Women’s political candidacy in India is very low and appears to be an important barrier to their representation in government. Does a deficiency of female role models hold back women’s candidacy? Analysing data from state elections during 1980-2007 in India, this column reports no entry of new women candidates following a woman’s electoral victory, and a decline in entry in states with an entrenched gender bias.

Raising the share of women in government has been shown to result in policy choices that more effectively represent the interests of women and children. Having more women in Indian state legislatures leads to improvements in infant mortality rates (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras 2014) and primary school completion (Clots-Figueras 2012); women are less corrupt as politicians in Brazil (Brollo and Troiano 2015) and extending the franchise to women in early twentieth century America led to sharp reductions in infant mortality (Miller 2008). Other studies find, in India and other countries, that electing women to political office changes spending priorities towards domains preferred by women (Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004), and results in greater reporting of crimes against women (Iyer et al. 2012).

While women’s participation as voters falls short of that of men, the gap has been narrowing: in India’s state assembly (Vidhan Sabha) elections women’s voter turnout was 54.6% compared to 64.1% for men in 1980-1984, but it was only 0.8 percentage points lower in 2008-2013. In fact, more women than men turned out to vote in nine of India’s states and Union Territories during the Lok Sabha1 elections of 2014. Despite this, women remain severely under-represented as legislators. While their share has increased from 4% in 1980-1984 to 8.3% in 2008-2013, it is small. Averaging over 1980-2007, women comprised 5.5% of state legislators. A striking but seldom discussed fact is that only 4.4% of all candidates for state assemblies in this period were women2. So, conditional upon contesting, women exhibit somewhat stronger chances of winning than men, and women’s candidacy emerges as a potentially critical barrier to their eventual representation in government.

Female role models and women’s political candidacy

What might hold back women’s political candidacy? A deficiency of female role models has often been proposed as a reason for the persistence of gender gaps in leadership positions in the corporate or university sectors, although there is limited rigorous evidence of how much this matters (Bertrand et al. 2014, Lawless and Fox 2010, Pande and Ford 2012). We investigated this in the political arena, testing whether the demonstrated electoral success of women results in more women candidates contesting in subsequent elections (Bhalotra, Clots-Figueras and Iyer 2015).

In general, if we observe a higher probability that women contest or win in a constituency previously won by a woman, this may reflect differences between constituencies which elect women and those that elect men. For instance, in places where women win, voters might be more woman-friendly or more progressive and if these characteristics persist over time then women will be more likely to win in successive elections. So as to identify causal effects of women’s electoral victory independently of voter preferences, we compare electoral constituencies in which a woman won narrowly against a man to those in which a man won narrowly against a woman. The premise is that the identity of the winner in close elections is quasi-random rather than a reflection of the preferences of the electorate. So, in areas with mixed-gender close elections, those in which a women wins are very similar to those in which a man wins, and the event of a woman winning effectively becomes similar to a ‘natural experiment’, the causal effects of which can be identified3.

Women’s electoral victory does not encourage new women to contest

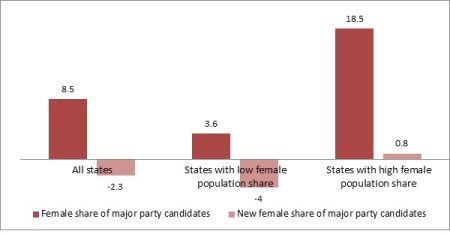

Using constituency data covering all state elections in 1980-2007, we find that a woman winning leads to an 8.5% increase in the share of women candidates in the next election, but that this is driven primarily by an increased propensity of the incumbent woman to re-contest. The incumbent effect is non-trivial in India where 34% of female incumbents and 28% of male incumbents do not contest for re-election despite there being no term limits. There are no spillover effects of observing a woman’s victory: other parties do not switch to fielding women candidates, and there is no increase in female candidacy in nearby constituencies.

Importantly, we find no evidence that new women are encouraged to contest. In fact, in the northern and western states, where gender bias is known to be deeply entrenched, a woman’s electoral victory is followed by a significant decline in the share of new women candidates in the next election (see Figure 1 where gender bias is proxied by the share of women in the population; we find similar results when we proxy gender bias by the male-female literacy differential instead). Consistent with backlash or an intensification of bias against women following women’s electoral victory, we find that the decline in new women candidates is larger among parties headed by men, and that there is also a decline in the chances of a woman winning. This coheres with some previous evidence of male backlash against women performing non-traditional roles or earning more (Mani 2011, Gagliarducci and Paserman 2012, Gangadharan et al. 2014). In sharp contrast, in states with lower levels of entrenched gender bias, a woman is more likely to win the next election, although there is no significant change in the share of new women candidates.

