This article examines the impact of a complete ban on the sale and consumption of alcohol in Bihar in 2016 on the incidence of intimate partner violence against women. Using NFHS data, it finds that after the ban, women in Bihar reported that their husbands were less likely to consume alcohol, and they were less likely to experience domestic violence. It also highlights the complementary role of self-help groups in increasing women’s empowerment and making them less susceptible to abuse.

Approximately 35% of women in India face some form of intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetime, whereas the global average stands at 27% (World Health Organization, 2018). Such high prevalence of IPV is often due to several reasons, such as early marriage of women (Roychowdhury and Dhamija 2021), son preference (Priya et al. 2014), low rates of female education (Angelucci and Heath 2020), a family history of abuse for either partner (Bensley et al. 2003), husband’s unemployment (Bhalotra et al. 2021), smaller dowries (Bloch and Rao 2002), etc. High rates of IPV have both immediate and long-term consequences for women, including poor health, unintended pregnancies and induced abortions (Ahinkorah 2021), mental health conditions like depression (Karakurt et al. 2014) and anxiety disorders (Ellsberg et al. 2008), low labour force participation (Chakraborty et al. 2018), and low child survival rates (Koenig et al. 2010) to name a few.

As a part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, governments across the world have committed to eliminate all forms of violence against women. Though it might not be straightforward to address underlying factors such as traditional gender norms which have been responsible for higher IPV, various safeguards have been adopted to reduce spousal violence, such as the establishment of women police stations (Amaral et al. 2021), small cash transfers to women (Bobonis et al. 2013), one-stop centres, helpline numbers, etc. However, most of these measures have been targeted towards women.

One effective strategy to minimise domestic abuse involves regulating spousal alcohol consumption. Research has consistently found a positive association between the partner's alcohol use and IPV (Leonard 2005, Luca et al. 2015). It has been argued that drinking can impair judgment, lower inhibitions, and increase aggression, making individuals more likely to engage in violent behaviour (Cook and Durrance 2013).

However, the estimates of the prohibition on IPV in the existing literature suffer from omitted variable bias due to confounding factors, such as the coincidence of the ban with other gender-specific policies or the selective imposition of the ban in areas that are unsafe for women. In our study (Debnath et al. 2023), we attempt to address these concerns by exploiting variation in pre-ban consumption of alcohol to understand the effect of an alcohol ban in the state of Bihar on IPV.

