Central tax revenues will now be shared among states not just on the basis of population, area, and income, but also forest cover. In this article, Jonah Busch, an environmental economist at the Center for Global Development, contends that the fiscal reform has the potential to become quite a potent climate instrument. It can serve as an example for other countries with similar tax revenue distribution systems and high rates of deforestation.

India just did something big for the climate: it announced that it will allocate US$6 billion a year in tax revenue in a way that will encourage forest conservation. That’s more results-based finance for forest conservation than any other country in the world, including the current biggest spender Norway.

A watershed fiscal reform

Here’s how it will work: every year India’s central government collects about US$200 billion in taxes. From that sum it then passes along about US$60 billion to the 29 state governments. Following recommendations by India’s 14th Finance Commission, Parliament, in February, accepted a watershed reform that not only increases the size of transfers to states from US$60 billion to US$80 billion, but also changes how this tax revenue is distributed between states.

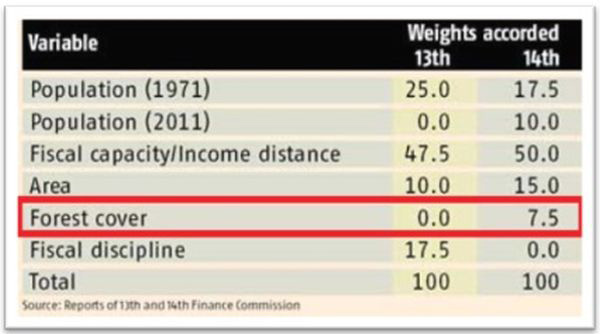

The reform changes the “horizontal devolution” formula so that the pie will now – for the first time – be shared between states not just on the basis of population, area, and income, but also forest cover1.

Table 1. Horizontal devolution formula in the 13th and 14th Finance Commissions

Image Source: Business Standard.

Image Source: Business Standard.

States’ share of tax revenue will now depend on how much forest they have maintained, as monitored by India’s 2013 Forest Survey. When the formula is recalculated in five years, states can expect their share of tax revenue to go up or down based on how much forest they have conserved or replanted. This means that the tax revenue distribution reform is not only a radical transformation of centre-state relations, as my colleague Anit Mukherjee describes; it’s also a big, albeit stealthy, climate move.

Why this matters

Forests are a safe, natural carbon-capture-and-storage system for reducing climate change. Burning one square mile of tropical rainforest emits as much carbon pollution to the atmosphere as driving a typical American car to the sun and back, twice (Seymour and Busch 2014). And forests contribute to cleaner water, more food, more hydroelectricity, and safer towns and infrastructure (see my video below). So when India protects its forests, it protects the climate and promotes development.

And the incentive to protect and restore forests in India just went up — a lot. The amount of tax revenue that will go to Indian states on the basis of forest cover works out to roughly US$6 billion per year. This means that India’s central government just surpassed Norway as the world’s largest results-based funder of forest conservation, by an order of magnitude. Since 2008 the generous Norwegians have offered around US$3 billion total (Norman and Nakhooda 2014) for reducing emissions from deforestation (Reducing Emissions through Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+))2, through international agreements with Brazil (Birdsall et al. 2014) , Indonesia (Seymour at al. 2015), Guyana (Busch and Birdsall 2014), and others. Finance for REDD+ from other rich countries has been lower and slower. India’s impressive financial commitment hardly lets rich countries off the hook for their promised finance for REDD+; rather it raises the bar.

India’s new tax revenue apportionment formula has the potential to become quite a potent climate instrument. India reports that its regrowing forests remove more than 200 million tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year, offsetting about 15% of its greenhouse gas emissions from other sectors. We can expect this number to grow under the new fiscal arrangement.

