In this article, based on Chapter 7 of 'Decentralised Governance’, Mitra and Pal utilise Indonesia’s fiscal decentralisation to local communities in 2001 to examine how FD may differentially affect the choice of local polity and generate local political entrepreneurship in ethnically homogenous and heterogenous communities. Utilising local income and local development as proxies for local political entrepreneurship, they document that ethnically diverse electoral democracies were more effective to initiate political entrepreneurship in Indonesia, which in turn facilitated the alignment of diverse population groups.

What are the potential implications of fiscal decentralisation (FD) on changes in local leadership regimes, and can community homogeneity explain the nature of local leadership selection following expenditure shifts after decentralisation? While it is natural to expect a different pattern of budgetary allocations and spending at the local level after FD, any potential change in the dynamics of the local polity arising from the process of FD remains less obvious, thus motivating our study.

In a chapter of Decentralised Governance (Mitra and Pal 2023), we particularly focus on the effect of FD on the method of local leader selection. Whether the leader of a community reflects the preferences of the entire populace or is only sensitive to the needs of a select few (the local elite) is likely to determine the pattern of local public spending and thereby the social welfare in a community. In fact, the greater the leader’s control over the local purse strings (courtesy of FD), the more crucial the role of the local leadership’s preferences become, raising the need for a fuller understanding of how community leaders are selected.

Why community homogeneity matters in a democracy

We distinguish between electoral and participatory democracies in this respect. Electoral democracies rely on obtaining majoritarian support, which means that the interests of minorities may get overlooked. Hence, some scholars (for example, Mansuri and Rao (2013), Sanyal and Rao (2018)) have advocated direct and participatory democracy to enable the forming of a consensus. However, the success of such schemes relies (too) heavily on the presence of community homogeneity. If discourse tends to be similar among communities characterised by similarities in language, culture, and institutions, FD increases the importance of the local leader. Hence, all constituent ethnic groups would take a greater interest in the selection of the leader. If a community is largely ethnically homogeneous, the selection could take place by consensus-building; after all, the associated costs of discussion and deliberation would be low owing to the uniformity in language/culture and preferences regarding public goods.

Such costs, however, are substantially higher for ethnically diverse communities which might derail the process of consensus-building. Therefore, ethnically diverse communities may prefer electoral democracy for selecting leaders post-FD, which may also open up the political space for competition. The possibility of higher ‘rents’ from holding (local) office in the post-FD scenario may induce more entrepreneurial potential leaders into action – this should generate higher local incomes and greater development too. Using local council level data from London, Manchester and West Midlands, in Ghosh et al. (2023) we show that substantive representation of elected representatives of minority background may promote public spending for social integration in diverse communities. We also envisage that these effects are likely to be concentrated in communities where the existing economic inequality is low – it is easier for the leader to implement better policies when the economic interests of a community are more closely aligned.

The fiscal decentralisation experience in Indonesia

Our empirical investigation is motivated by the experience of Indonesia, a large emerging economy. Indonesia is also diverse along many socio-demographic markers and forms of local governance, thus making it a very apt candidate for the issues we seek to explore. The country undertook a comprehensive programme of FD, with the enactment of Law 22/99 and Law 25/99 at the turn of the millennium, which roughly coincided with the end of President Suharto’s rule. FD in post-Suharto Indonesia gave local communities more autonomy in raising local revenues, while enforcing strict budgetary cuts on spending by the central government leadership to supply development grants to these communities. This also granted administrative authority to local governments to hire staff and conduct local government affairs with minimum intervention of the central government. Instead of the central government, local community governments were made responsible to the district government, which provided the bulk of their funds after FD. In other words, the centre of power moved from the central government in Jakarta to the district headquarters.

Using the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) data, we consider 312 local communities drawn from 13 provinces (representing 83% of Indonesian population) in 1997 and 2007, two years which fall before and after the introduction of Law 22/99 and Law 25/99 in 2001. The communities represent the lowest administrative level within a district for which elections take place – these can be either rural villages (desas) or urban townships (kelurahans). Hence, we consider FD introduced by the central government to be largely exogenous to the communities under consideration.

