The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Rights) Act, 2006 adopts a rights-based approach to forest conservation and seeks to place local communities at the centre of forest governance. In this note, Santosh Gedam presents the case of the Pachgaon village in the state of Maharashtra, which – through the recognition of community forest resource rights enshrined in the Act – has made significant progress in sustainably and equitably managing common-pool resources and generating local livelihoods.

The United Nations defines a rights-based approach (RBA) as an approach to conservation that respects and seeks to protect and promote recognised human rights standards. India’s Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 – commonly called the Forest Rights Act (FRA) – imbibes this idea of RBAs to conservation (Kashwan 2013). The parliament has made an unprecedented proclamation to undo ‘historical injustice" against indigenous communities (Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers), and this law intends to radically alter the landscape of forest governance in the country by recognising the central role of the local communities (Sarin and Springate-Baginski 2010). Several studies have flagged issues such as low awareness among forest-dwellers regarding the law, lack of accountability of the implementing actors, outright exclusion of protected-area villages1 from recognition of their customary rights on forest land, among others. At the same time, some emerging evidence has suggested positive outcomes. Sahu (2020) reports the differences in the price paid for harvested minor forest produce (MFP) Tendu during auctions under two regimes in Gadchiroli district in Maharashtra – forest department facilitated, and community monitored. During 2014-2016, in the case of forest department facilitation, it was Rs. 2,774, on average, while during 2017-2019, in the case of community monitoring it was Rs. 5,873, on average. With average annual inflation of about 5% during 2016-2017 and in the absence of any drastic changes in the Tendu market, the jump in the actual auction price could suggest inefficiency in forest department-facilitated auction. However, evidence on other intermediate or final outcomes – such as improvement in household income and impact on consumption, education, and health indicators – in villages where forest rights are recognised, remains limited (Sahu 2020, Pingua 2015).

In this note, I seek to contribute to the existing knowledge on the globally emerging RBAs to forest conservation, in order to strengthen the arguments supporting the recognition of community forest resource rights (CFRRs). I present a case study of Pachgaon village in Chandrapur district of the state of Maharashtra. Pachgaon village comes under the Tohogaon panchayat. The village comprises 63 households with 224 villagers (110 women and 114 men), of which STs and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers are around 70% and 30%, respectively, as per the 2011 Census. As part of the study, I conducted informal interviews (with members of forest management committees and other villagers), and transect walks2 in the forest between November 2020 and March 2021, and also analysed available MNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act)3 data, and demographic data at the gram panchayat4 level.

A reserved water body for wild animals in Pachgaon

Recognition of community rights to forest resources in Pachgaon village

The Pachgaon gram sabha was given the title to 2,487 acres of forest land in 2012. Up until then, it was a struggle for the villagers to find regular work due to limited work options outside the agricultural season. Around 2010, after hearing from the neighbouring village of Parsodi that MNREGA pays wages directly into bank accounts (villagers referred to this as a ‘monthly salary’), villagers from Pachgaon started demanding MNREGA work. However, they soon realised that the physically demanding nature of manual work under MNREGA could not be continued for a long period.

Pachgaon gram sabha office

In the context of the search for sustainable sources of income, a member of an NGO (non-governmental organisation) introduced villagers to the newly enacted FRA, and from this came the idea of claiming CFRRs. This triggered several rounds of gram sabha discussions, with the villagers. The initial expenses of preparing the claim, its submission, and follow-up, were met via contributions of Rs. 3 per household.

The first thing that Pachgaon did after getting the CFRRs title was to develop village-level rules for conservation and sustainable management of the forest. The Pachgaon gram sabha made it compulsory for all households to submit their suggestions – written or otherwise – for the management of community forest resources. The idea behind inviting suggestions from every household, even if it occasionally proved routine or repetitive, was to enhance participation in the process, and develop a sense of ownership for the management of the recognised forest. After receiving 800-odd suggestions from households, each of these was discussed and debated in the gram sabha. Women were particularly encouraged to participate in the discussions. The FRA’s rules mandate that at least one-third of the members present should be women, but does not have any participation requirements (that is, speaking in meetings). The entire rule-making process ensured that every person gets the opportunity to speak and no one person or group dominates the process. After months of deliberation, 115 suggestions were finally accepted and ratified by the gram sabha, and these formed the forest management rules.

Post recognition of CFRRs, every member of the identified age group (18-60 years), is required to participate in a ‘forest vigilance group’ to monitor forest activities and record their updates on the flora and fauna in an ‘observation register’. A guide we spoke to, who accompanied us on a transect walk, said that all processes originate from the village rules, and their compliance is strictly observed with appropriate sanctioning measures in case of violations. At the beginning of the transect walk through the community forest, I was asked to enter my basic details in the forest visit register. It was revealed that all visitors’ details are recorded to track the purpose of the visit, and a visitor can enter the forest only after receiving approval from the community-appointed guard on the spot. According to a respondent, the registration process ensures that no unauthorised person enters the forest. He also narrated an incident where a ‘conservator of forest’ (a local forest bureaucrat) once entered their forest without intimation, and this led to tension between the forest department and the villagers. The conflict resulted in the filing of multiple police complaints, and the matter was settled only after the intervention of a local MLA (member of legislative assembly) and minister of the state government. This incident illustrates a sense of ownership towards the forest among Pachgaon’s villagers.

