Early childhood development programmes have become increasingly common in developing countries. This article analyses historical administrative data from the roll-out of India’s Integrated Child Development Services programme and finds significant long-term positive health, education, and labour-market impacts for adults who were exposed to the programme as children. However, siblings of children with greater programme exposure have worse outcomes as parents reallocated investments away from them.

The question of how to build human capital with limited resources remains a key policy problem in developing countries. Several developing countries have responded with direct provision of health and education services for young children. As early childhood development programmes become increasingly common in developing countries, it is important to understand how parents respond to such programmes. Do parents reallocate their investments over time to invest earlier or later in children? Do parents reallocate their investments across children to reinforce programme exposure or compensate for lack of exposure to such programmes? These questions are important for two reasons. First, they enable us to understand the mechanisms behind the large impacts that we see from early childhood programmes (Currie and Vogl 2013, Almond and Currie 2011). Second, studying sibling spillovers helps us to understand who benefits and who is harmed from such programmes.

In a recent paper (Ravindran 2018), I study these questions using historical administrative data (1975-2016) from the roll-out of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme in India, the world’s largest early childhood development programme. The ICDS programme is an integrated health and pre-school education programme for children with an age eligibility criterion stipulating that services be provided to pregnant mothers and children under six years of age. Exploiting variation over time and across India, I use a research design that compares children born in different districts within the same year and state, while also controlling for a number of individual characteristics.

First, I show that the ICDS programme had significant positive long-run health, education, and labour-market impacts for adults who were exposed to the programme as young children. Second, I consider a number of parental investments in children for nutrition and educational expenses and show that parents reinforce exposure to the government programme in two ways: (i) parents front-load their investments to earlier ages of their child, and (ii) parents invest more in children exposed to the programme, at the expense of siblings who are not exposed. This addresses a gap in the literature where less attention has been paid to how parents respond to such programmes. I show both theoretically and empirically that reallocation of parental investments depends on (i) the interaction between investments by the government and parents, (ii) parental preferences over inequality in their children’s human capital, and (iii) the technology for human capital formation, which maps parental and government investments over time into human capital. I also consider parental responses in the form of labour-supply decisions and show that there were no programme impacts on parents’ employment and wages in my setting.

Positive and persistent programme impacts

The first contribution of my paper is to study the long-run impacts of the world’s largest early childhood development programme. The introduction of the ICDS in 1975 provides an excellent setting where individuals exposed to the programme when young are in their thirties, and even forties, today. The challenge, however, is in determining how much exposure to the programme these individuals had. For this purpose, I worked with India’s Ministry of Women and Child Development to collect historical administrative data on the ICDS programme that details when and where each ICDS centre was built. Linking this rich data on more than a million centres across India with a large number of household survey datasets enables me to study the long-run impacts of the programme. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study to present the long-run impacts of the world’s largest early childhood development programme.

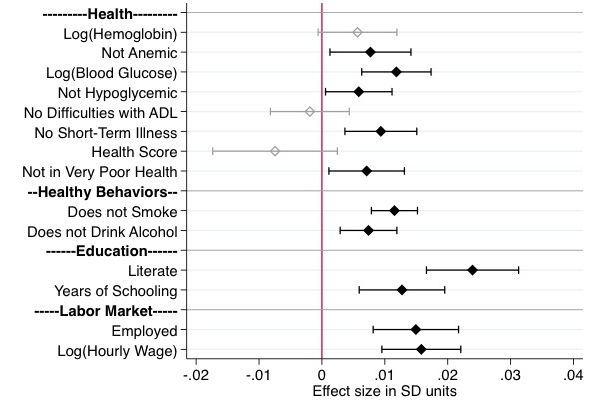

Figure 1. Long-term impacts of Integrated Child Development Services

Notes: (i) ADL refers to Activities of Daily Living, including the ability to speak, hear, and walk normally. (ii) SD refers to standard deviation1.

Notes: (i) ADL refers to Activities of Daily Living, including the ability to speak, hear, and walk normally. (ii) SD refers to standard deviation1. Figure 1 summarises the long-term impacts of the programme, where programme intensity is defined as the number of ICDS centres per 1,000 children. Each line is a 95% confidence interval2 corresponding to the relevant point estimate3. The programme impacts are measured in standard deviation units and should be interpreted as intent-to-treat (ITT) impacts4. I find positive and persistent programme impacts for adults on a number of health, education, and labour-market outcomes. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for India and India Human Development Survey (IHDS) provide a number of objective and subjective measures of health from bloodwork and survey questions. I consistently find positive impacts of the programme on these measures of health and healthy behaviours. Furthermore, individuals exposed to the programme when young are also significantly more likely to be literate, have more years of schooling, be employed, and earn a higher wage. These impacts stem from greater programme exposure during the eligible age range to obtain services from the ICDS programme.

