Knowing who invests in sovereign debt and how they impact borrowing costs could help governments understand how costly it would be to raise new debt. This article constructs and analyses data on the composition of the investor base for sovereign debt disaggregated into six types of investors for advanced economies and emerging markets. It finds that non-bank investors are most responsive to expansions and changes in the price of sovereign debt, suggesting that understanding their behaviour is crucial to ensure sovereign debt sustainability.

Sovereign borrowing can help buffer an economy from bad macroeconomic shocks. That indebtedness can also make a country vulnerable to financial distress. The sharp global increase in government spending and debt issuance with the Covid-19 pandemic has brought more urgency to understanding how a government can borrow. Answering this question requires knowledge of who invests in sovereign debt and how these investors impact sovereign borrowing costs.

In our recent research (Fang et al. 2023), we tackle this question by building a dataset of the investors in sovereign debt across 95 countries, spanning over 20 years. This dataset decomposes the outstanding debt of each sovereign state into six categories of investors that hold this debt: banks, private non-banks, or official sector lenders (such as the domestic central bank, the IMF, etc.), both domestic and foreign.

Typically, research on sovereign debt focusses on or assumes a specific type of investor. For example, the literature on sovereign default, particularly in emerging markets, focusses on foreign investors, typically modelled as a foreign bank (Eaton and Gersovitz 1981, Arellano 2008). The sovereign-bank nexus literature focusses on domestic banks as investors in sovereign debt (Gennaioli et al. 2014, Fahri and Tirole 2018). A separate literature seeks to understand official sector accumulation of foreign reserves (Ghosh et al. 2017, Bianchi et al. 2018). We use our dataset to jointly study the behaviour and importance of these different investor groups and examine how the composition of the investor base matters. This builds on previous data construction efforts by Arslanalp and Tsuda (2014a, 2014b).

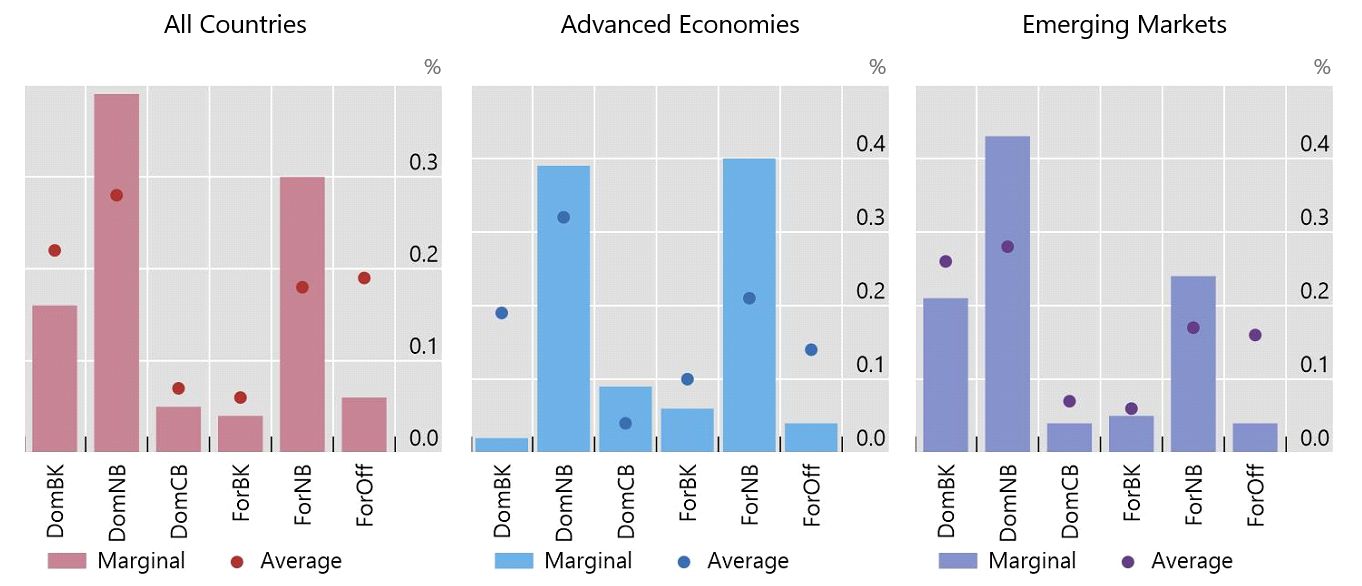

Investment shares of investors in sovereign debt

We first analyse which type of investor is the most marginal – that is, when sovereign debt increases, for which investor does holdings of sovereign debt increase the most? This analysis tells us which investors are the most active players in the sovereign debt market. Second, we examine how responsive each investor group is to changes in the yield on sovereign debt. This helps us understand which investors the sovereign can most readily attract by increasing the price they offer on their debt. We then combine these results to show how the composition of investors affects borrowing costs of the sovereign.