Figure 1. Effect of a female electoral victory (in percentage points)

Note: The first panel shows that in India, on average, there is an 8.5% increase in the share of women candidates in constituencies from which a woman won a seat in the state legislative assembly in the previous election, but a 2.3% decrease in the share of new women candidates. So the increase is driven by incumbent women being more likely to re-contest than incumbent men. The other two panels show that these results vary with the extent of historical gender bias in the region. Following Sen (2003), we divided the sample into states with a female population share below the median level (indicating high gender bias), and states with a female population share above the median level (indicating lower gender bias). The results show that the negative new candidate entry effect emerges from the more gender-biased states and also that, in these states, the positive incumbency effect is smaller.

Note: The first panel shows that in India, on average, there is an 8.5% increase in the share of women candidates in constituencies from which a woman won a seat in the state legislative assembly in the previous election, but a 2.3% decrease in the share of new women candidates. So the increase is driven by incumbent women being more likely to re-contest than incumbent men. The other two panels show that these results vary with the extent of historical gender bias in the region. Following Sen (2003), we divided the sample into states with a female population share below the median level (indicating high gender bias), and states with a female population share above the median level (indicating lower gender bias). The results show that the negative new candidate entry effect emerges from the more gender-biased states and also that, in these states, the positive incumbency effect is smaller. Institutionalised barriers to entry

We investigated whether our results might be explained by a shortage of potential women candidates. We exploit a massive quasi-experimental increase in the share of women in village and district government, created by the implementation of the 1993 Panchayati Raj constitutional amendment, which reserved one-third of seats in village and district councils for women. We do not find larger candidacy responses to women’s electoral victory at the state level after this change was implemented, so it seems that a shortage of potential women candidates cannot explain our results.

We then examined whether the candidacy dynamics we document are unique to women or whether they are also evident for Muslims who are another politically under-represented group in India (Bhalotra et al. 2014). The results for Muslims are strikingly similar to the results for women candidates: there is no entry of new Muslim candidates following a Muslim’s electoral victory, and this response is more negative in states in which Muslims are relatively disadvantaged. This suggests that gender-specific constraints (such as family commitments or women’s lesser willingness to compete: see Lawless and Fox (2010) and Niederle (forthcoming)) are unlikely to be driving our results for women. Instead, the fact that the competitive election of women or Muslims to state assemblies does not stimulate significantly greater candidate entry in these groups would appear to reflect institutionalised barriers to entry.

Overall, our findings indicate that gender bias in society, which may be couched in party leaders, contributes to limiting the play of role model effects for women in politics. Explicit policy initiatives are therefore needed to stimulate entry of new women into the political arena.

Notes:

- Lok Sabha is the lower house of the Parliament of India.

- Statistics in this paragraph are based on data from the Election Commission of India.

- A natural experiment is an empirical study in which individuals exposed to the experimental and control conditions are determined by nature or by idiosyncratic factors such that the process governing exposure resembles random assignment. In this case, the experimental condition of interest is that a woman wins a seat in the state legislative assembly.

Further Reading

- Bertrand, M, S Black, S Jensen and A Lleras-Muney (2014), ‘Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Board Quotas on Female Labor Market Outcomes in Norway’, NBER Working Paper No. 20256, June.

- Bhalotra, S, I Clots-Figueras and L Iyer (2015), ‘Path-Breakers? Women’s Electoral Success and Future Political Participation’, Harvard Business School, Working Paper 14-035.

- Bhalotra, Sonia and Irma Clots-Figueras (2014), “Health and the Political Agency of Women”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 6(2), pp. 164-97, May 2014.

- Brollo, F and U Troiano (2015), ‘What Happens When a Woman Wins an Election? Evidence from Close Races in Brazil’, University of Warwick, Mimeo.

- Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra and Esther Duflo (2004), “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India”, Econometrica, 72(5): 1409-1443.

- Clots-Figueras, Irma (2012), “Are Female Leaders Good for Education? Evidence from India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(1), 212-44.

- Gangadharan, L, T Jain, P Maitra and J Vecci (2015), ‘Social Identity and Governance: The Behavioral Response to Female Leaders’, Monash University, Mimeo, May.

- Iyer, Lakshmi, Anandi Mani, Prachi Mishra and Petia Topalova (2012), “The Power of Political Voice: Women´s Political Representation and Crime in India", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(4), pp. 165-193, October 2012.

- Lawless, Jennifer L and Richard L Fox. (2010), It Still Takes A Candidate: Why Women Don´t Run for Office, New York: Cambridge University Press

- Mani, A (2011), ‘Mine, Yours or Ours: The Efficiency of Household Investment Decisions -- an Experimental Approach’, University of Warwick, Working Paper.

- Miller, Grant (2008), “Women´s Suffrage, Political Responsiveness, and Child Survival in American History”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3): 1287-1327, 2008.

- Niederle, M, ‘Gender’, In Kagel, J and Alvin E Roth (Eds.), Handbook of Experimental Economics, Second Edition, Forthcoming.

- Pande, R and D Ford (2012), ‘Gender Quotas and Female Leadership: A Review’, Background paper for the World Development Report on Gender.

- Sen, Amartya (2003), “Missing women—revisited”, British Medical Journal, 327:1297.

14 September, 2015

14 September, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.