Ever since the RBI switched to flexible inflation targeting with headline Consumer Price Index as the inflation anchor, inflation has witnessed a dramatic collapse. In this article, Renu Kohli contends that volatile food prices have exposed the risks inherent in targeting headline CPI inflation.

Ever since the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) switched over to flexible inflation targeting (FIT), informally from January 2014 and formally in June 2016, inflation has witnessed a dramatic collapse. Inflation based on headline CPI (Consumer Price Index), the new inflation anchor, declined sharply from 8.6% in January 2014 to 1.5% in June 2017, below the lower band of the medium-term target (4%, +/- 2%).

In the historical context of the 28-odd countries that follow inflation targeting (IT) since its introduction in 1989, this scale of achievement is remarkable. One should reckon that most countries switched over to IT regimes only after inflation had stabilised at lower levels, Israel being the rare exception that used IT as a shock policy instrument (see, for example, Bank of England Handbook 29, 2012). India followed a similar path fraught with risks. It is time we commend the RBI and its monetary policy committee (MPC) for spearheading this success. And for those of us who opposed its implementation, it is a moment for reflection.

And yet we observe a general disquiet, some aggressive criticisms on three specific points: (i) inflation has been consistently undershooting RBI’s forecasts; (ii) lower inflation is structural; and (iii) the output gap is large, needing monetary policy support. Thus, the core concern is that RBI’s policy rate has been relatively or even significantly tighter than warranted, hampering a short-term recovery.

It must be flagged that many of the critics have been either vocal or tacit supporters of FIT adopted by the RBI, or at best maintained an ambivalent silence. Their criticisms are not against the IT regime per se or for that matter its operative principles, but directed against the RBI’s inflation forecast errors and the failure of the MPC members to gauge the reality. They seemed dismayed by a five-member majority sticking to their positions, the only comfort being Dr. Dholakia, the lone member who joined their bandwagon, seriously contesting RBI’s projections and significantly differing from the views of fellow members. Who is wrong?

Since the criticisms are directed at practitioners, the RBI and MPC members, and not FIT’s operative principles, it may be fruitful to examine the latter to arrive at some judgement as to what extent the MPC members may be at fault. Now the simplest operative principle of IT is represented by a function familiar as the ‘Taylor Rule’ (Taylor, 1993, 1999) which says the practitioner, that is, the central bank or an institution like the MPC, should take a prior call on the following: (i) the real neutral rate; and (ii) reaction coefficients to inflation and output gap, and transparently communicate these to the market. It should focus on robust inflation and output projections based upon a nominal inflation target and estimates of potential output to arrive at the respective inflation-output gaps. Once this is done, the equation itself works out the nominal policy rate. Even to this date, Professor Taylor believes if too much discretion is allowed to creep in the outcome could turn out to be suboptimal.

But almost all central banks practicing some form of IT strongly disagree. Mr. Bernanke, former chairman, US Federal Reserve, has held that members of MPCs cannot be robots, that is, purely rule-based; they should have the discretion to take calls on both reaction coefficients based on the merit of the situation and vary the real rate accordingly (Cf. Bernanke’s Brookings lecture, 2015). Thus, IT regimes in practice are characterised as ‘constrained discretion’, combining elements of both ‘rule’ and ‘discretion’. Central banks that adopted flexible IT regime targeting a band rather than a point inflation target as in India, have given themselves a little more operational headroom.

So what are the rules? Price stability is the principal objective, not subsumed to growth; inflation forecast to be forward-looking, incorporating inflationary expectations; transparency in communicating the rationale for variation in the real rate; and some form of accountability to win public credibility. The objective is to anchor consumers’ inflationary expectations toward the medium-term target and stabilise market expectations for the future interest rate path by minimising elements of surprise.

These elements are non-negotiable and the MPC should not be seen to be ducking these rules. However, while operating within these constraints the MPC does have discretion on finer nuances of model projections for inflation and the output gap; it can take a view on their relative weights to arrive at a consistent real rate. For example, as Mr. Bernanke revealed the US Fed had been leaning towards the output gap by assigning a higher coefficient of 1.0 against 0.5 suggested by the Taylor Rule. It is within these realms that one must judge the RBI and MPC members.

