Children in India are shorter on average than children in Sub-Saharan Africa, even though Indians are richer on average. What explains this paradox? This column suggests open defecation as a possible explanation, and recommends that policymakers in India should work towards achieving widespread latrine use.

A child’s height is one of the most important indicators of her well-being. Height reflects the accumulated total of early-life health, net nutrition, and disease. Because problems that prevent children from growing tall also prevent them from growing into healthy, productive, smart adults, height predicts adult economic outcomes1 and cognitive achievement2.

Researchers studying height have long been puzzled by a paradox: Among developing countries, differences in average height are not very well explained by differences in income3. In particular, children in India are shorter, on average, than children in Sub-Saharan Africa, even though Indians are richer on average.

What could explain this paradox? Because addressing widespread stunting is a health and economic policy priority, understanding determinants of children’s height is important. In a recent paper, I explore evidence for one possible explanation: open defecation (Spears 2013)4. More than a billion people worldwide defecate openly without using a toilet or latrine. India, with some of the world’s worst stunting, also has one of the very highest rates of open defecation5; more than half of the Indian population does not use any toilet or latrine.

Evidence in the medical and epidemiological6literature has documented that germs in faeces can stunt children’s growth. This may be in part due to diarrhoea, and in part due to enteropathy7- chronic changes in the lining of the intestines8 that make it harder for the body to use nutrients. Studies have also shown a causal link from sanitation to child height. For example, in a paper co-authored with Jeffrey Hammer about an experiment9done in partnership with the World Bank Water and Sanitation Program and the government of Maharashtra, we find that a program that promoted rural sanitation also caused children to grow taller. Therefore, my new paper asks the quantitative, accounting question: how big is the effect of sanitation on child height? Is it big enough to account for important differences?

Open defecation around the world

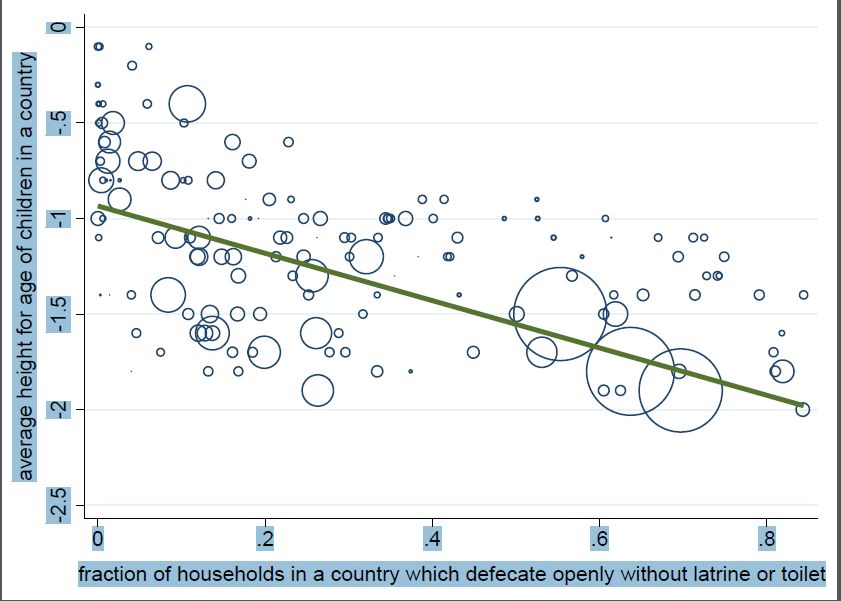

Are the countries where many people defecate openly the same countries where the most children are stunted, and the average child is shortest? Yes, as demonstrated in the graph below. Cross-country differences in sanitation can linearly explain 54 percent of the international variation in average child height.

Figure 1. Open defecation and average height for age of children

Each circle in this graph is a collapsed round of a Demographic and Health Survey; therefore, each represents one country in one year. The size of the circles is proportionate to the population of the country in that year. For example, the three largest circles at the bottom-right of the graph represent India in 1992, 1998, and 2005 – the three years when India had a DHS survey. One striking fact is that India’s circles fall on the trend line. Indian children are very short by international standards, but exactly as short as widespread open defecation in India predicts.

