Castes in India are closely associated with certain occupations and determine the jobs done by millions. This study uses a new dataset to show that a large proportion of workers still work in their caste's traditional occupation. Looking at counterfactuals, it finds that removing occupational ties and castes' hierarchical order reduces the share of workers in traditional occupations. However removing the links between caste, intergenerational learning, and social networks causes productivity losses and a substantial decrease in economic output.

Workers’ social identity affects their occupation choices, and therefore the structure and prosperity of the aggregate economy. In the Indian caste system, work and identity are particularly intertwined. Each Indian caste is usually associated with a single traditional occupation, which was historically seen as the proper vocation for members of that caste – their ‘dharma’. There is also a social hierarchy of castes creating discrimination, notably during education and participation in the labour force, both therefore directly affecting the Indian economy.

Today, these ancient caste traditions still determine the job choices of millions of Indian workers. In a recent study (Cassan et al. 2021), we develop and estimate a structural model to quantify the effects of castes’ occupational ties and social hierarchy on workers’ income, and the aggregate productivity and output of the Indian economy.

Overrepresentation of castes in their traditional occupation

In counterfactuals, we remove castes’ hierarchical and occupational ties and find that the share of workers employed in their traditional occupation decreases substantially. However, the effects on aggregate output and productivity are relatively small, because gains from a more efficient allocation of human capital across occupations are offset by productivity losses from weaker caste-occupation networks and reduced learning across generations.

We construct a new dataset that combines information on individuals’ caste, occupation, and wages with historical evidence of castes’ traditional occupations and social hierarchy. Our analysis is at the sub-caste (or jati) level, which defines workers’ identity and social networks. We use the term caste for simplicity.

