In the second of two articles about the implementation of Forest Rights Act, Bharti Nandwani uses data on land conflicts to investigate why land disputes increased after the introduction of FRA. She points to the prevalence of contradictory legislation, highlighting the case of compensatory afforestation funds which are disbursed in a way that encroaches upon land cultivated by forest dwellers. She emphasises the need to recognise the superior knowledge of those communities and give them the responsibility of managing and conserving forests.

Restoration and enhancement of forests is one of the stated goals of governments worldwide, including in India. The innumerable benefits that the forest ecosystem offers to the environment makes it a critical resource for our survival. Being a common pool resource, it is used by many groups, and it is hard to exclude any group from using it. Therefore, defining ownership and granting management rights over forests has important implications for its sustainable use. However, India – where 22% of geographical area is covered by forest – has a long history of contested land ownership over forests, between traditional forest dwelling communities, most of which are Scheduled Tribes (STs), and the government.

Forest land rights in India

STs have been living in forest areas for centuries without holding formal titles, whereas the government only assumed legal rights over forest land in the colonial era. In the pre-colonial period, local communities managed forest resources, deriving their livelihood from it with little government control. However, colonial forest policy through the Indian Forest Act of 1865 brought a large part of forest area under government ownership, rendering the traditional claims of millions of forest dwellers illegal. Government control over forests was carried forward into the post-independence period without settling the rights of forest dwellers. The lack of formal titles coupled with growing industrial needs led to the diversion of forest lands for other uses and the eviction of millions of forest dwellers. This has led to conflicting claims between government and forest dwellers over ownership of forest land in many cases.

In 2008, the Indian government introduced a landmark legislation, the Forest Rights Act, to recognise traditional forest dwellers’ superior knowledge of the forest ecosystem and give them responsibility of managing and conserving. The FRA was introduced to recognise individual titles to land that forest dwellers had traditionally been cultivating, and community titles giving them the right to ownership of minor forest produce (which has the potential to significantly supplement their incomes) as well as the right to manage and conserve forests.

The study

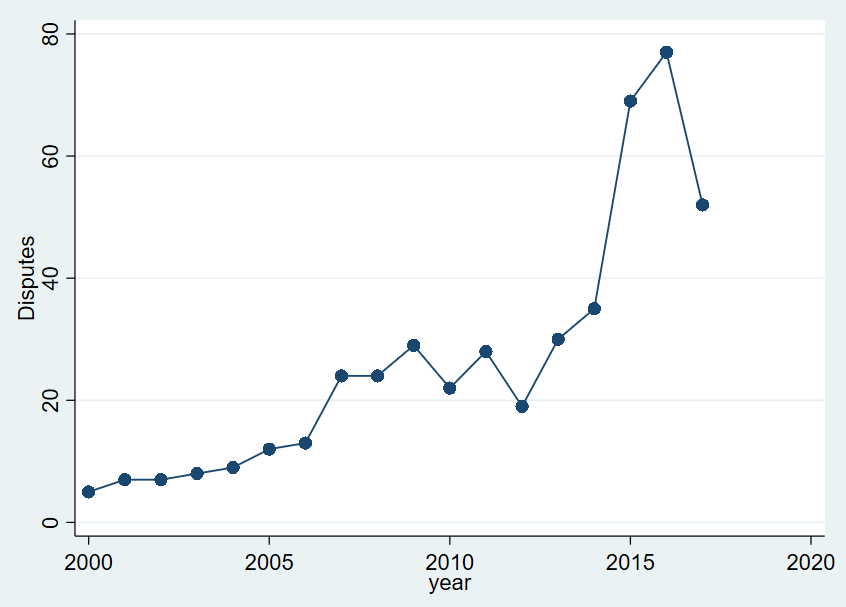

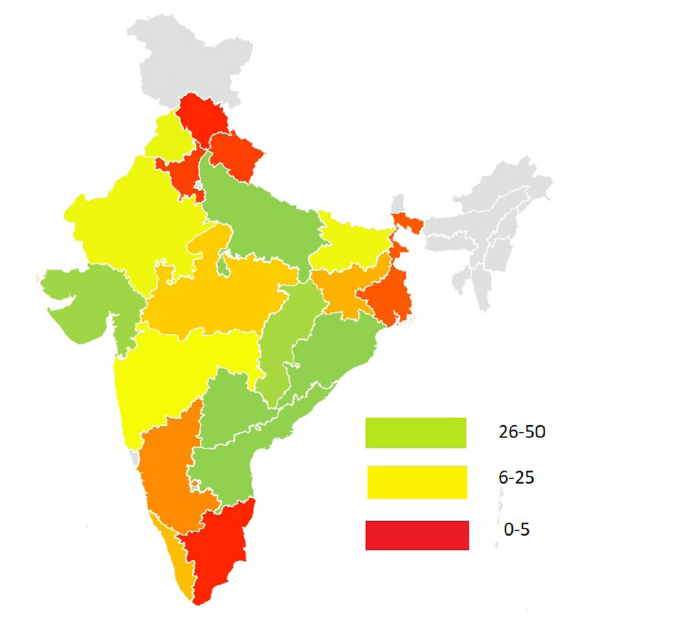

Although it has been more than a decade since the enactment of the FRA, the act has not yet fully achieved its stated goal of recognition and protection of land rights of forest dwellers. In a recent research paper (Nandwani 2022) I use data from a recently developed Land Conflicts Watch (LCW) database to show that conflicting claims to forest land by forest dwellers and government have increased after the FRA’s enactment. Figures 1 and 2 present the temporal evolution and geographical distribution of land disputes (defined as conflicting claims of land ownership) in the country. Figure 1 shows an increase in land disputes post-2008, and Figure 2 shows these disputes are concentrated primarily in high forest cover states of Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra.

