Women as citizens show up and speak up less in political spaces than men across the globe, particularly in lower- and middle-income countries. This article studies the persistent gender gap in political participation in Madhya Pradesh, India and finds that the reason for this is not simply the unequal distribution of resources, inefficient household division of labour, or gender-exclusionary institutions, but their combination along with social norms that preclude women’s extra-household political networking.

Women around the globe, but particularly in many developing contexts, remain absent and invisible in political institutions and dialogue. As of 2015, women’s suffrage in democracies was nearly universal and more than 130 countries had gone so far as to implement political quotas for women (Hughes et al. 2019). Gender quotas, for example, have been shown to increase women’s representation, shift policy towards women’s interests, and improve gender equality along other dimensions (Lott and Kenny 1999, Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004, Miller 2008, Beaman et al. 2009, Catalano 2009, Ford and Pande 2011, Clayton and Zetterberg 2018).

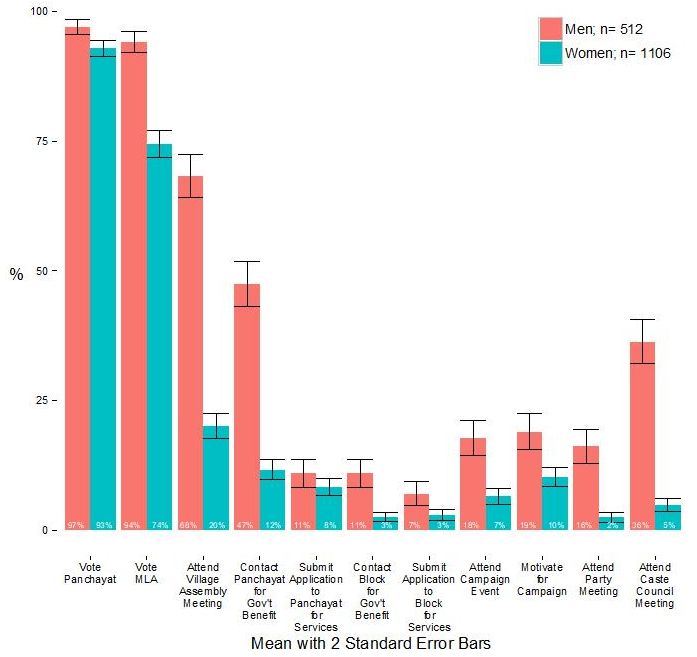

Yet women as citizens show up and speak up less in political spaces than men across much of the globe and particularly in lower- and middle-income countries. Figure 1 depicts this stark gender gap. In 2016, I conducted a survey with 5,371 women and 2,399 men in rural Madhya Pradesh and found that on average men were 50 percentage points more likely to say that they had attended a village assembly meeting and 30 percentage points more likely to have contacted the local leader. Moreover, this gender gap in political behaviour is orders of magnitude larger that the caste gap in political behaviour, which has been the focus of much research. Representative survey data from all of India shows that the average attendance rates at village assembly meetings range from 25-33% for men and 6-11% for women across five caste sub-categories (Desai et al 2011), revealing that participatory differences across caste are much less distinct than differences across gender.

Figure 1. The gender gap in political participation in rural Madhya Pradesh

Notes: MLA stands for Member of Legislative Assembly. Standard error is a measure of precision of the sample mean (average).

Our understanding of gendered inequalities in political participation derives in large part from research on high-income democracies (Brady, Verba and Schlozman 1995, Inglehart and Norris 2000, Burns, Schlozman and Verba 2001, Iversen and Rosenbluth 2010, Karpowitz and Mendelberg 2014). Seminal theories focused on explaining individual-level political behaviour begin from the premise that access to resources – money, education, and time – conditions the costs of political engagement. The gender gap in political participation, therefore, is argued to be the result of a gender gap in resources (Brady, Verba and Schlozman 1995, Burns, Schlozman and Verba 2001). Women, to a greater degree than men, have not accumulated the political and non-political resources necessary to reduce the informational and physical costs to political participation. The implication is that, as resources equalise, so does political participation.

Alternative traditional political economy models, as argued principally by Becker (1981), have focused on the household instead of the individual and explain women’s lack of participation as the efficient outcome of the household division of labour. In this model, women bear the responsibility for the household because of a marginal advantage in childcare and corresponding socialisation patterns. Households’ interests are therefore perfectly aligned and households behave as unitary actors. One implication of this model is that this economic division of labour could also generate a political division of labour with men representing the household’s interests in political spaces because of greater access to relevant resources and subsequent lower costs of participation.

The present experiences of women in low- and middle-income democracies pose a challenge to these models of political behaviour: while women’s political participation remains below that of men, it varies importantly within and across countries. For example, in the specific case of India, women’s political participation remains low on average but grassroots women’s movements have emerged and effectuated important political change. A notable example is the Gulabi Gang in India, an informal group of women in North India known for their pink Saris that have fought to reduce domestic violence and have become a political force to be reckoned with.

