Data collection using face-to-face surveys has faced a roadblock in the wake of restricted mobility and social distancing guidelines to contain the spread of Covid-19. In this post, Coffey et al. describe their experience of conducting a mobile phone survey about social attitudes, discrimination, and public opinion, which has been carried out in seven states and cities in India since 2016.

As the Covid-19 pandemic persists in India and around the world, researchers must find ways to collect data without putting respondents and interviewers at risk. It is hence, an opportune time to describe our experience of conducting Social Attitudes Research, India (SARI) (Hathi et al. 2020) – a mobile phone survey about social attitudes, discrimination, and public opinion that has been carried out in seven states and cities in India since 2016. The goal is to enable other researchers to adapt the survey’s methods to other questions and contexts.

Representative samples and mobile phone surveys

In Statistics 101, students learn the fact that a correctly chosen sample of 1,000 or 1,500 participants can tell us something reasonably accurate about an entire population of millions or hundreds of millions of people. This makes representative sampling an extremely powerful tool for learning about the world.

Yet, most of the survey results that we encounter on a day-to-day basis are not from representative samples. Instead, they may be from a ‘voluntary response’ sample – for example, when a television programme asks viewers to call in and give their opinion on a policy. These convenience-based samples do not allow researchers and policymakers to be confident that the results are true for everyone and not just for the select group who answered the survey.

Do enough people own mobile phones to achieve representative samples?

For many years, researchers remarked that phone surveys could not be used to recruit representative samples in low- and middle-income countries, as they are in rich countries. This is because a large proportion of households in low- and middle-income countries lacked a phone. Yet, with the rapid increase in mobile phone ownership in India, this is changing.

The table below uses data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), 2015 to show the proportion of households in each city/state in which at least one person owns a mobile phone. In the metro cities, household-level mobile phone ownership was nearly 100%. Even in Bihar and Jharkhand, among the poorest states of India, nearly 9 in 10 households had a mobile phone in 2015. These numbers are likely to have increased substantially in the five years since 2015. For instance, in Bihar, where the NFHS data were collected over six months in 2015, households interviewed in the last month of the survey were nearly 4 percentage points more likely to have a mobile phone than households interviewed in the first month.

Table 1. Proportion of households in which at least one person owns a mobile phone

|

% household-level mobile coverage |

|

|

Delhi |

99% |

|

Mumbai |

97% |

|

Rajasthan |

94% |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

92% |

|

Maharashtra |

91% |

|

Bihar + Jharkhand |

89% |

We need new data from face-to-face household surveys to know for certain whether household-level mobile phone coverage in India is now universal, but it is fair to say that it is quite high. In our view, provided researchers follow the sampling strategy outlined below, we no longer expect lack of mobile phone ownership to be a major barrier to constructing high-quality samples in most regions of India.

Respondent selection for a representative mobile phone survey

Respondent selection for SARI begins with random digit dialing designed around the mobile number patterns in India’s telecommunications network. The Department of Telecommunications assigns mobile phone companies five-digit ‘series’ that they are allowed to use at the beginning of the 10-digit mobile phone numbers that they sell. The SARI team generates a sampling frame of potentially active numbers in each ‘mobile circle’ by first creating a list in which series appear in equal proportion to the number of subscribers a company reports to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), divided by the number of series it has1. We then add a randomly generated five-digit number to each series to form a 10-digit mobile number. SARI interviewers call these numbers in random order. Of course, some of the numbers are not active. However, the extra time spent dialing is worthwhile to maximise reach.

Even though nearly every household may have a mobile phone, this does not mean that every adult has one. SARI piloting has shown that older adults and women are less likely to own a mobile phone than younger adults and men. In order to ensure that adults who do not have their own mobile phones are included in the sample, we use within-household respondent selection. The person who answers the phone is asked to list all eligible respondents in the household who do not own a mobile phone – for the purposes of SARI, these are adults aged 18-65 who are the same gender as the interviewer. Survey software, which interviewers also use for recording responses, randomly selects a respondent from the list.