The IFLS data allow us to categorise local polities as ‘democratic’ if the community leader is elected by voting or consensus-building among all citizens, and ‘non-democratic’ (or oligarchic) if the leader is chosen by a few citizens including the local elite, local institutions, and/or outside influence. Accordingly, we are able to characterise local political transition using changes to the method of leader selection in a given community after FD. Following our theoretical conjectures above, we distinguish between electoral (majority voting) and participatory (Musyawarah-Mufakat) democracies prevalent in Indonesia. The latter being a customary form of Indonesian decision-making based on deliberation and consensus-building regularly recognised in village gatherings.

The two tables below show the effect of community homogeneity on the likelihood of local polity, proxied by three possible variables – consensus-building (column 1), voting (column 2) or any democratisation (voting and consensus building taken together; column 3) following FD. The variable FD (shock) is a binary variable indicating the post-FD period, which takes the value 1 for the year 2007, and 0 for 1997. Our key explanatory variable is ethnic homogeneity of the community measured in different ways. Table 1 shows the estimates using the variable pop1_91, which takes a value 1 if the population share of the largest population group is greater than the median value, and 0 otherwise. Table 2 shows the corresponding estimates using the perfect homogeneity measure, where the variable pop1_100 takes a value 1 if the community has 100% population of one group only. Other controls used include community population, geographic size, whether it is rural, if Islam is the main religion, and their interactions with FD. All regressions include district dummies too.

Table 1. Homogeneity measured by the top ethnic group having above median population

|

Dependent variables |

|||

|

Explanatory |

Model 1: Consensus |

Model 2: |

Model 3: Democratisation |

|

FD (shock) |

-0.454 |

1.001* |

-0.1633 |

|

pop1_91 (dummy) |

-0.107 |

0.185*** |

0.0273 |

|

pop1_91xFD |

0.178** |

-0.093* |

0.097* |

|

Constant |

0.567 |

-0.256 |

1.1941*** |

|

R-squared |

0.158 |

0.351 |

0.0500 |

Table 2. Homogeneity measured by the top ethnic group making up 100% of the population

|

Dependent variables |

|||

|

Explanatory |

Model 4: Consensus |

Model 5: |

Model 6: Democratisation |

|

FD (shock) |

-0.522 |

1.021** |

-0.036 |

|

pop1_100 (dummy) |

-0.107 |

0.145** |

0.112 |

|

pop1_100xFD |

0.219*** |

-0.137 |

0.010 |

|

Constant |

0.5482 |

-0.1481 |

1.1797*** |

|

R-squared |

0.160 |

0.341 |

0.502 |

Notes: i) All estimates are clustered by districts; cluster-robust standard errors are shown in parentheses. ii) Significance levels: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. iii) We pool data for 1997 and 2007 together to run the regressions. The total number of regression observations is 616.

We argue that community homogeneity is exogenous, because the population composition has remained largely invariant over the decade, between 1997 and 2007. We focus on the estimated coefficients on pop1_91×FD in Table 1 and that on pop1_100 in Table 2. These coefficients account for the differential effects of community homogeneity on measures of local polity after FD. Notice, the estimated coefficient on pop1_91×FD is positive for consensus-building (model 1) and negative for voting (model 2) and both coefficients are statistically significant. This means that homogeneous communities are more likely to choose participatory (rather than electoral) democracies after FD. Similar results are obtained in models 4 and 5 using the alternative homogeneity measure.

Local income and development spending in communities

Second, we examine the link between local polity and local political entrepreneurship. We measure the local entrepreneurship of the community leader by the size of local income and local development spending in the community. We proxy local income by local revenue generated from various sources. Local development is measured by spending on new social and physical infrastructure plus the maintenance of existing social infrastructure (such as schools and health facilities) and physical infrastructure (such as roads and transport connections) at the local community level.

Given the potential simultaneity between local polities and local revenue/development spending in sample communities, we use the propensity score matching (PSM)1 method to compute the average treatment effects on the treated (ATT). In particular, we focus on the likelihood of voting and consensus-building for selection of community leaders as the two possible treatments in alternative specifications; the rest are considered as a control.