Further analysis in the paper suggests that the association between child height and open defecation is not merely due to some other coincidental factor. It is not accounted for by GDP or differences in governance, female literacy, breastfeeding, immunisation, or other forms of infrastructure such as availability of water or electrification. Because changes over time within countries have an effect on height similar to the effect of differences across countries, it is safe to conclude that the effect is not a coincidental reflection of fixed genetic differences.

One large country not included in the graph above is China: there has never been a Demographic and Health Survey there. However, data on children’s height is available from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. This allows an out-of-sample test of the model’s predictive capability: can the international trend explain child height in China, given its level of open defecation? In fact, the model predicts Chinese height quite accurately. Open defecation rates there are low: less than 4% over the past 20 years, and about 1% now (UNICEF-WHO data). Correspondingly, children are relatively tall among developing countries, with an average height-for-age around -0.791011.

Good toilets make good neighbours

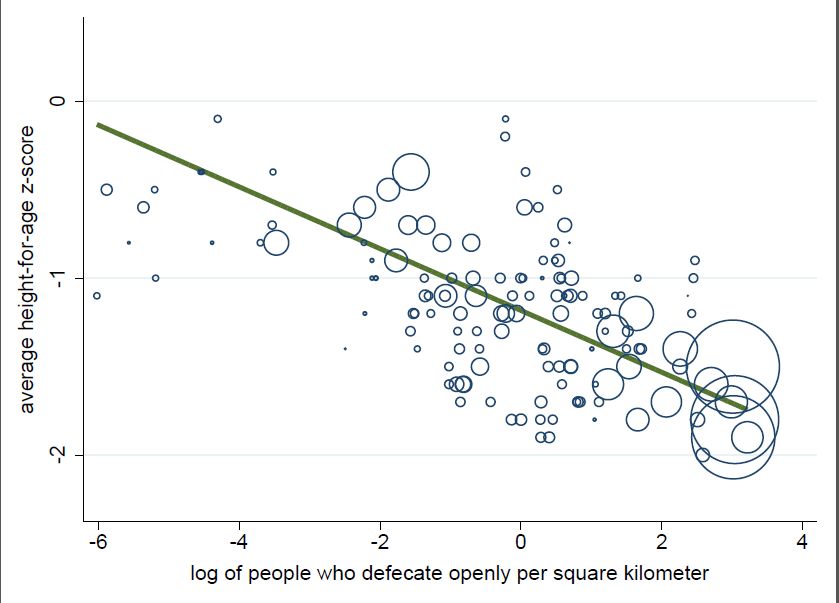

If open defecation is indeed keeping children from growing to their genetic potentials – rather than merely being coincidentally associated with height – we would expect open defecation to be more important for health outcomes where children are more likely to encounter whatever faecal germs are introduced into the environment. This means that population density should matter: living near neighbours who defecate openly is more threatening than living in the same country as people who openly defecate but live far away.

The graph below confirms that this is the case: child height is even more strongly associated with the average number of people per square kilometer in a country who practice open defecation. The density of open defecation per square kilometer, in this simple linear graph, can account for 64% of international variation in child height.

Figure 2. Density of open defecation and average height for age of children

The graph plots the same 140 country years as in Figure 1, and again the three large circles represent India. Once again, stunting among Indian children is no surprise: they face a double threat of widespread open defecation and high population density.

As Alessandro Tarozzi has shown, stunting is common even among relatively well-off families in India (Tarozzi 2008)12. An important part of the story is that open defecation has negative spillovers or “externalities” – economists’ term for when one person’s behaviour impacts other people who have no choice in the matter. This can help explain why even children in the richest households are shorter than the WHO’s international norms for healthy children recommend. They, too, are exposed to faecal germs from the open defecation of nearby households. Indeed, in India’s 2005 DHS survey, the top quintile of children by wealth – and even the top 2.5% – are shorter than healthy growth norms, but are just as tall as the international trend would predict, given the amount of open defecation even in the local areas surrounding where they live.

An “Asian” enigma?