Output gap, the bone of contention

Critics argue that the ex-post real rate turned out much higher than ex-ante as actual inflation was consistently undershooting the RBI’s projections, thus hurting growth. The Economic Survey of India, Volume II, points out that these errors have persisted over 14 quarters with the margin increasing over time. But did that affect growth as captured by a widening, negative output gap?

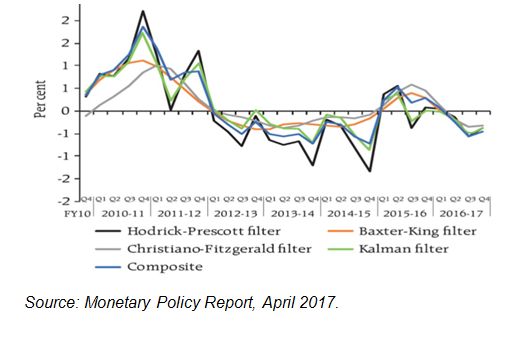

A close observation of the RBI’s output gap chart indicates a relatively large negative output gap since the first quarter of 2012-13 (FY13:Q1) that closed by FY16:Q1; in fact, some of the filters showed a small positive output gap sustaining over the next five quarters. The gap, which turned negative thereafter, reversed its direction again in FY17:Q4 and is now expected to further close as GVA (gross value added) growth is projected accelerating to 7.3% in FY18 (Figure 1). It was evident that actual output had been closer to potential output, and remained relatively stable. Thus, the unintended tightening could have positively contributed to a sharp fall in inflation without much output sacrifice. The average sacrifice ratio over FY16, FY17, and FY18 could well turn out to be closer to zero. Then why are the critics worried?

Recall at this point that India is the rare exception in terms of timing its switchover to FIT regime when both inflation and inflationary expectations were running high. The RBI was thus simply sticking to its operational rule, that is, if the estimated output gap was closer to potential the balance must tilt towards inflation, especially if inflationary expectations are to be anchored over business cycles. Where was the fault with the RBI or MPC?

We have no doubts that consistently big inflation forecast errors can increase market uncertainties, dent the framework’s credibility. But in an ex-post analysis, it appears critics are disproportionately focused upon inflation forecast errors. The heart of the dispute should instead lie in errors in estimations of potential output and the output gap. As potential output is an unobserved variable, its estimation should have been open to rigorous scrutiny. But the MPC that was instituted in October 2016 appears to have concurred with the RBI, steadily maintaining that the output gap was small and closing gradually over the next few quarters. It was only in June 2017 that Dr. Dholakia broke away from this consensus to claim the negative output gap had been persistent and expanded in recent quarters.

Figure 1. RBI’s output gap estimates

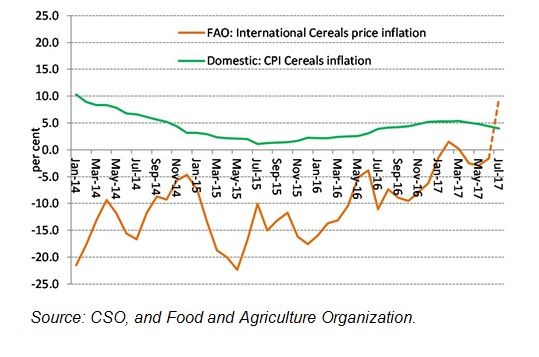

Figure 2. Cereals inflation

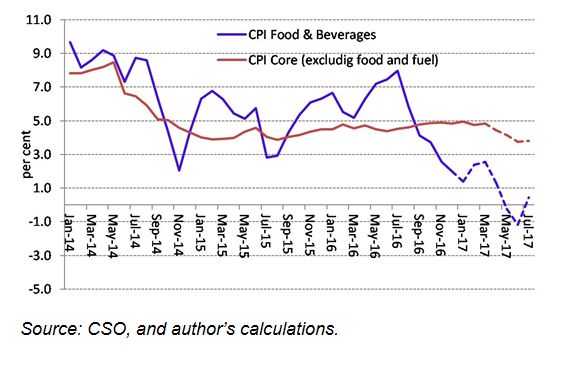

Figure 3. CPI inflation: Food & beverages vs. core

Wherein lies the truth?