Impact of the alcohol ban in Bihar

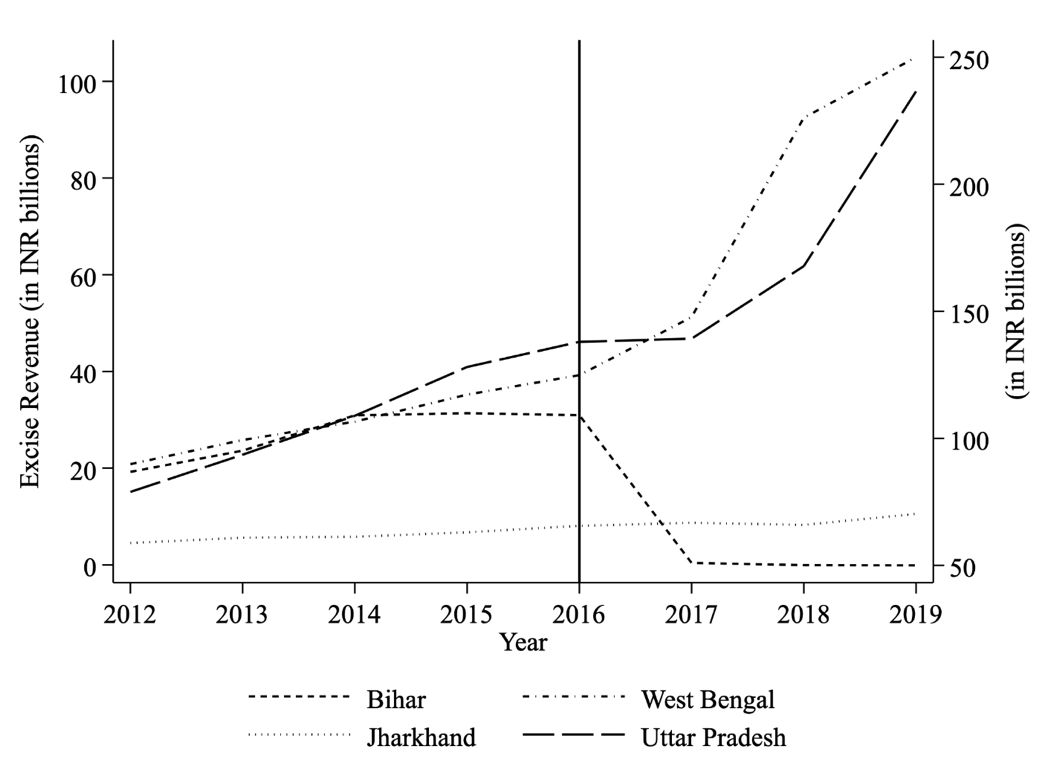

In April 2016, the state government in Bihar implemented a complete state-wide prohibition on the sale, purchase, consumption, and manufacture of alcohol.1 Using data from the Combined Finance and Revenue Accounts of the Union and State Governments for different years, we plotted the revenue generated from sales of various types of alcohol in Bihar and its neighbouring states in Figure 1. As expected, we observe a sharp fall in excise revenue for Bihar post-2016, indicating that the ban was indeed effective in reducing the legal sale and consumption of alcohol across the state (Chaudhuri et al. 2023).

Figure 1. Year-wise excise revenue from alcohol, across states

Notes: i) Bihar, West Bengal and Jharkhand’s tax revenue from liquor are plotted on the primary axis; Uttar Pradesh’s tax revenue is plotted on the secondary axis. ii) The vertical line depicts the year of the alcohol ban in Bihar.

Theoretically, the impact of alcohol bans on IPV is unclear. Though studies find a strong relationship between lower liquor consumption and improved marital relations as well as fewer discords (Luca et al. 2015), it is important to note that strict enforcement of alcohol bans could also have negative consequences for women. After the ban, desperate alcoholic spouses may eventually lash out at their partners out of frustration. For instance, Iyengar (2009) finds that laws mandating arrest to address police inaction for a domestic violence report led to an unintended increase in IPV.