We find that non-banks are the most marginal investor. Despite holding only 46% of the total outstanding sovereign debt on average, non-banks’ holdings account for nearly 70% of the increase (or decrease) in sovereign debt (Figure 1). The prominence is common across both advanced and emerging markets, both within the set of domestic investors and across foreign investors.

Figure 1. Marginal investors in sovereign debt

Source: Fang et al. (2023)

Notes: i) These graphs depict the share of expansions and contractions of sovereign debt, by investor type. From left to right, each graph depicts marginal investment share by: domestic banks, domestic non-banks, domestic central bank, foreign banks, foreign non-banks, and foreign official sector lenders. ii) Average investment is the average share of outstanding debt held by the given investor group.

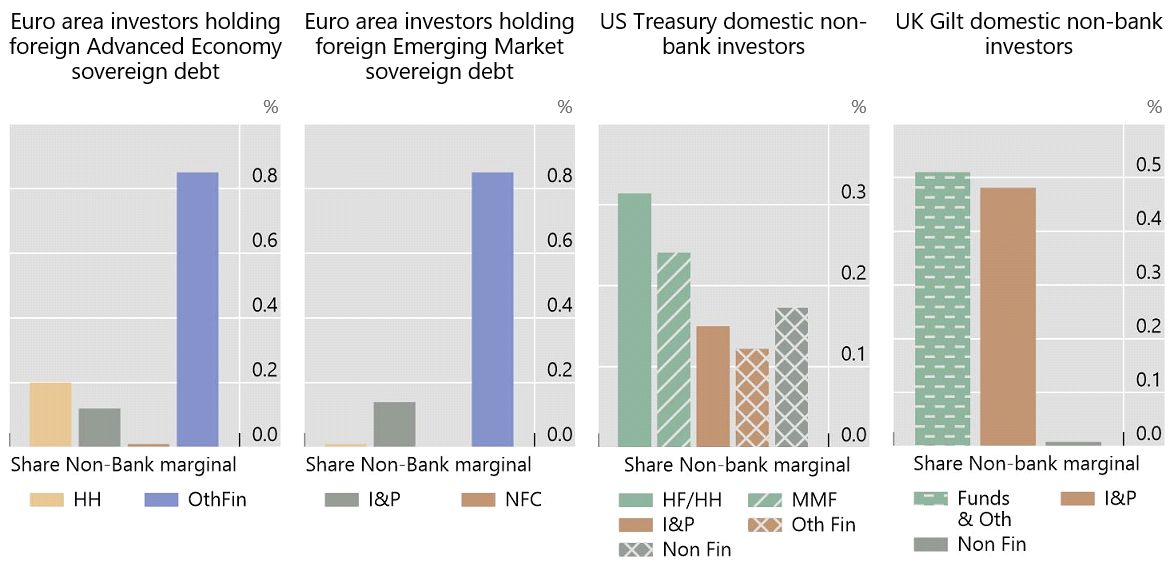

Non-banks are a large and very heterogeneous group of investors. They include money market funds, hedge funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, pension funds, and other non-bank financial companies, as well as non-financial investors such as non-financial corporations and households. To unpack this group, we use granular data on sovereign debt investors from the Euro area, US, and UK. From the Euro area, we examine those investors’ holdings of sovereign debt outside the Euro area (that is, investment by foreign non-banks). For the US and UK, we break down domestic non-banks by the underlying sector and examine holders of US Treasuries and UK Gilts, respectively. Across each of these datasets, the dynamics of non-bank investment in sovereign debt are driven primarily by investment funds. For the Euro area investors, investment funds account for over 80% of the variation in sovereign debt holdings of non-banks , either that of advanced economy or emerging market sovereigns (as seen in the first two panels of Figure 2). In the US, money market funds play a large role, and, along with hedge funds, account for over half of the variation on non-bank treasury holdings (third panel of Figure 2). In the UK, investment funds account for about half of the expansion or contraction in sovereign debt holdings, while insurance companies and pension funds account for the other half (fourth panel of Figure 2). The large influence of the Insurance and Pension (I&P) sector reflects the large share of Gilts they hold. Overall, the low marginal variation in holdings compared to size of outstanding debt held by the I&P sector in both the US (43% of total) and UK (81% of total) are consistent with the typical buy and hold strategies of these investors leading them to be more stable.

Figure 2. Unpacking non-bank investors, by sector

Source: Fang et al. (2023)

Notes: i) Euro area includes investors from those member states of the European Union that have adopted the Euro as their primary currency. ii) These graphs depict the share of expansions and contractions of non-bank sovereign debt holdings, by investor type. In the graphs, “HF/HH” includes hedge funds, private equity, private trusts, and direct household holdings (HH). “NFC” includes non-financial corporations, and similarly “Non Fin” is all non-financial holders excluding households. “I&P” is Insurance and Pension, and “Oth Fin” is all other financial institutions apart from funds and I&P. Similarly, “Funds & Oth” comprises all funds and financial institutions except for I&P.

