Since large-scale expansions in education impact both individual behaviours and labour markets, convincing causal estimates of their overall benefits are hard to generate. Analysing the overall economic consequences of the District Primary Education Programme in India, this column finds that more educated individuals earned substantially more. However, since others were also receiving more education, this stymied the increase in individual earnings and had significant distributional consequences.

Large-scale educational expansions represent substantial investments of public resources and benefit households by increasing education levels, and therefore productivity in the local economy. However, since they impact both individual behaviour and labour markets, convincing causal estimates of their overall benefits are hard to generate. While small-scale, carefully controlled, researcher-led experiments provide promising evidence about which educational investments are effective (Banerjee et al. 2007), for a variety of reasons these estimates may not be valid for large-scale policies. Importantly, large-scale education programmes may have sizable general equilibrium (GE) effects in the education sector and the labour market that may either undermine or enhance the effectiveness of the intervention (Heckman et al. 1998). Accurately estimating and understanding these GE effects are therefore crucial to assessing the overall benefits of nationwide investments in education.

Students who get more schooling because of such policies may earn higher wages, but they are not affected in isolation. In the labour market, an expansion in schooling makes skilled workers more abundant and lowers their equilibrium earnings (Card and Lemieux 2001). At the same time, an increase in the size of the skilled workforce may attract capital and technology, benefiting skilled workers (Lewis 2011). These changes to the structure of the local economy will affect benefits to workers by changing the labour market returns to schooling – a parameter that labour economists have been debating for at least the last half century (Mincer 1958). In the education sector, on the other hand, additional public schools may simply crowd-out private schools, diminishing the benefits of schooling expansions. In recent research, I develop a new methodology to causally estimate these GE effects in order to determine the overall economic consequences and benefits of a nationwide education programme in India (Khanna 2016).

Framework

In my paper, I build a new framework to analyse the consequences of a large-scale educational expansion programme in India with an explicit focus on issues that are inherent to nationwide government policies: most importantly the GE effects in the markets for both education and labour. I model firms, households, private and public schools, and I decompose wage changes into the individual returns to schooling and the GE effects.

The policy I study is the District Primary Education Programme (DPEP), which expanded public schooling in half the country by targeting low-literacy regions. It was the Indian government´s flagship scheme in the 1990s and early 2000s, and at that time was the largest programme for primary education in terms of geography, population and funding, suggesting that its effects would be similarly broad. The allocation rules were such that districts that had a female literacy rate below the national average were more likely to receive the programme. I can therefore compare regions on either side of the literacy-rate cutoff to determine the causal impact of the policy. Instead of comparing education and earnings in say, a high-literacy district in Kerala with a low-literacy district in Bihar, this approach allows me to compare districts that are extremely similar.

To support each piece of the GE model, I create a comprehensive dataset that consists of a combination of household surveys (National Sample Survey (NSS)), Census data, enterprise surveys (Annual Survey of Industries (ASI)) and school-level data (from the District Information System for Education (DISE)) covering the period from 1991 to 2010. I then use the data to estimate the returns to education and the GE effects. I do this by exploiting not just the allocation rule, but also the variation in cohort exposure to the policy and skill levels. Younger cohorts can change their educational attainment in response to the policy, whereas older cohorts cannot. Both the young and the old are, however, affected by changes in the labour market skill distribution and the movement of firms. Furthermore, since it is not necessarily easy to replace an older worker with a younger worker, the GE effects on the two cohorts must be estimated separately. The change in the earnings skill-premium for older workers tells me the part of the GE effects that affect all cohorts, whereas the change in skill-premium for younger workers helps me derive the additional impact on younger workers.

Results

I find that the programme increased both education and earnings for students in targeted regions. When I compare regions that just received the programme to those that just missed out on it, I find that there were more new schools and young workers had more education in DPEP regions. Overall welfare increases are driven by reductions in the costs of education and an increase in the overall output of the region. However, GE effects substantially mitigate the rise in labour market welfare. Increases in the supply of educated workers dampened earnings for skilled workers and put upward pressure on the earnings of unskilled workers.