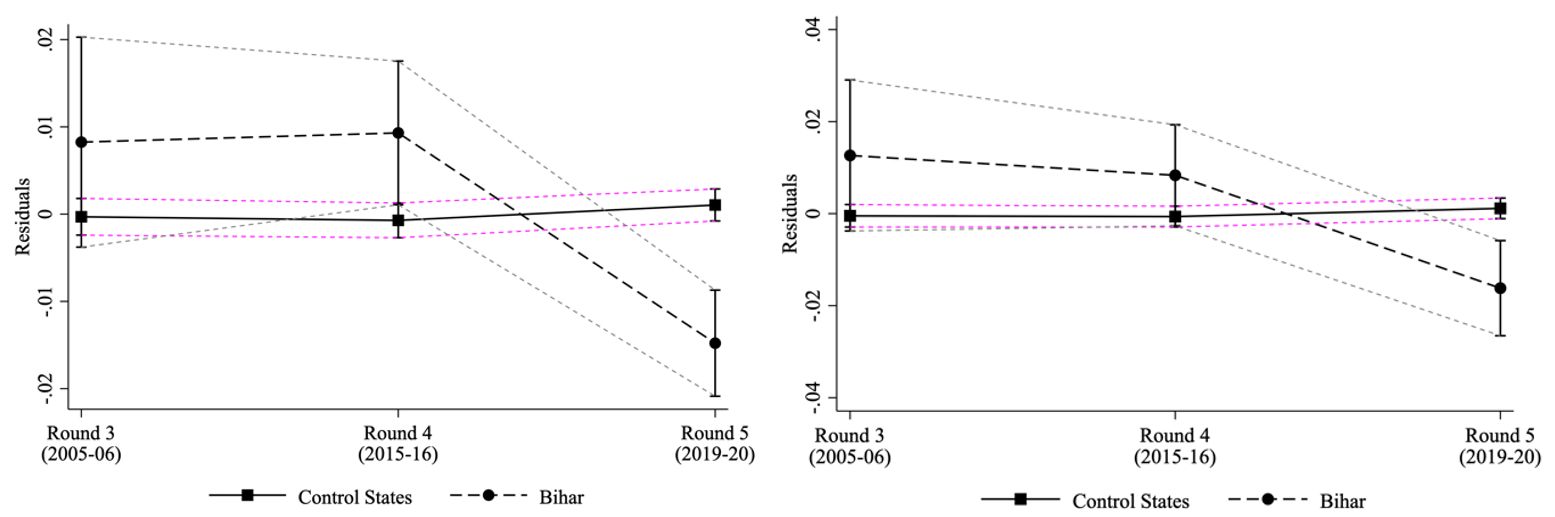

Using multiple waves of the nationally representative National Family Health Survey (NFHS) and a difference-in-difference strategy2, we find that women residing in Bihar reported a drop in their husband's alcohol consumption after the ban was implemented, compared to women in other states. Furthermore, we find that women living in Bihar were less likely to face domestic violence (including physical, sexual, or emotional) after implementing the ban. We also test for parallel trends (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Parallel trends for frequent alcohol consumption (left) and severe physical violence (right)

Notes: i) The y-axis records the unexplained variation in the husband’s alcohol consumption (left panel) and severe physical violence faced by the woman (right panel) after controlling for state and round fixed effects using NFHS datasets. ii) States that had temporary or district-wise bans on alcohol previously or currently have been excluded from our analysis.

Dixit et al. (2023) employ a similar empirical strategy to find a negative impact of the ban on domestic violence. However, a major threat to this identification is the adoption of other pro-female policies by the Bihar government around the same time that could explain the decline in IPV rates. We address this concern by exploiting variation in alcohol consumption within Bihar before the ban was implemented.

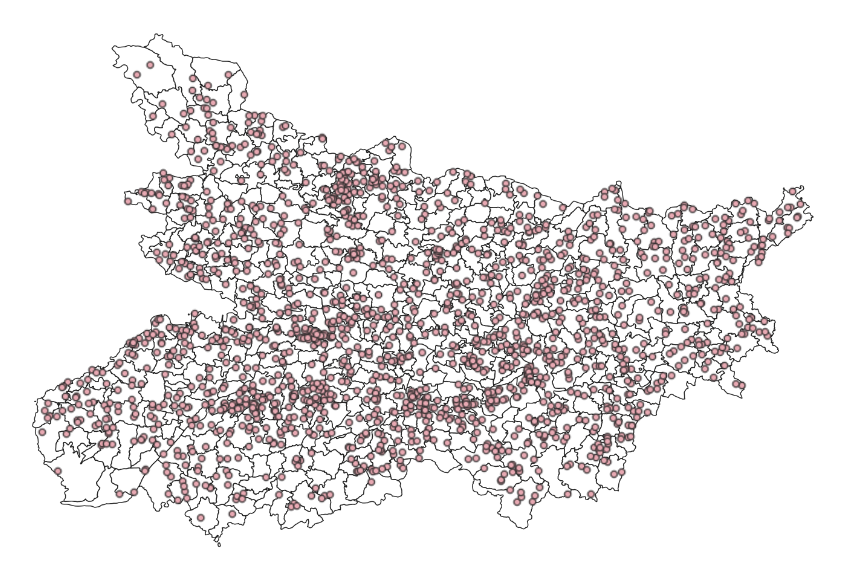

Using geospatial data from the NFHS, we compute the pre-ban intensity of alcohol consumption at a disaggregated level (sub-district or blocks)3 in Bihar (see Figure 3). We hypothesise that if the ban was effective, it should have significantly reduced alcohol consumption in areas where pre-ban alcohol consumption was relatively higher within Bihar. However, other pro-women state policies in Bihar – including Women Empowerment Policy in 2015, Mukhyamantri Balika Cycle Yojana in 2007, and Mukhyamantri Nari Shakti Yojana in 2008 – are less likely to vary by pre-ban alcohol consumption.