How can we explain the persistently low political participation of women across many developing countries while accounting for the growing number of contradictory cases?

To begin, several relevant facts must be incorporated into models of gendered behaviour in developing countries. First, even in regions where divorce is rare and a strong economic division of labour persists, intra-household preferences often diverge (Gottlieb et al. 2016). In recent work, I have argued and demonstrated how gendered preference differences can emerge from the economic division of labour itself (Artiz Prillaman 2018). Take, for example, the public provision of water. While the entire household benefits from the provision of water, women, in their role as household caretaker, bear the responsibility for the collection of water. They, therefore, have a greater stake in the quality and location of water provision than their husbands and are more likely to prioritise the provision of water in their political demands. Intra-household preference differences can also derive from gender-specific experiences (for example, violence against women) or simply because women have a desire to increase gender equality.

Second, gender gaps in political preferences often go hand in hand with gender gaps in political participation. Women may remain absent from political spaces even if their preferences are underrepresented in those spaces. Recent work by Sarah Khan (2017) shows that women are more likely to prioritise their husband’s preferences, especially when the intra-household preference differential is large. These first two conclusions suggest the need for a model that can explain household coordination but allow for intra-household variation in preferences.

Third, while resource stocks may correlate with political participation and may even be a necessary condition for political participation, removing the gap in resources alone is unlikely to induce women’s political participation (Desposato and Norrander 2009, Gottlieb 2016). For example, using original survey data from six districts in Madhya Pradesh in 2016, I find that 86% of the gender gap in political participation is left unexplained by differences in resources (education, labour market participation, free time, voluntary activity, and civic skills) (Artiz Prillaman 2018).

The importance of social connection

Motivated by these facts and the variation in women’s political participation in India, in a recent paper (Artiz Prillaman 2018), I study the case of rural Madhya Pradesh to ask why most women remain absent from political spaces. My theoretical model centres on the household and the nature of political coordination in patrilocal, non-nuclear families, arguing that most households will coordinate their political behaviour and behave as a unitary actor. This creates a household political division of labour, where men act as the political agent of the household and vocalised household preferences skew in favour of men’s interests.

Why would women coordinate their political behaviour with that of the household? I argue that the degree of women’s social isolation/social connectedness shapes their capacity to coordinate their political behaviour outside the household. Gender-biased social norms limit women’s role outside of the household (Chhibber 2002). Often the woman’s space is seen as the house whereas men have the freedom to engage in community institutions, and politics in particular is seen as a man’s space. This division is enforced with substantial mobility constraints: 72% of women in a representative survey from India reported having to ask permission to visit a friend or family member in their village and 23% said that even if granted permission they would not be allowed to go alone (Desai et al. 2011). All of this is enforced through a fear of backlash, often through social sanctions, and even violence.

This political division of labour, therefore, under-represents women’s interests and suppresses women’s voice as a result of disparities in economic bargaining power, intra-household resources inequalities, and gender-biased social norms, creating a system of gender-based insiders and outsiders in politics.

When women’s social networks, however, shift in such a way as to include more women, women’s political participation is likely to increase. To test this relationship, my research conducted in Madhya Pradesh leveraged a natural experiment that created as-if random variation1 in exposure to an NGO (non-governmental organisation) programme aimed at mobilising women into Self-Help Groups (SHGs). SHGs are informal associations of 10 to 20 women from the same village that act as informal savings and credit institutions. SHGs meet frequently and non-members are not allowed at these meetings. As a result, SHGs give women access to economic networks of only other women. Participation in these SHGs yielded substantial increases in women’s non-voting, local political participation: women that had participated in an SHG were twice as likely to attend village assembly meetings or make a claim on local leaders. Data, along with corroborating interview evidence, suggests that this positive effect is largely the result of women’s coordinated collective action to jointly demand representation and combat backlash from men. I also find suggestive evidence that SHG participation helped to build women's political knowledge, confidence, and civic skills by providing them with a space to experiment with their political voice (Artiz Prillaman 2018, Artiz Prillaman 2019, Parthasarathy et al. 2017).

Women’s representation as citizens in political spaces is important on normative grounds of political inclusion and on political economy grounds because it is likely to cause policy change. We know that when women enter politics, policy changes. In India, women’s representation in local elected offices increased the provision of certain public goods (Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004). In Latin America, women’s political movements have yielded the greatest impacts on policies aimed at combating violence against women (Htun and Weldon 2012). And in sub-Saharan Africa, women’s representation in national office is associated with greater political engagement by women (Barnes and Burchard 2013). Yet, our understanding of women’s decisions to participate in politics has for a long time failed to recognise that the constraint to doing so is not simply lack of resources, a household division of labour or the rules of divorce, but the combination of all of these with social norms that preclude extra-household political networks. Once we recognise this, it becomes possible to explain and respond to the persistent gender gap in political participation across developing democracies.

