MLAs stands for Members of Legislative Assembly.(ii) The values are predicted from regression dicontinuity method.

Despite this confidence, Bihar voters showed no deep change in political attitudes and behaviour. Acts of clientelism were no more unacceptable; voters were no more likely to make demands on their politicians; and when forced to choose between hypothetical candidates, they were no more likely than voters in Jharkhand to choose a high-performing politician over one who shared their caste or who engaged in clientelism.

…And voters may even be disengaging from politics

In fact, Bihar’s reform programme may even have had an unexpected negative side-effect on voters’ political engagement. Attendance at villagewide ‘Gram Sabha’ meetings is weaker than in Jharkhand and trust in a range of political institutions is lower. It is possible that this is the result of reform in Bihar reducing opportunities for politicians to mobilise voters through material handouts, limiting voters’ engagement with the State.

Policy implications

These findings suggest an important opportunity for reformers to extend their own political lifespan – reform can produce political rewards by encouraging more confident voters to set high standards of government performance that only reformers can meet. So while many existing studies have documented the economic, social, and health effects of more rule-based programmatic policy, this research also demonstrates the political rewards to reform. This provides an additional motivation and explanation for politically-astute reform.

However, the findings also suggest that reform efforts may be particularly hard to sustain. When the initial reformer moves on, or a clientelist politician comes to the fore, voters may remain vulnerable, find it hard to coordinate with other voters, and revert to clientelist practices. Additional efforts may be required to reduce vulnerability through economic growth and poverty reduction. At the same time, new longer-term vehicles for embedding reform such as more disciplined and policy-focussed political parties may be necessary.

Finally, to counter the risks of declining trust and participation, new avenues of participation and new channels for generating trust between a distant State and citizens may be essential.

Further Reading

- Chakrabarti, R (2013), Bihar Breakthrough: The Turnaround of a Beleaguered States, Rupa Publications.

- Larreguy, H, J Marshall and L Trucco (2015), ‘Breaking Clientelism or Rewarding Incumbents? Evidence from an Urban Titling Program in Mexico’, Working Paper.

- Muralidharan, K and N Prakash (2013), ‘Cycling to School: Increasing Secondary School Enrolment for Girls in India’, International Growth Centre (IGC) Working Paper. Available here.

- Phillips, J (2017), ‘Can Bihar break the clientelist trap? The political effects of programmatic development policy’, IGC Working Paper.

- Singh, NK and N Stern (2013), The New Bihar, Harper Collins Publishers.

- Sinha, A (2011), Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar, Penguin Press.

- Somanathan, R and H Kumar (2013), ‘Evaluating the effects of targeted transfers to ‘Mahadalits’ in Bihar’, IGC Working Paper.

- Verma, P, C Kumar and A Gahlaut (2014), ‘Attendance for Entitlement? An Analysis of the 75% Attendance Conditionality to Avail School Entitlements in Bihar’, IGC Working Paper S-34203-INB-1.

14 November, 2017

14 November, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.