Households in India are less poor, on average, than households in Sub-Saharan Africa, but children there are shorter13. However, widespread Indian stunting is not due to genetics: Indian babies who move to developed countries14in early life grow much taller.

Because of the effect of open defecation on stunting, we can estimate how tall Indian children hypotheticallywould beif exposed to the better sanitation profile in Africa. The paper shows that sanitation differences are sufficient to completely statistically explain this gap. Decomposition results in the paper – in the spirit of Blinder-Oaxaca – show that sanitation differences are able to completely explain this gap15.

This suggests that sanitation is very important, but it isn’t everything important. For example, in joint work with Diane Coffey and Reetika Khera, we show that women’s social rank matters for their children’s height. Other dimensions of inequality are also correlated with height in India: gender, birth order (Jayachandran and Pande 2011)16and caste. It can be simultaneously true that these hierarchies shape heights within India, and that almost all Indian children are shorter than they otherwise would be due to widespread open defecation. Further, because Indian households are richer, Indian children would be expected to be taller than African children, beyond merely eliminating the gap. Moreover, even matching African levels of open defecation, children in both regions would be much too short.

Ending open defecation in India: Next steps for policymakers

Open defecation is everybody’s problem. It is the quintessential “public bad” with negative spillover effects even on households that do not practice it. Because early life health shapes adult cognitive achievement and productivity, ending open defecation is a priority for economic policy and health policy both.

Therefore, officials in Block Development Offices, district Vikas Bhavans, state capitals, and offices in Delhi must make eliminating open defecation a top priority. This means much more than merely building latrines; it means achieving widespread latrine use. Latrines only make people healthier if they are used for defecation. They do not if they are used to store tools or grain, or provide homes for animals, or as a source of repurposable building materials. Any policy response to open defecation must take seriously the thousands of latrines that the government has funded that sit unused (at least as toilets) in rural India. Perhaps surprisingly, in India giving people latrines is not enough.

Stunting is often referred to as “malnutrition”. Sometimes in policy debates, this is taken to imply that the solution is to provide more food. Food is very important, and I look forward to a day when nobody has to feel hungry because they cannot access enough to eat. But what these results suggest is that the disease environment is an important cause of “malnutrition” too. If so, then far from merely a concern of infrastructure specialists, open defecation would a priority for health and nutrition policy – and for children’s well-being and the productivity of the next generation of workers. Talking about “stunting” instead of “malnutrition” when what we really mean is “short children” could clarify discussion and avoid prejudicing policy solutions (Waterlow, 2011)17. If open defecation is, indeed, an important cause of stunting among Indian children, then this could be a step towards taller children who become healthier adults and a more productive workforce.

Notes:

- http://www.princeton.edu/~tvogl/vogl_height.pdf

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570677X11000888

- http://www.pnas.org/content/104/33/13232.abstract

- “How much international variation in child height can sanitation explain?”; available online athttp://riceinstitute.org/wordpress/research/?did=13.

- http://www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/JMP-report-2012-en.pdf

- Branch of medicine that studies patterns, causes and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations

- http://d.yimg.com/kq/groups/13947767/662678642/name/Lancet+Zwitambo.pdf

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22633998

- http://riceinstitute.org/wordpress/research/?did=15

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570677X12000664

- This puts China at the top-left of the graph, near where the trend line touches the vertical axis.

- http://public.econ.duke.edu/~taroz/Tarozzi%202008%20Growth%20References%20India.pdf

- http://www.unicef.org/pon96/nuenigma.htm

- http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/03009739209179285

- This is from decomposition results in the spirit of Blinder-Oaxaca. Constructing a counterfactual sample of children’s heights in India’s most recent DHS weighted to match the exposure to open defecation in a set of pooled DHS surveys from Sub-Saharan Africa can eliminate the India-Africa gap. For more details, please see the paper.

- http://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/jayachandran_final_malnutrition_talk.pdf

- http://www.smith-gordon-publishing.com/pdf/Chapter-1-Reflections-on-stunting-JC-Waterlow.pdf

18 February, 2013

18 February, 2013

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.