Bhivgad, a sacred place in Devrai

The Pachgaon gram sabha has set aside around 85 acres of forest land, exclusively as inviolate zones called Devrai (deity’s place) as a habitat for wild animals. They believe that wild animals also need separate and inviolate habitats and thus, the gram sabha identified a suitable patch for this purpose. Despite several incidences of tiger and other wild animal attacks in villages in the vicinity of Chandrapur, as per the respondents, Pachgaon has not witnessed a single case of a wild animal attack on a human for several years. Amid the Devrai is a place called Bhivgad , which is considered sacred by the villagers. In Bhivgad, several idols of animals are kept for the purpose of worshipping.

Post-recognition outcomes have attracted visits by newly recruited officers of the Indian Forest Services (IFS) as Pachgaon illustrates how CFRRs can enable the protection of wildlife by creating inviolate zones, conservation of biodiversity by maintaining records, and support for sustainable and equitable livelihoods.

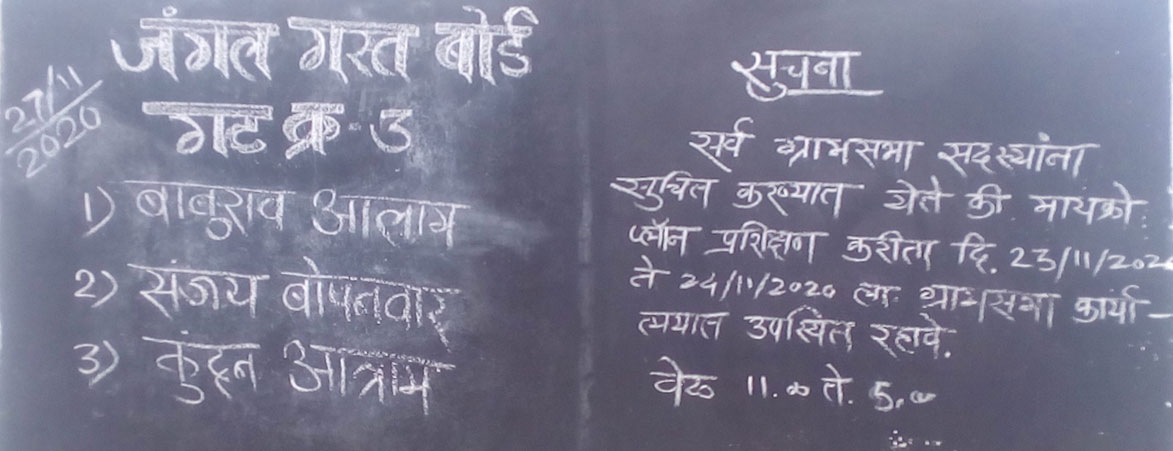

Notice board of the forest vigilance group with group member names and announcements

Sustainable, equitable resource management and livelihood generation

Pachgaon’s community forest has various MFP, of which bamboo occupies the largest area. The village rules regulate bamboo harvesting as a source of daily livelihood. There is a specific quota of 50 bamboos per person in the identified age group per day, to ensure equity in benefitting from bamboo income. Any bamboo harvested in excess of this limit is confiscated and it becomes the property of the gram sabha. The rate for bamboo is fixed by the gram sabha, and weekly payments are promptly made to the beneficiaries’ bank accounts. In the past eight years, this sustainable management of community forests has generated a surplus of almost Rs. 35 million for the gram sabha.

Another outcome of CFRRs recognition is the elimination of dependencies on MNREGA. While the demand for job cards at the gram panchayat level has increased from 60.6% in 2011-12 to 68.6% in 2019-20 of the eligible population, as per the MNREGA public data portal, this has come entirely from the other village of the Panchayat. During interviews, respondents revealed that no household in Pachgaon seeks work under MNREGA due to the physically demanding nature of the work. Pachgaon offers customised jobs to its community members. Without recognised CFRRs, 73.4% of households in the neighbouring village of Tohogaon still continue to depend on MNREGA work as of 2019-20.

A member of the gram sabha committee noted how the rules of forest management have protected villagers during the pandemic, at a time when farmers elsewhere are suffering. In Pachgaon, the recognition of CFRRs has helped make the village self-reliant, as they do not have to seek work outside of the village. Their current focus is on processing and value addition to various MFP harvested by households from the forest. Over the period of collection, they have amassed tonnes of MFP in their warehouse. A few years earlier, they purchased five acres of land adjacent to the village boundary for Rs. 500,000 for the processing and value addition of these MFP. He highlights the gram sabha’s resolve to diversify sources of livelihood since bamboo-based income may decline in the future as the bamboo stock is nearing the end of its natural life of around 20 years.