To be fair to the RBI and its staff, they have been sharing their methodology and estimates with public. Like many other central banks, they use several filters to estimate potential output. These filters deploy different statistical techniques generally associated with isolating the trend in time series GDP (gross domestic product) data. The RBI transparently acknowledges impediments to these econometric estimations: limited data points, new base year from 2011-12, and no backcast series consistent with the new GDP methodology. What else could they have done?

Could the RBI have attempted an alternative production function model? Perhaps they do and share with the MPC, but there is nothing in the public domain. What we do know is that in the absence of credible unemployment statistics, such models can hardly be relied upon for high frequency policy action. Neither do we have any robust estimates of natural rate of unemployment to estimate potential output, nor high-frequency unemployment data to estimate changes in output over a business cycle. The Labour Bureau’s quarterly employment survey and the CMIE’s (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd.) large sample unemployment survey are yet to gain policy credibility.

Then how do we substantiate that the output gap is large and increasing? Dr. Dholakia invokes often cited high-frequency lead indicators such as stagnant capacity utilisation, falling manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI), slowing exports and investment demand, and weakening industrial outlook survey, to buttress his case. But these indications were not new; their misalignment with CSO’s (Central Statistics Office) new GDP data has long been a matter of intense debate. Nor does their recent trend depict any marked change to invite special attention. At best these could provide grounds for some qualitative fine-tuning, but they lack the rigour and precision to contradict results of econometric model estimates that are inbuilt into the soul of the IT framework.

Food price volatility breeds market uncertainty

The RBI may be seeking comfort from the fact that a higher real rate, though unintended, has not affected growth as output has remained close to its estimated potential. It might also be pleading helplessness for keeping the real rate high as inflationary expectations still remain high. But consistent and large errors in headline CPI inflation projections could have dented its credibility, increased market uncertainty.

A closer examination shows these errors are largely attributed to errors in projecting food inflation as core inflation has been relatively stable, slowing gradually only in recent months. But minimising these errors is easier said than done. The model must pick up seasonal upticks in food prices while accounting for a downward drift in trend attributable to supply side improvements. The model errors get pronounced and are very difficult to track when variations are caused by sharp corrections in a few items, example, vegetables or pulses! These errors appear compounded this summer because food inflation defied its seasonal uptick and plunged deep into negative territory when most models predicted some degree of mean-reversion. Problems could intensify further if the impact of demonetisation turns out more prolonged than the baseline V- or U-shaped recovery assumptions.

Is low food price inflation structural? The Economic Survey, Volume II makes the case from a standpoint of lower international oil and food prices, concluding import parity prices will likely remain stable. For the RBI to buy into this narrative would be betting against global food price and exchange rate movements! A sharp rise in international cereal prices (Figure 2) in July 2017 only underscores such risks. Durable price corrections would depend solely upon productivity-enhancing policy measures. Could the RBI isolate a single food item where government policy has led to sustained productivity gains and output stabilisation?

RBI’s admission it was unsure if inflation declines were structural or transitory further accentuates uncertainty. To worsen matters, the change in direction of inflation expectations raises doubts about its reliability. The Patel committee report was emphatic that shocks to food and fuel inflation within the CPI basket have the largest and most persistent impact on overall inflation expectations, a strong reason why it recommended targeting headline CPI and not CPI-core inflation. How does the RBI account for a counterintuitive turn in direction at a time when food inflation has been falling sharply over 10 months?

