Given the poor condition of government schools and the perceived efficiency of private schools, Indian parents are increasingly choosing to send their children to private schools. This column examines private school enrolment among 7-18 year olds during 2005-2012 and finds a systematic and pervasive female disadvantage.

Although the Indian Constitution guarantees equal rights for men and women, discrimination against women, continues to be pervasive in different walks of life. As of 2014, India ranks 130 out of 188 countries in terms of the Gender Inequality Index (GII), beating only Afghanistan in South Asia. The Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) is 190 per 1,000 live births; women occupy only around 12% of seats in the Parliament (the women’s reservation bill is pending in the Parliament since 2014); only 27% of women aged 25 or above have at least some secondary education (corresponding figure for men is 57%); and labour force participation rates of women aged 15 years or above is 27% (corresponding figure for men is 80%).

Without the engagement, empowerment, and contribution of women who constitute about 50% of the population, we cannot hope to achieve rapid economic growth or effectively tackle global challenges such as climate change, technology adoption, food security, and conflict. Successive Indian governments have attempted to improve the status of women through policy interventions, the most prominent being the 73rd constitutional amendment to reserve seats for women in village councils, and the modification of Hindu Succession Act to ensure women’s inheritance rights.

Education can empower women, justifying the need to secure ‘education for all’, an essential component of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be attained by 2030. While there is a sizeable literature on discrimination against girls in schooling (see, for example, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), (2012)) and ways to redress it (Meller and Litschig 2016), we know little, if anything, about girls’ access to private schooling in particular. This is especially important in light of the rapid growth of private schooling in India (and indeed around the world) in recent years that has the potential of furthering educational inequality. While about 16% of the villages surveyed in 1996 as a part of the PROBE data had access to private schools, the figure rose to about 28% in 2003 (Muralidharan and Kremer 2006). According to the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) data 24% and 31% of 7-18 year old children attended private school in 2005 and 2012, respectively.

Our knowledge as well as attempt to mitigate gender discrimination in schooling will remain incomplete without a good understanding of the nature and extent of gender discrimination in private schooling. In recent research, we examine the nature of private school enrolment in general, and female disadvantage in private school enrolment among 7–18 year olds (Maitra et al. 2016).

Given the deteriorating state of government schools across India, there have been increasing attempts by policymakers to explore the scope of the private sector to deliver basic education in India (Tooley and Dixon 2003, Tooley 2004). Greater market orientation makes private schools and teachers more accountable to children and parents. Muralidharan (2014) argues that private schools are able to provide the same level of output at approximately one-third the cost.

It is, however, not obvious how this growth in private schools will impact the gender gap in schooling. Private schooling involves fee payment, but also yields additional returns. Gender gap may prevail if returns to private schooling (net of costs) are lower for females. However, it is possible that parents who choose to send their children to private schools may behave in a more altruistic manner, treating boys and girls equally in terms of human capital investment. Further, benefits and costs of private schooling may change differentially for boys and girls as children move from primary to secondary schools as sexual harassment of adolescent girls on way to/from schools become common.

Analysis

We use two rounds of the IHDS data (collected in 2005 and 2012) to explore not only the extent of gender gap in private school enrolment at a given point in time, but also its evolution over time during a period of rapid reforms and steady economic growth in India. We estimate private school enrolment as a function of a child’s gender, birth order, and age group. Given the strong son preference in India, the gender of the child is potentially ‘endogenous’, which means that the same unobserved characteristics of parents may influence both the gender of the child and provision of education opportunities to boys and girls in the household. This is because in India, parents with strong preference for sons continue to have children until they have the desired number of sons (Kishor 1993). This has been worsened by the availability (since the early 1980s) of mechanisms (example, scanning technology) that enable sex-selective abortions (Jha et al. 2011). We attempt to redress this potential bias by exploiting the variation in private school choice among 7-18 year olds born to the same parents within the same household.