Figure 3. NFHS clusters across sub-districts in Bihar

Prior to the ban, IPV rates for high-alcohol consuming blocks were approximately 37-54% higher than that of the low-alcohol consuming blocks. Our results show that a woman living in a block with higher pre-ban alcohol consumption was less likely to face physical (both severe and less severe) and emotional violence respectively after the ban by 4.2-12% and 7.4% respectively. She was also 6.3 percentage points less likely to experience any restrictions from her spouse, such as not allowing her to see family or friends, not trusting her with money, knowing her whereabouts at all times, etc.

Complementarity of the alcohol ban with Self-Help Groups

In 2006, the Bihar government launched the Bihar Rural Livelihood Project (BRLP), popularly known as Jeevika, to form Self-Help Groups (SHGs) amongst marginalised women to encourage micro-credit lending and mobilise savings. Approximately 1.4 million SHGs were formed between 2006 and 2022 under this flagship project. The formation of a SHG aims to encourage financial independence amongst women, and we expect that women with greater access to resources will be less susceptible to abuse. Using the information on the date of formation for every SHG, we calculate the total number of SHGs across blocks in Bihar before the ban. We find that the impact of the prohibition on the incidence of IPV was statistically significantly higher for women residing in blocks with more SHGs compared to their counterparts residing in blocks with fewer SHGs. The evidence emphasises the importance of social networking groups in offering financial and other assistance to reduce IPV rates.

Policy implications

Though the alcohol ban aided in reducing alcohol-related violence and improving public health, it has often been criticised for increased smuggling and bootlegging in the state, a loss of revenue for the government, an increase in other forms of substance abuse, and diversion of police resources towards enforcement of the ban– leading to a rise in overall crime in the state (Agarwal 2017, Dar and Sahay 2018, Jha 2022). Few media articles also covered the rise in deaths due to the consumption of spurious alcohol in the state (Singh 2023). Therefore, there is a need to carefully evaluate the trade-off between the loss to the exchequer and the welfare implications of the ban, to arrive at a conclusion on whether such policy could be extended to other states.

Despite these policy limitations, our paper attempts to highlight the impact of the ban specifically on reducing gendered violence toward women. We further shed light on the significance of other government policies, like Jeevika, that aim to empower women in augmenting the overall effect of the ban on IPV. SHGs play a pivotal role in organising women and offering access to livelihood and social protection. The absence of these financial and communal resources could explain why women continue to live in abusive relationships. Consequently, implementing policies designed to improve the financial autonomy of females could effectively eliminate the ill-treatment they face.

Notes:

- Several other states have previously imposed temporary or district-wise bans on alcohol, like Gujarat, Mizoram, Nagaland, Lakshwadeep, Manipur, and Kerala. We do not consider these states in our analysis.

- A difference-in-difference strategy is used to compare the evolution of outcomes (in this case, IPV) over time in similar groups, where one was affected by an event (in this case, the alcohol ban in Bihar) while the other was not.

- Since there are only 38 districts in Bihar, there is not enough variation to exploit at the district level.

Further Reading

- Agarwal, Neeraj, Chandra Mani Singh, Chandramani Kumar and AK Shahi (2017), “Assessment of implications of alcohol prohibition in Bihar: A pilot study”, Indian Journal of Community and Family Medicine, 3(1): 63-66.

- Ahinkorah, Bright Opoku (2021), “Intimate partner violence against adolescent girls and young women and its association with miscarriages, stillbirths and induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from demographic and health surveys”, SSM Population Health, 13: 100730.