Responsiveness of investors to sovereign debt yield

Given these findings for who holds sovereign debt, we next consider why this composition matters to borrowers. To do this, we first consider how responsive each investor is to the yield on sovereign debt. Yields (and prices) for government bonds are determined by both supply from sovereign bond issuers and demand from sovereign bond investors. One challenge then is to determine how the investor side changes when the yield changes, holding debt supply constant. We adapt an approach pioneered by Koijen and Yogo (2019, 2020) in order to get a clean estimate of yield changes that are exogenous to the investors.

Our estimates provide striking results that again point to the importance of non-bank investors. Specifically, for both emerging markets and advanced economies, non-bank investors are the creditor group most responsive to changes in yields, especially foreign non-bank investors. In response to a 1% increase in yield, domestic non-banks increase their debt holding by 23%, while domestic banks do so by 12%. Similarly, among the foreign investors, foreign non-banks are the most responsive, as they increase holdings by 38% for a 1% increase in yield.

Lastly, we combine our previous results to assess what these estimates imply for the sovereign borrower, by asking how much the financing cost would increase for a hypothetical debt increase. Our estimates show that a 10% increase in debt corresponds to a 6.7% increase in yield for the average emerging market borrower. However, if non-bank investors are not present and borrowers must borrow from banks, the same 10% increase in debt corresponds to a substantially higher 9.1% increase in yield. Thus, emerging market sovereigns appear highly exposed to the availability of non-bank investor funding.

Conclusion

We conclude that emerging market sovereign investors are highly vulnerable to the presence or absence of non-bank investors. These investors tend to pick up on expansions of sovereign debt and are more price responsive than other investors. This means that sovereigns need to increase the return they offer on their debt by less in order to attract non-banks to hold that debt. With a higher share of non-banks in their investor pool, sovereigns may be able to increase their debt while limiting the costs. Thus, the behaviour of non-bank investors is crucial for understanding sovereign debt sustainability.

This finding does not imply that it would be optimal for sovereigns to have only non-banks in their investor pool. Rather, sovereigns would likely be well served by cultivating a diverse set of investors, one that includes domestic and foreign non-bank investors. Despite the benefits, non-banks can also be more flighty in response to shocks in global markets or in the sovereign’s economy. Thus, their credit could potentially also dry up faster than other investors, and at the exact time when the sovereign needs to raise funds. More detailed and higher frequency data could shed more light on this concern in future research.

As financial conditions continue to tighten, sovereigns will face difficult questions regarding their debt. If the economy takes a turn for the worse, sovereigns can provide an important lifeline. However, this provision often requires increasing their debt to finance spending. Existing debt will also need to be rolled over. Both advanced and emerging market sovereigns will need to monitor their debt issuance closely. Our findings suggest that paying attention to the identities of their investors will give them valuable information about the costs they may need to incur to raise new debt.

Further Reading

- Arellano, Cristina (2008), “Default Risk and Income Fluctuations in Emerging Economies”, American Economic Review, 98(3): 690-712.

- Arslanalp, Serkan and Takahiro Tsuda (2014a), “Tracking Global Demand for Advanced Economy Sovereign Debt”, IMF Economic Review, 62(3): 430-464.

- Arslanalp, S and T Tsuda (2014b), ‘Tracking Global Demand for Emerging Market Sovereign Debt’, IMF Working Paper No. 14/39.

- Bianchi, Javier, Juan Carlos Hatchondo and Leonardo Martinez (2018), “International Reserves and Rollover Risk”, American Economic Review, 108(9): 2629-2670.

- Eaton, Jonathan and Mark Gersovitz (1981), “Debt with potential repudiation: theoretical and empirical analysis”, Review of Economic Studies, 48(2): 289-309.

- Fahri, Emmanuel and Jean Tirole (2018), “Deadly Embrace: Sovereign and Financial Balance Sheets Doom Loops”, Review of Economic Studies, 85(3): 1781-1823.

- Fang, X, B Hardy and K Lewis (2023), ‘Who holds sovereign debt and why it matters’, NBER Working Paper No 30087.

- Gennaioli, Nicola, Alberto Martin and Stephano Rossi (2014), “Sovereign Default, Domestic Banks, and Financial Institutions”, Journal of Finance, 69(2): 819-866.

- Ghosh, Atish R, Jonathan D Ostry and Charalambos G Tsangarides (2017), “Shifting Motives: Explaining the Buildup in Official Reserves in Emerging Markets Since the 1980s”, IMF Economic Review, 65(2): 308-364.

- Koijen, Ralph and Motohiro Yogo (2019), “A demand system approach to asset pricing”, Journal of Political Economy, 127(4): 1475-1515.

- Koijen, R and M Yogo (2020), ‘Exchange rates and asset prices in a global demand system’, NBER Working Paper 27342.

04 August, 2023

04 August, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.