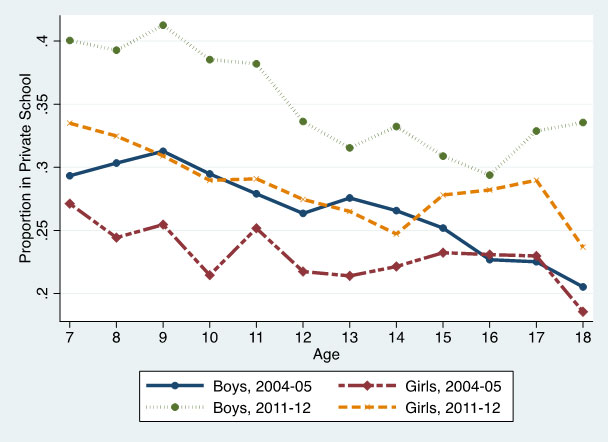

Figure 1 presents the average private school enrolment by age and gender, conditional on any enrolment, for both waves of the data. The period 2005–2012 saw a systematic increase in private school enrolment rate for both boys and girls: private school enrolment rates increased from 27% to 36% for boys and from 23% to 29% for girls. However, the gender difference in private school enrolment increased from 4.1 percentage points (or 17.6% of the average private school enrolment rate for girls in 2005) to 6.7 percentage points (or 23.3% of the average private school enrolment rate for girls in 2012). There is a change in the pattern of gender bias across age groups. For children aged 7–14, the average difference in private school enrolment between boys and girls was about 5 percentage points in 2005 and increased to 7.7 percentage points in 2012. For children aged 15-18, while there was no gender difference in private school enrolment in 2005, the gap increased to 3.7 percentage points in 2012. While the gender gap is statistically significant for the 15–18 year olds in 2012, it is considerably lower than that for children aged 7–14. Possible factors that may explain the lower female disadvantage among 15-18 year olds are: (i) boys drop out of schools to supplement family earnings; (ii) girls’ private school enrolment increases in a bid to protect them from undesirable attention of boys on the street or within school premises.