- Amaral, S, S Bhalotra and N Prakash (2021), ‘Gender, Crime and Punishment: Evidence from Women Police Stations in India’, CESifo Working Paper No. 9002.

- Angelucci, Manuela and Rachel Heath (2020), “Women Empowerment Programs and Intimate Partner Violence”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110: 610-614.

- Bensley, Lillian, Juliet Van Eenwyk and Katrina Wynkoop Simmons (2003), “Childhood family violence history and women’s risk for intimate partner violence and poor health”, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25(1): 38-44.

- Bhalotra, Sonia, Uma Kambhampati, Samantha Rawlings and Zahra Siddique (2021), “Intimate Partner Violence: The Influence of Job Opportunities for Men and Women”, The World Bank Economic Review, 35(2): 461-479.

- Bloch, Francis and Vijayendra Rao (2002), “Terror as a Bargaining Instrument: A Case Study of Dowry Violence in Rural India”, American Economic Review, 92(4): 1029-1043.

- Bobonis, Gustavo J, Melissa Gonzalez-Brenes and Roberto Castro (2013), “Public Transfers and Domestic Violence: The Roles of Private Information and Spousal Control”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(1): 179-205.

- Chakraborty, Tanika, Anirban Mukherjee, Swapnika Reddy Rachapalli and Sarani Saha (2018), “Stigma of sexual violence and women’s decision to work”, World Development, 103: 226-238.

- Chaudhuri, Kalyani, Natasha Jha, Mrithyunjayan Nilayamgode and Revathy Suryanarayana (2023), “Alcohol Ban and Crime: The ABC’s of the Bihar Prohibition,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming.

- Cook, Philip J and Christine Piette Durrance (2013), “The virtuous tax: Lifesaving and crime-prevention effects of the 1991 federal alcohol-tax increase”, Journal of Health Economics, 32(1): 261-267.

- Dar, A and A Sahay (2018), ‘Designing Policy in Weak States: Unintended Consequences of Alcohol Prohibition in Bihar’, Working Paper. Available here.

- Debnath, S, SB Paul and K Sareen (2023), 'Alcohol Abuse and Abusive Husbands: Impact of a State-wide Alcohol Ban on Intimate Partner Violence', Working Paper.

- Dixit, M, S Mukherjee and J Rajan (2023), ‘Alcohol Consumption and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence from a recent policy in India’, Working Paper. Available here.

- Ellsberg, Mary, et al. (2008), “Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the who multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study”, The Lancet, 371(9619): 1165-1172.

- Iyengar, Radha (2009), “Does the certainty of arrest reduce domestic violence? evidence from mandatory and recommended arrest laws”, Journal of Public Economics, 93(1-2): 85-98.

- Leonard, Kenneth E (2005), “Alcohol and intimate partner violence: When can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence?”, Addiction, 100(4): 422-425.

- Jha, R (2022), ‘Bihar prohibition: An unmitigated disaster’, Observer Research Foundation, 15 November.

- Karakurt, Gunnur, Douglas Smith and Jason Whiting (2014), “Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Women’s Mental Health”, Journal of Family Violence, 29: 693-702.

- Koenig, Michael A, Rob Stephenson, Rajib Acharya, Lindsay Barrick, Saifuddin Ahmed and Michelle Hindin (2010), “Domestic violence and early childhood mortality in rural India: evidence from prospective data”, International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(3): 825-833.

- Luca, Dara Lee, Emily Owens and Gunjan Sharma (2015), “Can Alcohol Prohibition Reduce Violence against Women?”, American Economic Review, 105(5): 625-629.

- Priya, N, et al. (2014), ‘Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India’, Report, International Center for Research on Women.

- Roychowdhury, Punarjit and Gaurav Dhamija (2021), “The Causal Impact of Women’s Age at Marriage on Domestic Violence in India”, Feminist Economics, 27(3): 188-220.

- Singh, S (2023), ‘7 yrs since Bihar liquor ban: 199 deaths, 30 hooch cases but no conviction yet, says police data’, The Indian Express, 18 April.

27 July, 2023

27 July, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.