Notes:

- Often it is not possible or inefficient to randomise variables that we care about, such as the structure of people’s social networks. However, looking simply at the relationship between people’s social networks and their political behaviour could be misleading. People who are actively engaged in politics are likely to choose social networks very different from those who are not actively engaged. To understand how the same type of person would behave with different social networks but without randomisation, we can attempt to identify natural experiments. These are observational studies where some factor of the study allows for arguably random assignment of people to the variable we care about. In this case, the way that the NGO determined which villages would receive their programme was arbitrary and not a function of underlying levels of political participation.

Further Reading

- Artiz Prillaman, S (2018), ‘Strength in Numbers: How Women’s Groups Close India’s Political Gender Gap’, Working paper.

- Artiz Prillaman, S (2019), ‘Is Knowledge Power?: Civics Training, Women’s Political Representation, and Local Governance in India’, Working paper.

- Barnes, Tiffany D and Stephanie M Burchard (2013), “Engendering’ politics: The impact of descriptive representation on women’s political engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa”, Comparative Political Studies,46(7): 767-790.

- Beaman, Lori, Raghabendra Chattopadhyay, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande and Petia Topalova (2009), “Powerful women: does exposure reduce bias?”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics,124(4): 1497-1540.

- Becker, Gary S (1981), “Altruism in the Family and Selfishness in the Market Place”, Economica, 48(189): 1-15.

- Brady, Henry E, Sidney Verba and Kay Lehman Schlozman (1995), “Beyond SES: A resource model of political participation”, American Political Science Review, 271-294.

- Burns, N, KL Schlozman and S Verba (2001), The private roots of public action, Harvard University Press.

- Catalano, Ana (2009), “Women acting for women? An analysis of gender and debate participation in the British House of Commons 2005–2007”, Politics & Gender,5(1): 45-68.

- Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra and Esther Duflo (2004), “Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India”, Econometrica,72(5): 1409-1443.

- Chhibber, Pradeep (2002), “Why are some women politically active? The household, public space, and political participation in India”, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43(3-5): 409-429.

- Clayton, Amanda and Pär Zetterberg (2018), “Quota Shocks: "Electoral Gender Quotas and Government Spending Priorities Worldwide”, The Journal of Politics, 80(3): 916-932.

- Desai, S, R Vanneman and National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) New Delhi (2011), Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS-II), 2011-12, ICPSR 36151-v2, Inter-university Consortium for Political Science and Research, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 31 July 2015.

- Desposato, Scott and Barbara Norrander (2009), “The Gender Gap in Latin America: Contextual and Individual Influences on Gender and Political Participation”, British Journal of Political Science, 39(1): 141-162.

- Ford, D and R Pande (2011), ‘Gender quotas and female leadership: A review’ Background paper for the world development report on gender’.

- Gottlieb, Jessica (2016), “Why might information exacerbate the gender gap in civic participation? Evidence from Mali”, World Development, 86: 95–110.

- Gottlieb, Jessica, Guy Grossman and Amanda Lea Robinson (2016), “Do Men and Women Have Different Policy Preferences in Africa? Determinants and Implications of Gender Gaps in Policy Prioritization”, British Journal of Political Science, 1–26.

- Htun, Mala, and S Laurel Weldon (2012), “The civic origins of progressive policy change: Combating violence against women in global perspective, 1975–2005”, American Political Science Review,106(3): 548-569.

- Hughes, Melanie, Pamela Paxton, Amanda Clayton and Pär Zetterberg (2019), “Global Gender Quota Adoption, Implementation and Reform”, Comparative Politics.

- Inglehart, Ronald and Pippa Norris (2000), “The developmental theory of the gender gap: Womens and mens voting behavior in global perspective”, International Political Science Review, 21(4): 441–463.

- Iversen, Torben, and Frances McCall Rosenbluth (2006), “The Political Economy of Gender: Explaining Cross-National Variation in the Gender Division of Labor and the Gender Voting Gap”, American Journal of Political Science, 50(1): 1-19.

- Iversen, T and F McCall Rosenbluth (2010), Women, work, and politics: The political economy of gender inequality, Yale University Press.

- Khan, S (2017), ‘Personal is Political: Prospects for Women's Substantive Representation in Pakistan’, Working paper.

- Kitschelt, Herbert and Steven I Wilkinson (eds.) (2007), Patrons, clients and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition, Cambridge University Press.

- Lott, Jr, John R and Lawrence W Kenny (1999), “Did women's suffrage change the size and scope of government?”, Journal of political Economy, 107(6): 1163-1198.

- Miller, Grant (2008), “Women's suffrage, political responsiveness, and child survival in American history”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3): 1287-1327.

- Parthasarathy, R, V Rao and N Palaniswamy (2017), ‘Unheard voices: the challenge of inducing women's civic speech’, Policy Research working paper no. WPS 8120, The World Bank, Washington DC.

- Sinclair, B (2012), The social citizen: Peer networks and political behavior, University of Chicago Press.

- Stokes, Susan C (2005), “Perverse accountability: A formal model of machine politics with evidence from Argentina”, American Political Science Review,99(3): 315-325.

15 April, 2019

15 April, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.