Figure 1. Enrolment in private school by age, gender and year of survey

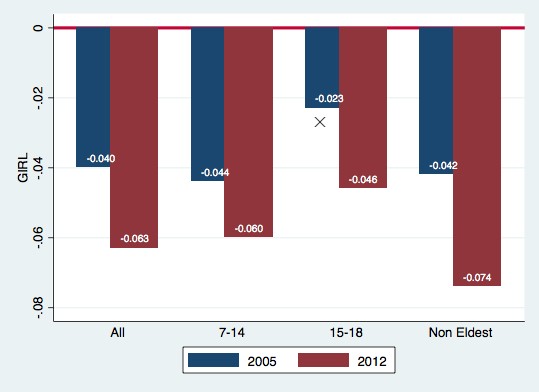

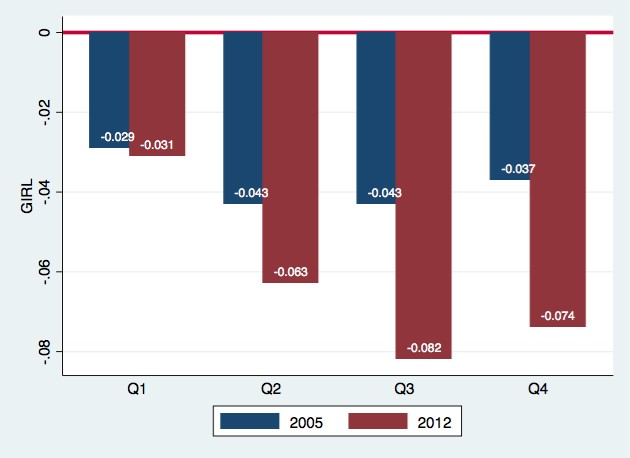

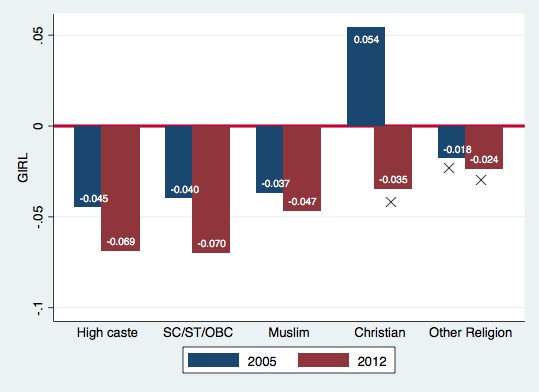

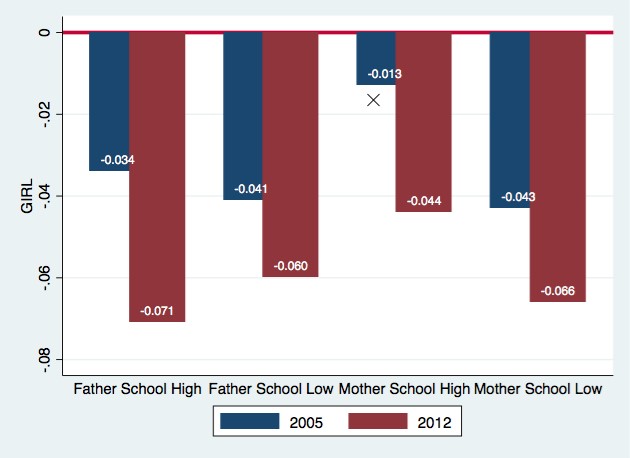

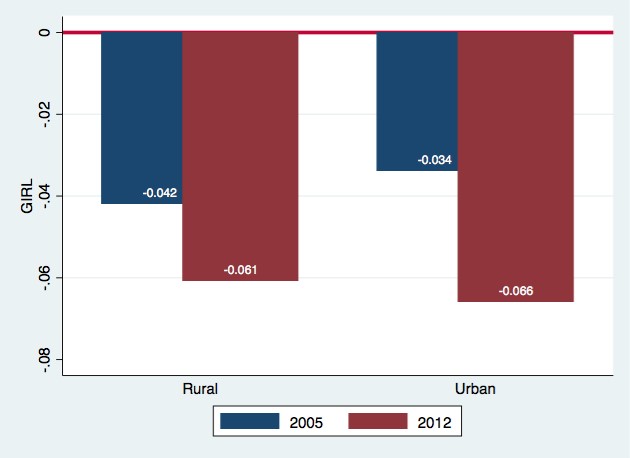

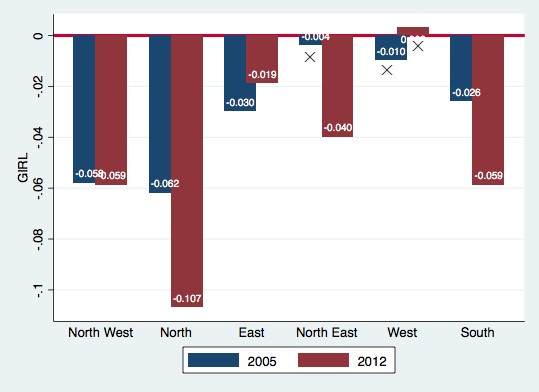

Figure 2 presents the female disadvantage for different sub-samples over the two rounds of the survey: age, expenditure quartile, caste/religion, parental education, sector of residence, and region of residence. While there is considerable variation across the different sub-samples (for example, the extent of gender bias against girls is higher in the north and northwest, in richer households, and in Hindu households), disadvantage against girls is the norm. There is no evidence to suggest that the economic growth and increases in income that the country experienced during the period 2005–2012 has resulted in a move towards more gender equality.

The average female disadvantage was about 4 percentage points in 2005 and this rose to about 6 percentage points in 2012. Indeed, estimates from the sample of the same households observed in both 2005 and 2012 do not indicate any drop in female disadvantage over the period. While we find some variation in the extent of female disadvantage across sub-samples characterised by varying individual, household, and community characteristics, the female disadvantage not only persists but also has worsened in most cases. Thus, there is no denying the fact that female disadvantage in private schooling is real and persistent. The variation in the size of this effect across sub-samples and over time, highlight the non-altruistic nature of preferences: parents tend to balance economic and other socio-cultural considerations (some of which are linked to deep-rooted social values) as boys and girls progress from childhood into adolescence.

Figure 2. Female disadvantage in private schooling, 2005 and 2012

Notes: The 'X' denotes that girls are not significantly worse off compared to boys for the relevant sub-sample.

Policy prescriptions

How does one address the issue of gender bias against girls? Household preferences are often deeply held convictions and are difficult to change in the short run. We need to look at a range of policy options: incentivising school participation at all levels for girls (as in Bangladesh, for example); adaptation of the school curricula to meet girls’ needs, for example, the recruitment of female teachers; adjusting school hours so as to accommodate household chores for girls; ensuring local access to schools and/or transport to and from schools if a local school is not available, especially at the secondary level; and the provision of information about job opportunities for girls. These interventions could go a long way to encourage girls’ schooling. Extending affirmative action policies to ensure girls are enrolled in private schools is also an option worth examining, and incentivising parents to send their daughters to private schools (example, through publicly-funded seat reservation for girls from disadvantaged backgrounds and/or scholarship for meritorious girls) would help in narrowing this gender gap. Clause 12 of the Right to Education (RTE) Act requires private schools to reserve 25% of their seats for students from poor households, being funded by the government. Our analysis highlights the need to extend this affirmative action to focus on girls.

Further Reading

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (2012), ‘Gender Discrimination in Education: The Violation of Rights of Women and Girls’, Global Campaign for Education, Report submitted to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

- Dhawan, H (2016), ‘50% of girls sexually harrased on way to school, 32% stalked: Study’, Times of India, 25 February 2016.

- Jha, Prabhat, Maya Kesler, Rajesh Kumar, Faujdar Ram, Usha Ram, Lukasz Aleksandrowicz, Diego Bassani, Shailaja Chandra and Jayant Banthia (2011), “Trends in Selective Abortions of Girls in India: Analysis of Nationally Representative Birth Histories from 1990 to 2005 and Census Data from 1991 to 2011”, Lancet, 377:1921-1928. Available here.

- Kishor, Sunita (1993), “May God give Sons to All”: Gender and Child Mortality in India”, American Sociological Review, 58(2):247-265.

- Maitra, Pushkar, Sarmistha Pal and Anurag Sharma (2016), “Absence of Altruism? Female Disadvantage in Private School Enrolment in India”, World Development, 86:105-125.

- Meller, Marian and Stephan Litschig (2016), “Adapting the Supply of Education to the Needs of Girls: Evidence from a Policy Experiment in Rural India," Journal of Human Resources, 51(3):760-802.

- Muralidharan, K (2014), ‘Understanding the Relative Effectiveness of Government and Private Schools in India’, Ideas for India, 22 January 2014.

- Muralidharan, K and M Kremer (2006), ‘Public and Private Schools in Rural India’, Mimeo, Harvard University.

- Tooley, James (2004), “Private Education and ‘Education for all’”, Economic Affairs, 24(4):4-7. Available here.

- Tooley, J and P Dixon (2003), ‘Private Schools for the Poor: A Case Study from India’, Discussion Paper, CfBT Research and Development.

07 October, 2016

07 October, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.