India’s low female labour force participation is a complex social phenomenon, resulting from – among other things – patriarchal norms, rural-urban transitions, and a mismatch of supply and demand factors. Based on a field study undertaken in the vicinity of four north Indian cities, this article shows that mobilities, and ease of access to the home, are the most crucial determinants of women’s work participation.

This is the first of a five-part series on ‘Urbanisation, gender, and social change’.

According to International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates, India’s female labour force participation rate (FLFP) dropped from 32% in 2005 to 21% in 2019 – the lowest rate in South Asia, and among the lowest in the world. This precipitous drop in women’s engagement in the labour market has attracted the attention of academics and policymakers alike. Low FLFP in India is necessarily a complex social phenomenon, resulting from – among other things – patriarchal norms (Jayachandran 2021), rural-urban transitions (Neff et al. 2012), and a mismatch of supply and demand factors (Deshpande and Singh 2021).

Much of the literature characterises women as ‘working’ or ‘not working’, but this characterisation masks the nuances of work near or within the home, which make up the bulk of women’s work in India. In a new study (Chatterjee and Sircar 2021), we conceptualise a woman’s choice to work outside the home as a strategic decision that balances expectations at home with a possible wage outside the home. The key insight is that when demands in the home are sufficiently high – and, thus, a strategic consideration for entering the labour market – the desire to enter the labour force will necessarily entail work that is part-time and near the home, what we describe as work that has both flexibility and proximity. To be clear, these demands may not just be about time spent in the home, but also a belief that it is the ‘duty’ of the female household member to do household tasks.

To shed light on this puzzle, we analyse descriptive data and a survey experiment in the vicinity of the north Indian cities of Dhanbad (Jharkhand), Indore (Madhya Pradesh), Patna (Bihar), and Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh), teasing out the role of proximity and flexibility in women’s willingness to enter the labour force. Our core insight is that because many women state a preference for part-time work near the home, travelling greater distances for work compels women to exit the labour market.

In other words, women may indeed prefer to enter the labour force, but only on a part-time basis near the home. This means that one should not conflate the refusal to enter the labour market with a preference for not doing so. It also suggests that a characterisation of an insufficient labour market demand for women is incomplete without specifying details about the flexibility of the work schedule and the proximity to the home of any potential employment opportunities.

Agriculture and female labour force participation

While there is significant variation in the industrial composition of each of our four study locations, women are consistently far more engaged in agriculture as compared to the male primary wage earners (PWEs) in the household, with working women being 18-29 percentage points more likely to be engaged in agriculture than their male PWE counterparts. Indeed, a majority of women employed outside the home are engaged in agriculture in all of our study locations except Dhanbad, whereas a minority of male PWEs are engaged in agriculture in each study location. Given that less than 25% of working-age women are engaged in income-generating work in each of our research sites, this suggests that vast majority of women are engaged in activities within or near the home. Furthermore, women are less likely to be engaged in the labour force when agriculture is not available as a source of employment.

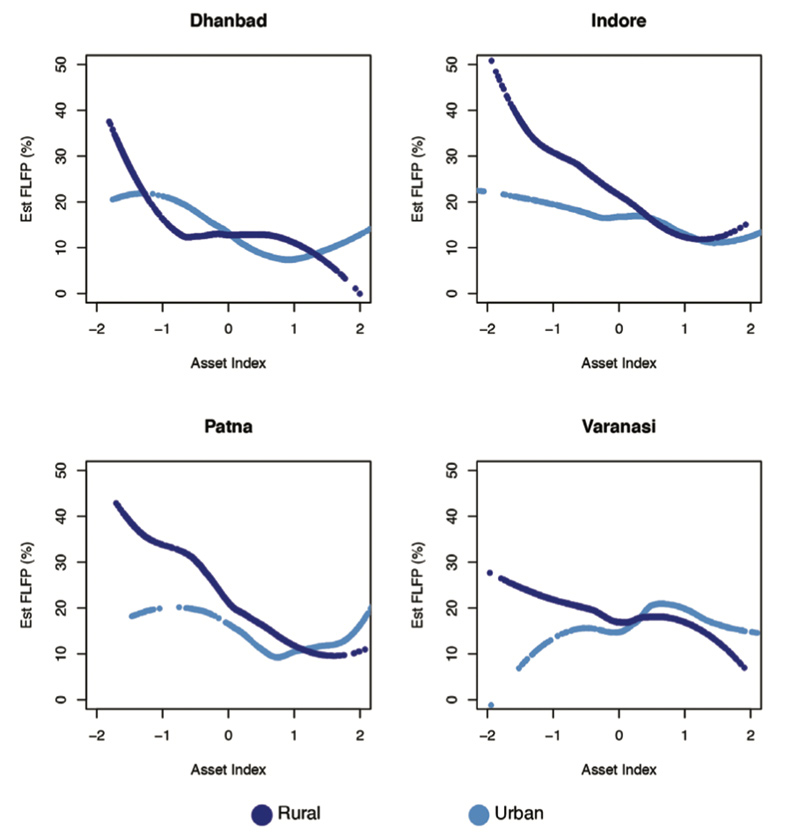

To understand the role of rural-urban transitions in structuring the labour market for women, we used official administrative classifications of urban and rural localities across our sample. We then modelled the likelihood that a woman enters the labour force as a function of a household-level asset index in each study location.