Figure 1. Number of land disputes in India, from 2000-2017

Figure 2. Distribution of land disputes in India by state, from 2000-2017

I employ a difference-in-difference methodology and compare the likelihood of land disputes in high and low forest cover areas before and after 2008. For the reported trend break to be indicative of change because of the FRA, I make sure that there are no differential trends in land disputes in high and low forest cover districts before 2008. I also check the robustness of these results to existing state policies, presence of minerals, intensity of Maoist insurgency and economic activity. While an increase in land disputes after a legislation that seeks to provide secure land tenure to traditional forest dwellers might seem puzzling, similar findings have also been observed in the context of forest land rights in Thailand and Brazilian Amazon (Christensen and Rabibhadana 1994, Alston et al. 2000, Schirmer 2007, De Oliveira 2008).

I examine the reason for this and take a closer look at the existing legal set up to unfold the reason for the increased disputes after FRA. After independence, in addition to retaining the colonial forest policy of government ownership of forest land, the Indian government enacted a number of forest conservation and wildlife protection laws like Forest Conservation Act (FCA), 1980 and Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. These legislations consider forest dwellers as threats to forest and wildlife conservation and have a number of provisions that negate the rights of forest dwellers. After the FRA’s enactment, there has never been an attempt to amend these laws to be consistent with the provisions of FRA. Such contradictory legislations have resulted in legal ambiguity which has paved the way for competing claims.

One stark example of such a legislation is the way in which the funds disbursed to states under compulsory afforestation mandate of the FCA, 1980 are being used. The FCA, 1980 requires entities diverting forest land for non-forest purposes to pay an amount equivalent to the net present value of the forest land to states in a “compensatory afforestation fund'', which is managed by the ad hoc Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA). As per CAMPA, states have to use this fund for afforestation activity to compensate for the lost forest reserve. This mandate was however not adequately amended after FRA to recognise that forest dwellers are responsible for forest conservation. Although the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act, passed in 2016, mentions that forest dwellers should be consulted before carrying out plantations on their land. However, how these consultations should be carried out and what the implications are of not respecting forest dwellers’ decisions are unclear in the law.

Using LCW data, I find that around 154 new cases of land disputes over forest lands between forest dwellers and government were reported between 2008 and 2017, and 45 to 52% of these cases started due to contradictory provisions in conservation legislations. A brief summary of the land dispute incidents provided in the LCW database suggest that most conservation related conflicting claims on forest land were made because the forest department does not rely on community consent for managing forests, and conducts afforestation drives on land cultivated by forest dwellers. These are lands where forest land titles have either been awarded to forest dwellers, or which are awaiting the final decision regarding titles. This finding is in line with a number of studies that have shown that existence of contradictory tenure policies increases the chances of conflicting claims and disputes by creating insecurity about land tenure (Alston et al. 2000, De Oliveira 2008, Riggs et al. 2016).

Data on disbursement of CAMPA funds to states shows that these disbursements have consistently increased from 2009 to 2015, suggesting an increase in the extent of afforestation activity that the state is required to do, which in turn implies an increase in the chances of violation of the FRA. A simple analysis using state-wise disbursements of CAMPA funds and land disputes cases shows that instances of conflicting claims between forest dwellers and forest departments or the government are significantly higher wherever there are increases in CAMPA funds’ distribution.

Policy implications

This research highlights the challenges associated with implementing FRA without simultaneously adapting existing forest conservation legislations. Even though CAMPA funds were introduced with the objective of restoring forests, an unintended consequence has been that they have increased land disputes. This is an example of how conflicting conservation and land tenure legislations have undermined the ownership and conservation rights of forest dwellers. The need of the hour is for the government to harmonise existing forest conservation and land tenure legislations that are interfering with conservation efforts and the recognition of rights of forest dwellers. An immediate and first step could be to give forest dwellers, who have been recognised to have better know-how of the forest ecosystem, the responsibility or oversight in spending compensatory afforestation funds to improve forest cover.

The implementation of the FRA led to an increased demand for land title recognition, which in turn improved the political participation of Scheduled Tribes in Odisha. The first article (‘Forest Rights Act: Political participation of indigenous communities’) explores this question further and can be read here.

Further Reading

- De Oliveira, Jose Antonio Puppim (2008), "Property rights, land conflicts and deforestation in the Eastern Amazon", Forest Policy and Economics, 10(5): 303-315.

- Alston, Lee J, Gary D Libecap and Bernardo Mueller (2000), "Land Reform Policies, the Sources of Violent Conflict, and Implications for Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon", Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 39(2): 162-188.

- Christensen, Scott R and Akin Rabibhadana (1994), “Exit, Voice, and the Depletion of Open Access Resources: The Political Bases of Property Rights in Thailand”, Law and Society Review, 28(3): 639-655.

- Nandwani, Bharti (2022), “Community forestry and its implications for land related disputes: Evidence from India”, European Journal of Political Economy,73: 102155.

- Schirmer, Jacki (2007), "Plantations and social conflict: exploring the differences between small-scale and large-scale plantation forestry", Small-scale Forestry,6(1): 19-33.

- Riggs, Rebecca Anne, et al. (2016), "Forest tenure and conflict in Indonesia: Contested rights in Rempek Village, Lombok", Land Use Policy,57: 241-249.

22 September, 2023

22 September, 2023

By: Giri Rao 23 September, 2023

Excellent Analysis