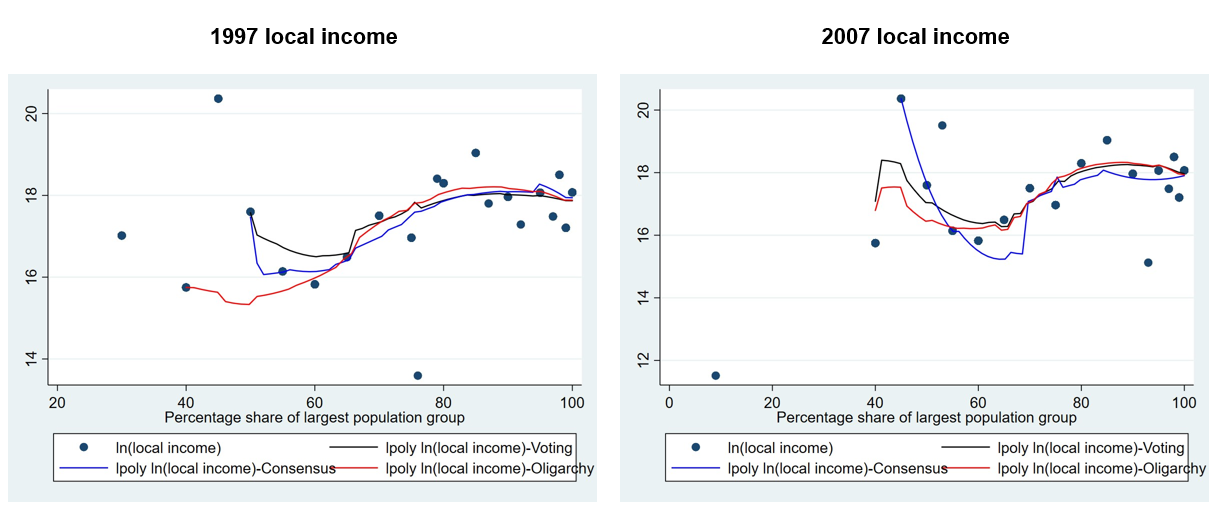

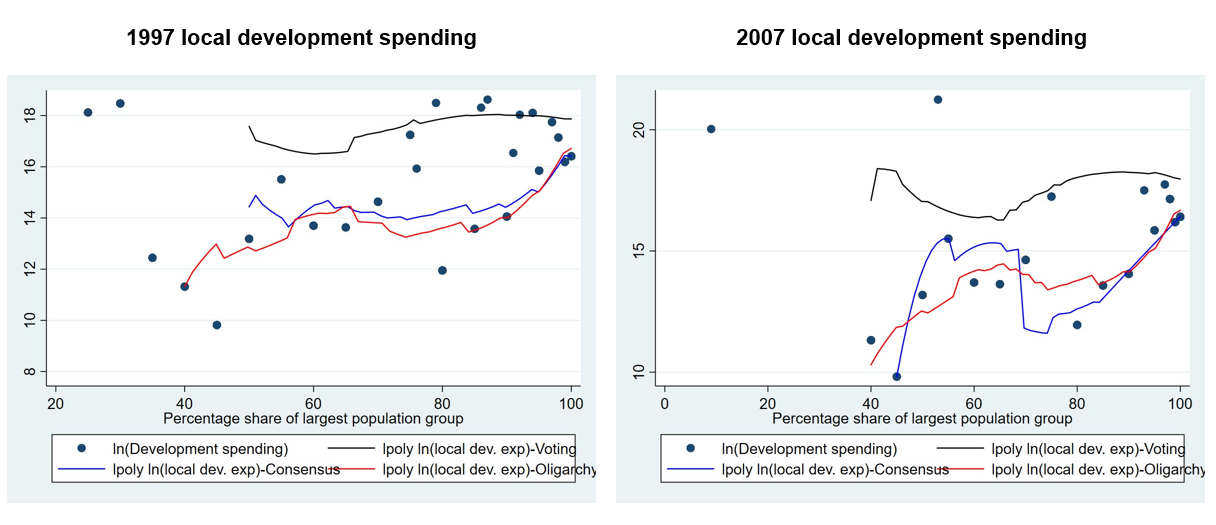

Figure 1 documents the variation in local income and local development spending by local polity (voting, consensus building and oligarchies, where the local leader is elected by local elites or institutions) when plotted against the percentage share of largest population group in 1997 and 2007. In general, higher levels of income and spending are seen in ethnically diverse communities where the most populous group make up a lower share of the population.