India’s has around 50 million hectares of forest, so the forest-based revenue transfer works out to about US$120 per hectare per year. That’s a meaningful amount. US$120 per hectare per year is in the neighbourhood of farmers’ potential earnings from agriculture, so it provides economically viable support to states seeking to grow their agricultural output without clearing forests. And US$120 per hectare per year is larger than the payments other countries make through payment-for-ecosystem services (PES) programmes to successfully incentivise individual landowners to conserve forests3.

Furthermore, the new tax revenue distribution formula will coalesce politicians’ and bureaucrats’ attention on forest cover. Shared focus on a single indicator may matter as much or more for success as the financial incentive itself, according to new research on government-to-government performance-based payments by my colleagues Bill Savedoff and Rita Perakis. A US$6 billion pie for forest cover ought to get a lot of politicians’ attention.

Smart tax policy can be smart environmental policy

The tax revenue distribution reform accepted by Parliament recognises climate protection as a public good and fiscal policy as a tool for balancing this public good with economic growth:

“We recognise that States have an additional responsibility towards management of environment and climate change, while creating conditions for sustainable economic growth and development. Of these complex and multidimensional issues, we have addressed a key aspect, namely, forest cover, in the devolution formula. We believe that a large forest cover provides huge ecological benefits, but there is also an opportunity cost in terms of area not available for other economic activities and this also serves as an important indicator of fiscal disability. We have assigned 7.5 per cent weight to the forest cover.”

India has shown that smart tax policy can be smart environmental policy. The gauntlet has been thrown. Countries with similar tax revenue distribution systems and high rates of deforestation, like Indonesia, should look closely at India’s example of fiscal reform as an environmental instrument. And so, for that matter, should the United States: putting a price on carbon using a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system can fight climate change while reapportioning the tax burden more efficiently.

In the meantime, India has just given climate, forests, and everyone who depends on them something big to celebrate.

This article first appeared on the Center for Global Development Blog.

Notes:

- Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India, Arvind Subramanian, explains the reform in detail here.

- Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) is an effort to create a financial value for the carbon stored in forests, offering incentives for developing countries to reduce emissions from forested lands and invest in low-carbon paths to sustainable development.

- Costa Rica pays landowners US$60-80 per hectare per year for forest protection and US$200-300 per hectare per year for forest restoration. Ecuador pays landowners US$10-30 per hectare per year for forest protection; Mexico pays US$27-36 per hectare per year; Vietnam pays about US$15-20 per hectare per year.

Further Reading

- Birdsall, N, W Savedoff and F Seymour (2014), ‘The Brazil-Norway Agreement with Performance-Based Payments for Forest Conservation: Successes, Challenges, and Lessons’, CGD Climate and Forest Paper Series 4, Centre for Global Development Brief.

- Busch, J and N Birdsall (2014), ‘Assessing Performance-Based Payments for Forest Conservation: Six Successes, Four Worries, and Six Possibilities to Explore of the Guyana-Norway Agreement’, CGD Notes, Center for Global Development.

- Mukherjee, A (2015), ‘Power to the States: Is the Indian Model of Fiscal Federalism Taking Shape?’, Global Health Policy Blog, Center for Global Development, 24 February, 2015.

- Norman, M and S Nakhooda (2014), ‘The State of REDD+ Finance’, CGD Climate and Forest Paper Series 5, Center for Global Development Working Paper 378.

- Naqvi, S, K Patidar and A Subramanian (2015), ‘A watershed 14th Finance Commission’, Business Standard, 24 February 2015.

- Seymour, F and J Busch (2014), ‘Why Forests? Why Now? A Preview of the Science, Economics, and Politics of Tropical Forests and Climate Change’, Centre for Global Development Brief.

- Seymour, F, N Birdsall, and W Savedoff (2015), ‘The Indonesia-Norway REDD+ Agreement: A Glass Half-Full’, CGD Policy Paper 56, Center for Global Development.

- Seymour, F (2014), ‘Show Them The Money’, Centre for Global Development Blogs, 16 September 2014

11 May, 2015

11 May, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.