Reallocation of parental investments across children

The second contribution of my research is to study how parents respond to early childhood programmes in developing countries. I develop a theoretical model that delivers several predictions that I can test for with my data. The theory builds on the following intuition: government programmes that are complementary to parental investments raise the benefits from investing in children. Parents respond by increasing investments in children exposed to an increase in programme intensity. However, this may ‘crowd out’ investments in siblings of children exposed to an increase in programme intensity. Using my data, I then show that parents front-load their investments in children exposed to the programme, while also reallocating investments towards children with programme exposure, at the expense of their siblings. Consequently, siblings of children with greater programme exposure have worse health and education outcomes.

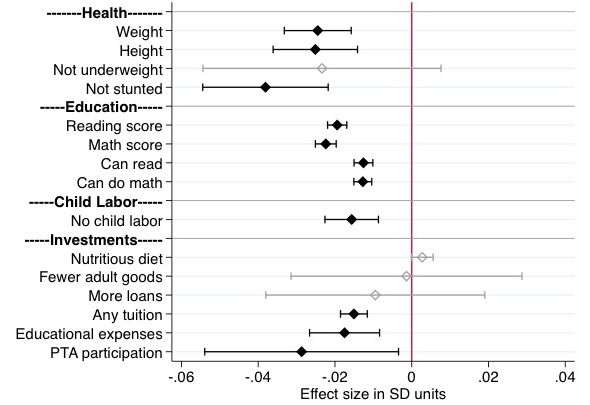

Figure 2. Impacts of increase in average programme exposure of siblings on a child’s outcomes

The opening of every ICDS centre generates substantial variation in programme exposure between siblings of different ages. I use this variation to summarise the impacts of an increase in the average programme intensity of siblings on a child’s outcomes in Figure 2. The sign of each variable is such that values to the left of zero indicate worse outcomes or lower investments by parents. In addition to the datasets mentioned earlier, I use ASER (Annual Status of Education Report) data for test scores of children and the National Sample Surveys (NSS) for employment outcomes of children and parents. I find consistently negative impacts from having siblings exposed to greater programme intensity, across a number of health, education, and labour outcomes. This is driven by a corresponding reduction in investments by parents. Furthermore, I find that these crowd-out effects are larger for girls.

Implications of results

How large are the sibling spillovers in relation to the direct impacts of the programme for exposed individuals? To answer this question, I conduct a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of the programme. The benefits from the programme arise due to the direct wage impacts and health impacts that I monetise using the reduction in lost days of work. Taking into account these direct benefits yields an internal rate of return (IRR) of 9%5. Taking into account both the direct and indirect impacts, however, yields an IRR of 8%, a 10% decrease. These findings highlight that the overall impacts of early childhood programmes depend on both the direct impacts on exposed cohorts, as well as the indirect impacts that arise due to the reallocation of parental investments. Taken together, the results help us understand the mechanisms behind the positive impacts of early childhood development programmes and the negative spillovers of such policies.

Notes:

- Standard deviation is a measure that is used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values from the mean value (average) of that set.

- A confidence interval is a range computed from observed data that likely contains the true value of an unknown population parameter. Most commonly, the 95% confidence level is used; this means that the fraction of calculated confidence intervals that contain the true population parameter tends toward 95%.

- A single value given as an estimate of a parameter of a population is called point estimate.

- An intent-to-treat analysis presents results for all individuals exposed to the programme, and does not focus exclusively on the impact of the programme for individuals who choose to take it up.

- The internal rate of return is a measure of profitability that is used to compare projects in terms of the rate of return, or the rate at which the benefits exceed the costs.

Further Reading

- Almond, Douglas and Janet Currie (2011), “Human Capital Development before Age Five”, Handbook of Labor Economics, 4b (15).

- Currie, Janet and Tom Vogl (2013), “Early-Life Health and Adult Circumstance in Developing Countries”, Annual Review of Economics, 5: 1-36.

- Ravindran, S (2018), ‘Parental Investments and Early Childhood Development: Short and Long Run Evidence from India’, Job Market Paper, 28 December 2018.

11 March, 2019

11 March, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.