Figure 1. Rural-urban gap in female labour force participation

Figure 1 describes these trends across our four sites of study. Rural areas consistently show higher levels of FLFP for the poorest households (the one possible exception is Dhanbad, with overall low levels of agricultural work). But, at moderate levels of wealth, the FLFP rate in rural areas converges with that of urban areas. We interpret this as a result of the dearth of opportunities with sufficient wages for women beyond agricultural work, which women (or households) opt out of when incomes are higher.

Indeed, the wealthiest households in Dhanbad, Patna, and Varanasi actually display slightly higher FLFP. Perhaps women with sufficient wealth (and human capital) have greater opportunities for skilled, white-collar work in urban contexts – even if the overall levels remain quite low.

Notably, the rural-urban employment gap in FLFP is about more than just the differences in wealth between rural and urban households. We suggest that this difference is due to the fact that women in rural households may often engage in agricultural jobs that are both flexible and proximate. By contrast, in non-agricultural spaces, the availability of jobs meeting the conditions of proximity and flexibility is significantly lower.

Preferences for flexibility and proximity

In each city, we randomly selected a working-age female to serve as a respondent in addition to the PWE. In total, we were able to survey both the PWE and a working-age female in 12,579 households, with a sample size between 2,854 (Indore) and 3,447 (Varanasi) in each city. If the (female) respondent was unemployed, we asked her whether she would be willing to do a ‘suitable job’ and what kind of contract she would prefer for her job. In sum, we surveyed 9,777 unemployed women across the four cities, with a sample size between 2,295 (Patna) and 2,674 (Dhanbad) in each city. Table 1 shows that the vast majority of women would like to work, and among them, a significantly higher percentage prefer part-time work, which is consistent with the preference for flexibility in labour contracts.

Table 1. Women’s preferences for a flexible work schedule

|

Work Preferences |

Dhanbad (%) |

Indore (%) |

Patna (%) |

Varanasi (%) |

|

Stated a willingness to work |

58 |

52 |

60 |

66 |

|

Regular full-time work |

41 |

28 |

38 |

33 |

|

Regular part-time work |

59 |

65 |

57 |

62 |

|

Occasional/causal work |

0 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

In order to interpret the preference for a flexible work schedule, we asked for reasons to explain their work schedule preferences. We allowed a large number of answers. Here we segregate these into two types of answers: (a) Those based on earnings and quality of fit, which is consistent purely with individual preferences or financial needs; and (b) Those based on need to attend to household concerns and proximity, consistent with our model of trade-offs. Respondents were allowed to give multiple reasons.

In Table 2, we display the percentage of respondents giving each response and segregate the six responses into these two categories. We viewed the respondent as giving reasons around concerns of household work if she answered that her reason for a job preference was that: (a) She could take care of things at home; (b) The job was available nearby; or (c) The family approves of the job. We viewed the respondent as giving financial or individual reasons if she answered that her reason for a job preference was that: (a) It contributed financially to the household; (b) It had decent pay; or (c) She is qualified for the job.

Table 2. Women’s reasons for labour market preferences

|

Reasons for preferred work schedule |

Dhanbad (%) |

Indore (%) |

Patna (%) |

Varanasi (%) |

|

|

Distance or household work constraints |

Can take care of things at home with this job |

33 |

14 |

23 |

21 |

|

This job is available nearby |

5 |

16 |

11 |

14 |

|

|

Family supports and approves of this job |

6 |

7 |

10 |

14 |

|

|

Financial need or individual preferences |

Contribute financially to household income |

21 |

11 |

23 |

19 |

|

Decent pay |

11 |

9 |

6 |

2 |

|

|

Qualified for this job |

7 |

8 |

7 |

12 |

|

Across all of our study sites, the top reason given was that the respondent would be able to take care of things at home. In general, the set of concerns consistent with our model – household work constraints were reported more often than those of individual preferences or financial needs — and proximity was explicitly given as a top answer in three of four study sites.

A survey experiment to understand preferences

A number of complex factors likely impact preferences to enter the labour market. Here, we abstract away from the type of job contract at play to understand the relative impact of multiple factors on the willingness to enter the labour market, through a novel survey experiment. We manipulate three factors – household income, assistance from others in household duties, and distance to possible work – to understand how they affect a woman’s willingness to do a ‘suitable job,’ where the set of suitable jobs were provided earlier in the survey by the respondent.

We manipulated three prompts simultaneously in a survey experiment, against a base case of the respondent being offered a job in her mohalla (neighbourhood). In order to do so, we randomly assigned respondents eight versions of vignette in the survey (see Table 3). The base case is represented in version 1, in which we asked the respondent (a working-age unemployed female) if she would be willing to do a suitable job if it were offered in the neighbourhood. In every other version of the vignette, we asked about the respondent’s willingness to do a suitable job when prompting that: 1) The PWE had to leave work; and/or 2) A family member came to help; and/or 3) The job is being offered one hour away.