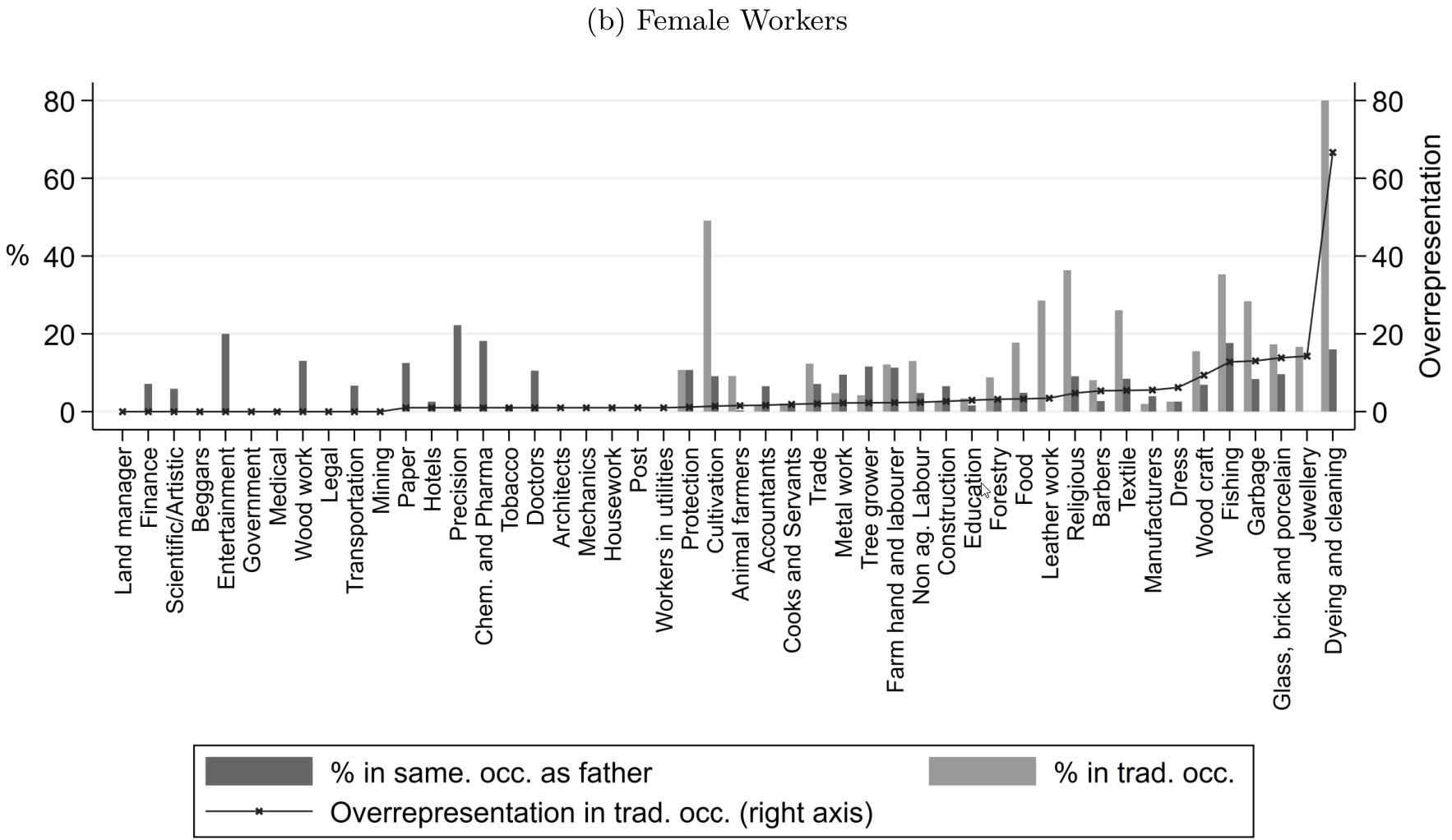

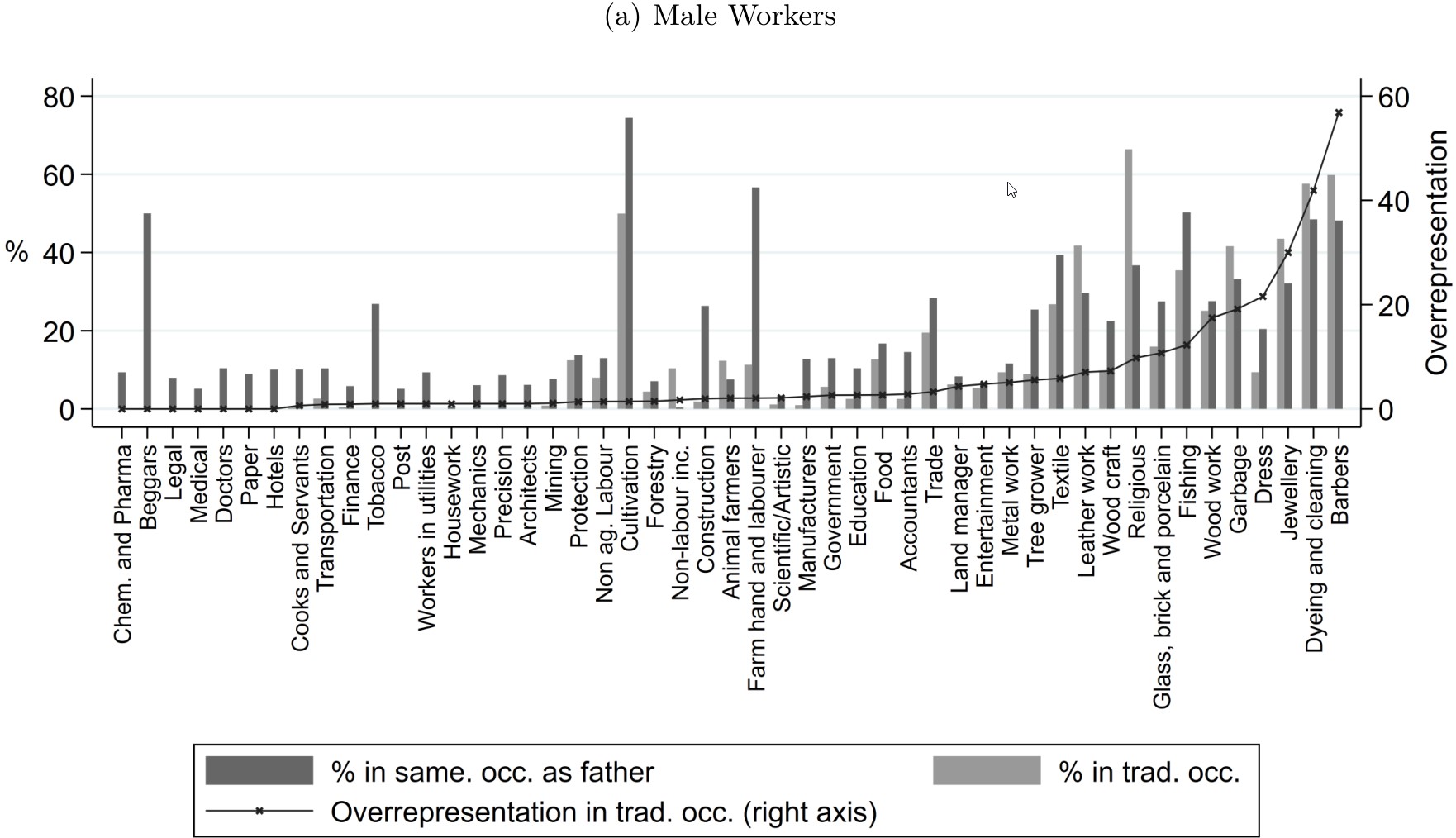

We find that castes are still greatly overrepresented in their traditional occupations in modern India. The light grey bars in Figure 1 show the share of workers in each occupation who work in their caste’s traditional occupation. There is large heterogeneity across occupations – some occupations (such as barbers or clothes washing) are predominantly done by traditional workers, while other occupations (such as advocates or hotel operators) have close to no traditional workers.

Figure 1. Share of male (upper panel) and female workers (lower panel) following their traditional or father’s occupation

This finding illustrates an important point: Traditional occupations were defined in pre-industrial times, when many ‘modern’ occupations did not yet exist or represented only a small part of the economy. Over the course of technological change and structural transformation, these modern occupations became more important and are now the most productive and highest-return occupations in the economy.

Keeping workers in their caste’s traditional occupations can therefore lower productivity in two ways: first, individuals cannot freely choose the occupation in which they are most productive (that is, they do not select into occupations based on their comparative advantage). Second, high ability individuals continue working in their low-return traditional occupations (such as agriculture, laundering, and pottery) when, in the absence of the caste-occupation affinity, they might apply their skills more productively in high-return occupations (such as teaching, engineering, and law).