The RBI’s palpable lack of confidence was revealed in the June 2017 policy statement, where it preferred to go with a range forecast of 2-3.5% in H1 and 3.5-4.5% in H2 of FY18, rather than a point projection. What confidence would markets gain if the range is as high as 100-150 bps1? Its guidance in August appeared more ambivalent, overwhelmed by several unknowns.

The FIT framework has been in operation for more than three years coinciding with a period when international oil, food, and metal prices collapsed to multi-year lows. Yet the RBI has failed to come to terms with food price volatility and the associated unpredictability of inflation and inflationary expectations. It is time it should revisit its inflation anchor and assess if targeting CPI-core inflation could have brought more stability and credibility to the FIT regime (Figure 3).

Blame the framework, not its practitioner

If critics are upset about an inflexible MPC, then they should not blame its practitioners − Dr. Urjit Patel and his co-members − who have to work within the FIT framework’s operating principles. Instead blame Dr. Patel, the report writer who designed and prescribed the framework. If Dr. Dholakia is convinced that CPI food price inflation would converge to CPI-core inflation, then why not make a case for making CPI-core as the point inflation anchor with medium-term target at 4%? That would minimise projection errors and stabilise market expectations while removing the band altogether.

Further, if Dr. Dholakia is making a case for a large negative output gap that cannot be captured in any econometric model, would he be comfortable using WPI-core as close proxy for manufacturing sector demand constraints? I have flagged that WPI-core inflation as a proxy for producer price inflation needs to be factored in while taking a call on the real rate (Kohli 2013a, 2013b, 2014). My contention was that persistent divergence between the GDP deflator and CPI inflation could potentially lead to a suboptimal outcome because the real rate for producers remained much higher than for consumers, a key factor in slowing down investment. In fact, the IT regime’s theoretical framework strongly backs the GDP deflator as the true inflation in an economy; CPI inflation figures only as an operational proxy to condition consumers’ expectations that go into wage negotiations as also its high-frequency availability. Bringing in WPI-core inflation through a simple and transparent design structure within the IT framework could respond to producers’ concerns.

Here are my suggestions:

(i) In the base case scenario when both inflation and output gap are closer to zero and WPI-core converging with CPI-core we are in an ideal world because the GDP deflator will not significantly deviate from CPI-core. The real rate then should be primarily decided by the deviation of inflation expectations from the 4% medium-term target;

(ii) When WPI-core is projected above CPI-core, the real rate could be higher than the base-level real rate by the extent of the diversion, even going above 1.75%; and,

(iii) When WPI-core is projected lower than CPI-core, the converse should happen. That is, the real rate should go below the base-level real rate, even turning negative if the divergence becomes too large.

The above would certainly appear like an Indian version of the IT framework, but could give manufacturing the much required space to breathe and come alive.

Notes:

- A basis point (bps) is one hundredth of a percent. Basis points refer to a common unit of measure for interest rates and other percentages in finance.

Further Reading

- Hammond, G (2012), State of the art of inflation targeting – 2012, Handbook – No. 29, Centre for Central Banking Studies, Bank of England.

- Bernanke, BS (2015), ‘The Taylor Rule: A benchmark for monetary policy?’, Brookings Blog, 28 April 2015.

- Government of India (2017), Economic Survey, 2016-17, Volume II, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, New Delhi.

- Kohli, R (2013a), ‘Fighting inflation: then and now’, Financial Express, 25 October 2013.

- Kohli, R (2013b), ‘Should RBI prefer CPI over WPI?’, Financial Express, 21 November 2013.

- Kohli, R (2014), ‘Monetary policy: How much can RBI ease?’, Financial Express, 16 December 2014.

- RBI (2017), ‘Monetary Policy Report – April 2017’, 6 April 2017.

- RBI (2014), ‘Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework’, January 2014 (Chairman, Dr Urjit Patel).

- Taylor, John B (1993), “Discretion versus policy rules in practice”, Carnegie-Rochester Series on Public Policy, 39:195-214, North Holland. Available here.

- Taylor, JB (1999), Monetary Policy Rules, University of Chicago Press.

09 October, 2017

09 October, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.