Table 3. Survey experiment structure

|

Versions |

Primary wage earner |

Help |

Physical proximity to job opportunity |

|

1 |

- |

- |

In the neighbourhood |

|

2 |

- |

- |

One hour away |

|

3 |

- |

Someone comes to help |

In the neighbourhood |

|

4 |

- |

Someone comes to help |

One hour away |

|

5 |

Has to leave work for some reason |

- |

In the neighbourhood |

|

6 |

Has to leave work for some reason |

- |

One hour away |

|

7 |

Has to leave work for some reason |

Someone comes to help |

In the neighbourhood |

|

8 |

Has to leave work for some reason |

Someone comes to help |

One hour away |

The regression results in Table 4 describe the relative impact of each manipulation (income, assistance, distance) on a woman’s willingness to enter the labour market. The magnitude of the impact of travelling one hour to work on the willingness to do a suitable job is by far the largest effect we observe, with distance causing a 12 to 23 percentage point drop in the willingness to enter the labour force across our four sites of study. Somewhat surprisingly, income seems to matter little in the stated preference for entering the labour market. Assistance, too, matters little in willingness to enter the labour market – suggesting the work at home for women is more consistent with expectations and duty, and not just time spent in the home.

Table 4. Survey experiment regression results

|

Dhanbad |

Indore |

Patna |

Varanasi |

|

|

Distance |

-0.233*** (0.018) |

-0.146*** (0.02) |

-0.163*** (0.02) |

-0.123*** (0.02) |

|

Help |

-0.031 (0.018) |

0.003 (0.02) |

0.022 (0.02) |

-0.077*** (0.2) |

|

Income |

-0.047*** (0.018) |

0.01 (0.02) |

-0.024 (0.02) |

-0.012 (0.02) |

|

Constant |

0.478*** (0.018) |

0.455*** (0.02) |

0.49*** (0.02) |

0.520*** (0.021) |

|

N |

2,674 |

2,344 |

2,295 |

2,464 |

Notes: (i) p-value is the probability of getting results at least as extreme as the results observed, given the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. A p-value lower than a mentioned significance level would be considered statistically significant (if p < 0.01, it is statistically significant at the 1% level). * p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001 (two-sided). (ii) The coefficients should be interpreted as the proportion change in people willing to enter the labour force for a “suitable job.”

These survey experiment results strongly affirm the role of mobility and distance in structuring labour force outcomes.

Conclusion and policy implications

Previous studies have shown how rising incomes and human capital intersect with rural-urban transformations to cause declines in FLFP (Afridi et al. 2018, Neff et al. 2012). But there is much less work explicating how rural-urban transformations affect spatial and economic structures that adversely affect women’s entry into the labour force.

As our discussion shows, even after accounting for wealth, rural areas display higher levels of FLFP than urban areas. With social constraints in tow, we show that women espouse preferences for part-time work near the home – conditions that characterise the agricultural labour market, but not the urban labour market. As India urbanises, labour market opportunities fitting those criteria are in shorter supply, causing women to leave or become unwilling to enter the labour market.

Our survey results confirm these intuitions: women are 12 to 23 percentage points less likely to express a preference to take up a suitable job if they have to travel at least one hour to work. The magnitude of these effects is far greater than the impact of the primary wage earner (PWE) of the household losing their job, or other family members assisting the woman in household duties. Our findings suggest mobilities, and ease of access to the home, as the most crucial determinants of FLFP – even more than economic factors commonly assumed to have the largest impact on entry into the labour market.

We emphasise that, while this is not a study on labour market demand, these results suggest that because the urban labour market provides an insufficient number of jobs for women with the characteristics of proximity and flexibility, greater urbanisation will naturally lead to lower FLFP due to expectations of (unpaid) work in the home. We also underscore the pitfalls of deducing labour market demand for women from employer preferences or sectoral demand, without detailed knowledge about the type of work contract or the proximity of the job.

Our study has significant implications for policy design. While one may hope for transformative changes in economic structure which dramatically boosts wages for women, this does not seem to be on the horizon for India. One prudent road for policy design seems to be investing in safe, efficient, and proximate transport for women in urban spaces to reduce travel times, as well as promoting industries that allow for more flexible work schedules. Invariably, the process of increasing FLFP will be a long and arduous task. Urban design that maximises women’s mobility will be a key component of this process.

The next part in this series will discuss working women’s agency in India.

I4I is on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Further Reading

- Afridi, Farzana, Taryn Dinkelman and Kanika Mahajan (2017), “Why are fewer married women joining the work force in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades”, Journal of Population Economics, 31:783-818. Available here.

- Deshpande, A and J Singh (2021), ‘Dropping Out, Being Pushed Out or Can’t Get in? Decoding Declining Labour Force Participation of Indian Women’, IZA Discussion Paper No. 14639.

- Jayachandran, Seema (2021), “Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries”, International Monetary Fund Economic Review, 69(3): 576-595. Available here.

- Neff, D, K Sen and V Kling (2012), ‘The Puzzling Decline in Rural Women's Labor Force Participation in India: A Reexamination’, GIGA Working Paper No. 196. Available here.

06 December, 2021

06 December, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.