However, the sorting of workers into their caste’s traditional occupations can also have positive effects on productivity by coordinating castes into strong caste-occupation networks, and by enabling knowledge transfers across generations. These two channels can create ‘path dependence’ beyond workers’ own preferences: even if workers no longer feel attached to their traditional occupations, they might work in them to take advantage of strong caste networks and intergenerational learning. The dark grey bars in Figure 1 show that the share of workers who work in the same occupation as their father, is correlated with the occupation’s share of traditional workers.

Quantifying the aggregate effects of castes’ occupational links

To quantify the effects of castes’ ties to their traditional occupations, we develop and estimate a structural general equilibrium Roy model of educational and occupational choice1 that incorporates caste identity through several channels: a direct preference for traditional occupations; social hierarchy implying different costs for education by caste; wage and occupation-level discrimination; productivity effects from working in one’s father’s occupation; and network effects at the caste-occupation level. We consider the economy in general equilibrium where wages in each occupation adjust as workers reallocate across occupations.

Workers differ in occupation-specific productivity and general ability. In the absence of distortions, workers select occupations based on their comparative advantage, and high-ability workers are drawn toward ‘modern’ occupations where returns to ability are high. Additionally, workers’ schooling choices depend on education costs and the returns that they expect to receive in their future occupation. Those who expect to enter their traditional low-return occupation therefore have low incentives to become educated.