Pachgaon’s learning experience and achievements have now enhanced its knowledge and capability to negotiate with market forces. Unlike before, in 2020, due to the pandemic, the Pachgaon village used a web-based tendering process for the sale of bamboo harvested from the forest. The new tendering process countered the local cartel of contractors who would collude to keep bid prices deliberately low, thereby depriving the villagers of a fair income. Recalling his auctioning experience, a respondent (gram sabha member) in charge of MFP auctioning mentions that in the year 2020, due to the e-tendering of bamboo, the contractor nexus was broken – leading to a higher price for harvested bamboo compared to that of the last few years.

Pachgaon is also planning to pay a monthly pension to all its villagers above 60 years of age – an idea that is motivated by the government employment system. Pachgaon’s gram sabha believes that they should provide social security, and no person above 60 years of age should have to worry about earning a livelihood.

Interaction with workers

Resolving the ‘social dilemma’ and building resilience

Scholars doubt the efficacy of the management of the commons by the community on grounds of over-utilisation and an ultimate ‘tragedy of the commons’ (Hardin 1968), but the case of Pachgaon is evidence of how community members can come together and resolve what is termed in the literature as ‘social dilemma’, to sustainably and equitably manage their common-pool resources (Ostrom 1998). Proponents of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ theory recommend the privatisation or State control of such resources to ensure resource sustainability. On the other hand, Nobel Laureate Ostrom argued that these resources can be efficiently managed by local communities.

Some estimates suggest that around 170,000 villages in India have customary forests (traditionally used forest in the vicinity of the village) and can potentially benefit from recognised CFRRs (Rights and Resources Initiative et al. 2015). This accounts for over 26% of the total number of villages in India, and indicates the scale of impact FRA can have.

Among other developing countries, Nepal has democratised its forest management by recognising rights to develop, use, conserve, and manage, of more than 18,000 villages. A recent study (Oldekop et al. 2019) finds that this has significantly reduced poverty and deforestation, and highlights clear trade-offs between poverty and deforestation. Thus, community forests offer a win-win solution. Pachgaon’s case provides evidence from India in this regard and suggests that if CFRRs are recognised, thousands of villages can achieve sustainable and equitable livelihood without being compelled to live in poverty or distress-migrating to cities. Pachgaon is testament to the fact that recognising CFRRs can improve villagers’ resilience, which has become critical during the economic shock brought on by Covid-19.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Protected areas are national parks and wildlife sanctuaries as declared under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. Forest rights advocates claim that the move to notify several tiger reserves as protected areas in 2007, was actually intended to exclude villages in those areas from recognition of forest rights.

- A transect walk is generally conducted during the initial phase of the fieldwork and is a systematic walk along a defined path (transect) across the community/project area together with the local people to explore the forest boundary, landmarks, and resource allocations by observing, asking, listening, looking and producing a transect diagram.

- MNREGA guarantees 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at the prescribed minimum wage.

- Gram sabha is a body consisting of people registered in the electoral rolls within the area of villages in the panchayat. The members of the gram sabha elect the members of the gram panchayat, which is the cornerstone of local self-government organisation in India in the panchayati raj system at the village or small-town level and has a sarpanch as its elected head

- Bhiv is a legend in folk stories, and gad means place.

Further Reading

- Hardin, Garett (1968), “The tragedy of the commons”, Science, 162(3859): 1243-1248.

- Kashwan, Prakash (2013), “The politics of rights-based approaches in conservation”, Land Use Policy, 31: 613-626. Available here.

- Lele, S, A Khare and S Mokashi (2020), ‘Estimating and Mapping CFR Potential: For Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra’, Report, Centre for Environment & Development, ATREE.

- Oldekop, Johan A, Katherine RE Sims, Birendra K Karna, Mark J Whittingham and Arun Agarwal, “Reductions in deforestation and poverty from decentralized forest management in Nepal”, Nature Sustainability, 2: 421-428.

- Ostrom, Elinor (1998), “A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action: Presidential Address, American Political Science Association, 1997”, The American Political Science Review, 92(1): 1-22. Available here.

- Pingua MK (2015), ‘Implementation of FRA in Protected Areas’, Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India. Rights and Resources Initiative, Vasundhara and Natural Resources Management Consultants (2015), ‘Potential for Recognition of Community Forest Resource Rights Under India’s Forest Rights Act’, Preliminary Report.

- Sahu, Geetanjoy (2021), “Implementation of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Rights) Act 2006 in Jharkhand: Problems and Challenges”, Journal of Land and Rural Studies, 9(1): 158-177. Available here.

- Sarin, M and O Springate-Baginski (2010), ‘India’s Forest Rights Act -The anatomy of a necessary but not sufficient institutional reform’, IPPG Discussion Paper Series No. 45. Available here.

06 August, 2021

06 August, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.