As the share of largest group increases, however, the distinction between different polities with respect to income gets blurred. Relative to others, voting communities continue to have the higher development spending irrespective of the level of ethnic diversity in both 1997 and 2007. These patterns tend to suggest that local political entrepreneurship that is successful to boost income and development spending more in ethnically diverse voting communities may help aligning the economic interests of ethnically diverse citizens, thus aiding efforts to overcome their collective action problems.

Figure 1. Variation in local income and local development spending by local polity

Note: The figure shows the smooth local polynomial of local income and local development spending against the share of the largest ethnic group in the population for each type of local polity in 1997 and 2007

Political implications

The obvious question is why voting communities may be more entrepreneurial and geared towards greater development. First, we find that the likelihood of leader turnover is significantly higher in voting relative to consensus-building communities. A greater chance of leader turnover in voting communities could be an obvious mechanism to make leaders more entrepreneurial and accountable to their voters. Further, ethnically diverse voting communities are found to be less economically unequal, thus less prone to elite capture.

Although we focus on Indonesia, it is not a unique example in this regard. The findings from our research hold significance for numerous countries, including India and those in the west. It is important to bear in mind that growing immigration could be a particular threat to community homogeneity that may challenge social harmony and integration. For instance, in recent years, there has been an increase in public apprehension in the UK about the perceived threat posed to ‘British identity’ by immigration2, which was partly responsible for the Brexit referendum outcome. This sentiment has bolstered anti-immigration policies with little impact on level of immigration though, ignoring the urgent need to effectively integrate migrants into their new societies. Immigration works only when integration works. Dysfunctional decentralisation systems may jeopardise effective integration and thereby explain some of the crises of democracy in the world today. Making these systems operational and effective has possibly never been more important.

Notes:

1. Propensity score matching (PSM) is a quasi-experimental method in which statistical techniques are used to construct an artificial control group by matching each treated unit with a non-treated unit of similar characteristics. A successful implementation of PSM methods requires that the treatment and control groups are comparable in terms of all observable covariates. The idea is to compare communities that have a very similar probability of receiving the treatment (similar propensity score) based on some observables, but where some localities received the treatment while others did not. Thus, for a given propensity score, the exposure to treatment is random and therefore the treated and control units should be observationally identical.

2. A study by Wadsworth et al. (2016) observed that many people are worried about the growing level of immigration into the country and believe that this immigration has already impacted their quality of life, wages and UK job prospects. Growing anti-immigration opinions are not isolated to the UK; many European countries and their citizens exhibit anti-immigration beliefs to a degree (Card et al. 2005).

Further Reading

- Card, D, C Dustmann and I Preston (2005), ‘Understanding attitudes to immigration: The migration and minority module of the first European Social Survey’, CReAM Discussion Paper No 03/05. Available here.

- Mansuri, G and V Rao (2013), “Localizing Development: Does Participation Work?”, Policy Research Report, World Bank.

- Mitra, A and S Pal (2023), ‘How does fiscal decentralisation affect local polities? Evidence from local communities in Indonesia’, in J-P Faguet and S Pal (eds.), Decentralised Governance: Crafting Effective Democracies Around The World, LSE Press, London.

- Ghosh, S, A Mitra and S Pal (2023), ‘Does Minority Representation Promote Spending for Social Cohesion? An Analysis of Local Governments in Three English Cities’, University of Surrey.

- Wadsworth, J, S Dhingra, G Ottaviano and J Van Reenen (2016), ‘Brexit and the Impact of Immigration on the UK’, CEP Brexit Analysis No. 5, Centre for Economic Performance.

13 October, 2023

13 October, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.