The caste system is a hierarchical structure, with certain groups seen as ritually superior and others as ‘polluting’. To avoid conflating the role of identity and discrimination, we estimate occupational ties to traditional occupations, wage discrimination, and education costs separately for workers from hierarchically lower castes, and for women. We allow wage discrimination against low castes to be higher in occupations traditionally linked to higher castes. We also allow the attachment to traditional occupation to vary depending on the social ranking, as occupations traditionally linked to lower castes can be unpleasant or servile. Higher castes may have a specific disinclination to work in occupations linked to lower-ranked castes (which are seen as ‘ritually polluting’), so we allow castes’ utility of working in an occupation to vary based on the social distance between the occupation and their caste.

We estimate the model and perform counterfactuals which quantify the importance of castes’ occupational links and castes’ hierarchy for the economy’s occupational structure, productivity, and output.

Direct and indirect effects of castes’ occupational preference

In our counterfactuals, we analyse how the Indian economy would differ if we removed castes’ ties to their traditional occupations, castes’ hierarchical order, or both. In each set of counterfactuals, we evaluate i) the direct effects of castes’ occupational ties, discrimination, and hierarchy and ii) the indirect effects through intergenerational learning and caste networks.

To study the direct effects, we keep the distribution of fathers’ occupations and caste-occupational networks fixed. We find that removing ties to traditional occupation has very minor direct effects: market output increases by 0.2% with fixed education, and by 0.3% with endogenous education. Effects are small because the basic structure of the economy remains relatively unchanged. The allocation of human capital improves as workers opt out of their traditional occupations; however, many traditional workers simply get replaced by other (similar) workers, which keeps the occupational structure and aggregate output similar.

Removing castes’ hierarchical order has larger direct effects, with output gains of 0.3% with fixed education and 3.5% with endogenous education. Schooling increases by 12% because we eliminate caste differences in education costs, and because expected returns to schooling increase due to the removal of wage discrimination in higher-ranked occupations.

We then additionally remove castes’ occupational ties through parental learning by eliminating the correlation between fathers’ occupations and traditional occupations. Aggregate output now declines by 7% when removing castes’ ties to their traditional occupations, with a smaller decline of 2.8% when removing caste hierarchy. Aggregate effects are negative because workers must choose between benefitting either from strong caste networks (in their traditional occupation) or from intergenerational learning (in their father’s occupation).

Removing castes’ ties to their traditional occupation while adjusting caste-occupation networks endogenously leads to an even larger decline of 10% in aggregate output. Despite these negative aggregate effects, workers improve their selection into occupations based on their individual characteristics: high-ability workers sort more toward high-return occupations, education increases, and the aggregate share of traditional workers decreases. The structure of the economy changes more as a result, with human capital contracting in typical traditional occupations, but expanding in modern occupations.

However, gains from the improved human capital allocation are smaller than losses from reduced intergenerational learning and weaker caste networks. This finding emphasises the importance of caste identity in organising castes into strong occupation networks that enable productivity spillovers. Once we eliminate this coordination element, occupational networks are less clustered at the caste level, which lowers network effects and can therefore lower aggregate productivity and output.

Removing castes’ occupational ties has the strongest negative effect on workers with low human capital because it does not induce them to move into high-skill occupations, while they continue to suffer from weaker caste networks and reduced intergenerational learning. Workers at the middle of the human capital distribution gain the most, because they increase their education and shift toward occupations that better align with their individual talent and ability.

The dynamic costs of persistence of occupational identities

Our analysis suggests a possible explanation for the remarkable persistence of castes’ occupational identities in India despite deep changes in the country’s economic structure. If the static economic costs are mild, but individuals receive substantial utility from conforming with social norms, then these norms tend to persist over long periods of time. Our findings suggest that the main costs of identity frictions may be dynamic and occur over the course of structural transformation.

Note:

- The Roy model is a framework for analysing comparative advantage. The original model analysed occupational choice with heterogeneous skill levels.

Further Reading

- Cassan, G, D Keniston and T Kleineberg (2021), ‘A Division of Laborers: Identity and Efficiency in India’, NBER Working Paper 28462.

18 November, 2022

18 November, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.