The next step is for interviewers to request to speak to the selected respondent. This step can be difficult and requires substantial training. This is because interviewers must explain to the person who answered the phone why it is important that the survey be done with their family member, rather than with them. Often, interviewers schedule a call-back time to speak to the selected respondent. The SARI team uses a combination of an Excel spreadsheet and an on-paper record to keep track of which numbers and respondents need to be called back and when.

Monitoring sample quality

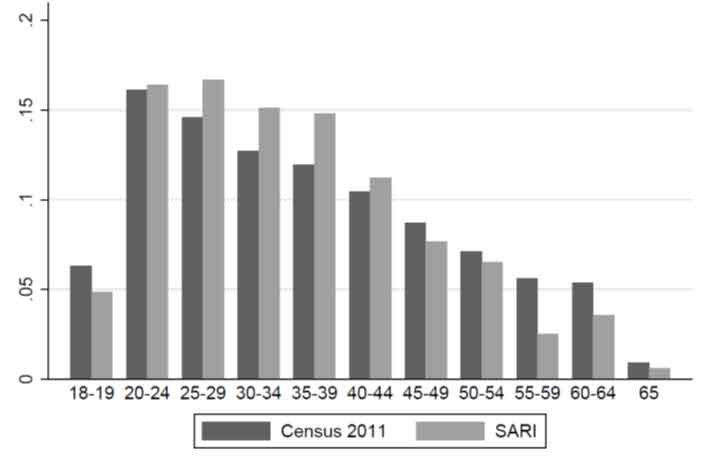

As data are being collected, researchers can track their success towards a representative sample by comparing respondent characteristics to a Census, or other reliable large-scale face-to-face survey. In SARI, the demographic characteristics of respondents are compared to the distribution of Census data on age, education, caste, place (rural/urban), and gender. Figure 1 below provides an example of one such comparison – it shows the distribution of different age categories in the 2011 Census and the SARI sample.2

Figure 1. Distributions of adult ages in the SARI sample from the state of Maharashtra and the 2011 Census

Because individuals from some demographic groups are more likely to respond to the survey than others, SARI uses sample weights that adjust for differential non-response, as is common in survey practice. Still, interviewers are intentional in trying to convince respondents from all education levels, castes, ages, and places to participate. The survey leaders share constructive feedback about the sample composition with the interviewers both as a group and individually. The pay structure of SARI’s surveyors also reflects the emphasis on building a representative sample – they are salaried rather than earning per survey conducted. Paying surveyors on a per-survey basis would give them a financial incentive to interview only the easiest-to-reach respondents.

The need for more survey methods research

Our recent report highlights the challenges and successes of SARI’s attempts to build and learn from representative samples of Indian adults. We hope that as other research teams experiment with phone surveys, they will strive to build representative samples, and share their experiences with others. Unlike in rich countries, where there is a large literature on survey methods, including on survey medium effects, interviewer effects, and question wording and order effects, such research is far less common in India. Yet, it is needed if researchers are to continue to collect accurate information through circumstances such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

This is the first of a three-part series. In the next part (Thursday, 12 November), the authors will discuss how mobile phone surveys can be a valuable medium for incorporating mental health measurement into population-level health surveys.

Notes:

- For example, if out of all of the mobile phone subscribers in a state, 70% of people have phone numbers through Company X, and Company X has 30 series assigned to it from TRAI, then 70% of the phone numbers in SARI’s sampling from will come from Company X’s series, divided evenly among the 30 series.

- More information about SARI’s data quality checks is available in the report.

Further Reading

- Hathi, P, A Thorat, N Khalid, N Khurana and D Coffey (2020), ‘Mobile Phone Survey Methods for Measuring Discrimination’, r.i.c.e and NCAER report.

11 November, 2020

11 November, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.