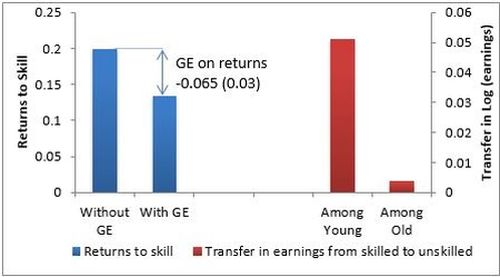

One important component of worker welfare is how much their earnings rise due to acquiring more skill or education. I estimate these returns to skill to be 13.4%, but the labour market GE effects are substantial – they depress the returns by 6.5 percentage points – down from 19.9% – and dampen the increase in student welfare by 23%. These GE effects have important distributional consequences, with a transfer of labour-market benefits from skilled to unskilled workers, particularly among the younger cohorts. High-skill workers who did not change their educational levels under the policy are adversely affected in the labour market, whereas low-skill workers benefit.

Figure 1. Estimated returns to skill and distributional consequences

One crucial concern with an expansion in public schooling is that it may crowd out private supply. On the other hand, a crowd-in could also have occurred if the programme lowered the costs for setting up private schools. Understanding how private schools respond is, therefore, essential to identifying the overall welfare benefits, as a large amount of crowd-out implies that the funds are essentially wasted and could have been spent on other programmes. In my context, I model and estimate this change in private supply, and in line with other work, I find an influx of private schools when public schooling is expanded (Andrabi et al. 2013).

Finally, to track long-run outcomes, I assemble a panel of districts that allows me to follow the local labour and education markets over time. While policies that lower the costs of schooling seem to have positive impacts in the short run, the existing evidence on the persistence of impacts is mixed (Angrist et al. 2006). I find that only a few of the schooling inputs last in the long run. Once the funding is phased out, the physical infrastructure upgrades remain but the differential effects on more qualified teachers dissipates.

The findings in my research indicate that these wage responses may undermine some of the effectiveness of micro-interventions when they are scaled up (Acemoglu 2010). On the other hand, the crowd-in of private schools indicates that large-scale public schooling expansions may have other unintended benefits in the education sector. I also show that once the funding was phased out, certain crucial inputs, like college-educated teachers no longer remain. These empirically important consequences are crucial considerations for both researchers and policymakers who examine or implement such large-scale interventions.

A version of this column first appeared on Development Impact, a blog of the World Bank: http://blogs.worldbank.org/impactevaluations/what-are-schools-worth-depends-general-equilibrium-effects-guest-post-gaurav-khanna

Further Reading

- Acemoglu, Daron (2010), “Theory, General Equilibrium, and Political Economy in Development Economics”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3):17–32.

- Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das and Asim Khwaja (2013), “Students Today, Teachers Tomorrow: Do Public Investments Alleviate Constraints on the Provision of Private Education?”, Journal of Public Economics, 100(1):1–14. Available at https://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/akhwaja/papers/teachersstudentsNov26_2012.pdf.

- Angrist, Joshua, Eric Bettinger and Michael Kremer (2006), “Long-Term Consequences of Secondary School Vouchers: Evidence from an Administrative Records in Colombia”, American Economic Review, 96(3): 847–72.

- Banerjee, Abhijit, Shawn Cole, Esther Duflo and Leigh Linden (2007), “Remedying Education: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments in India”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 22(3): 1235–1264. Available at http://economics.mit.edu/files/9907.

- Card, David and Thomas Lemieux (2001), “Can Falling Supply Explain the Rising Return to College for Younger Men? A Cohort-Based Analysis”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2): 705–746.

- Heckman, James J, Lance Lochner and Christopher Taber (1998), “General Equilibrium Treatment Effects: A Study of Tuition Policy”, The American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 88(2): 381–386. Available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w6426.pdf.

- Khanna, G (2016), ‘Large-scale Education Reform in General Equilibrium: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from India’, Job Market Paper.

- Lewis, Ethan (2011), “Immigration, Skill Mix, and Capital Skill Complementarity”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126 (2): 1029-1069. Available at http://www.dartmouth.edu/~ethang/Lewis2010-web.pdf.

- Mincer, Jacob (1958), “Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution”, Journal of Political Economy, 66(4): 281–302.

01 June, 2016

01 June, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.