In the twelfth post of I4I’s month-long campaign to mark International Women’s Day 2023, Bhalotra et al. show that mortality during and after childbirth remains high, even where the knowledge and resources to avoid this are available, and demonstrate that raising the share of women in parliament can trigger action. Leveraging the introduction of gender quotas across developing countries, they identify reductions in maternal mortality. Investigating mechanisms, they find that gender quotas are associated with increased skilled birth attendance and prenatal care utilisation, a decline in fertility and an increase in female schooling.

The chance that a 15-year-old girl will die within 42 days of giving birth is 1 in 190 worldwide, and 1 in 45 in low-income countries (World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). Maternal mortality is only the tip of an iceberg, the mass of which is maternal morbidity (Koblinsky et al. 2012). There is no single cause of death and disability for men aged 15-44 that is close in magnitude to maternal mortality. Reducing maternal mortality is of both intrinsic and functional value, as it favourably influences women’s human capital attainment, employment, and overall economic growth (Jayachandran and Lleras-Muney 2009, Albanesi and Olivetti, 2016).

Women in policymaking and maternal outcomes

The causes of maternal mortality are well understood, and skilled care before, during and after childbirth can prevent about three-fourths of maternal deaths (WHO, 2019). Rather than obstetricians and gynaecologists, this requires relatively low-cost primary care and midwifery at delivery. We put forward the hypothesis that male-dominated parliaments have not sufficiently prioritised the reduction of maternal mortality, and propose increasing women’s involvement in policymaking – this can make a difference since women leaders may be innately more concerned about the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) because they identify with the risks (Bhalotra and Clots 2014), and/or because they may have clearer information on the risks faced by women (Powley 2007, Ashraf et al. 2020).

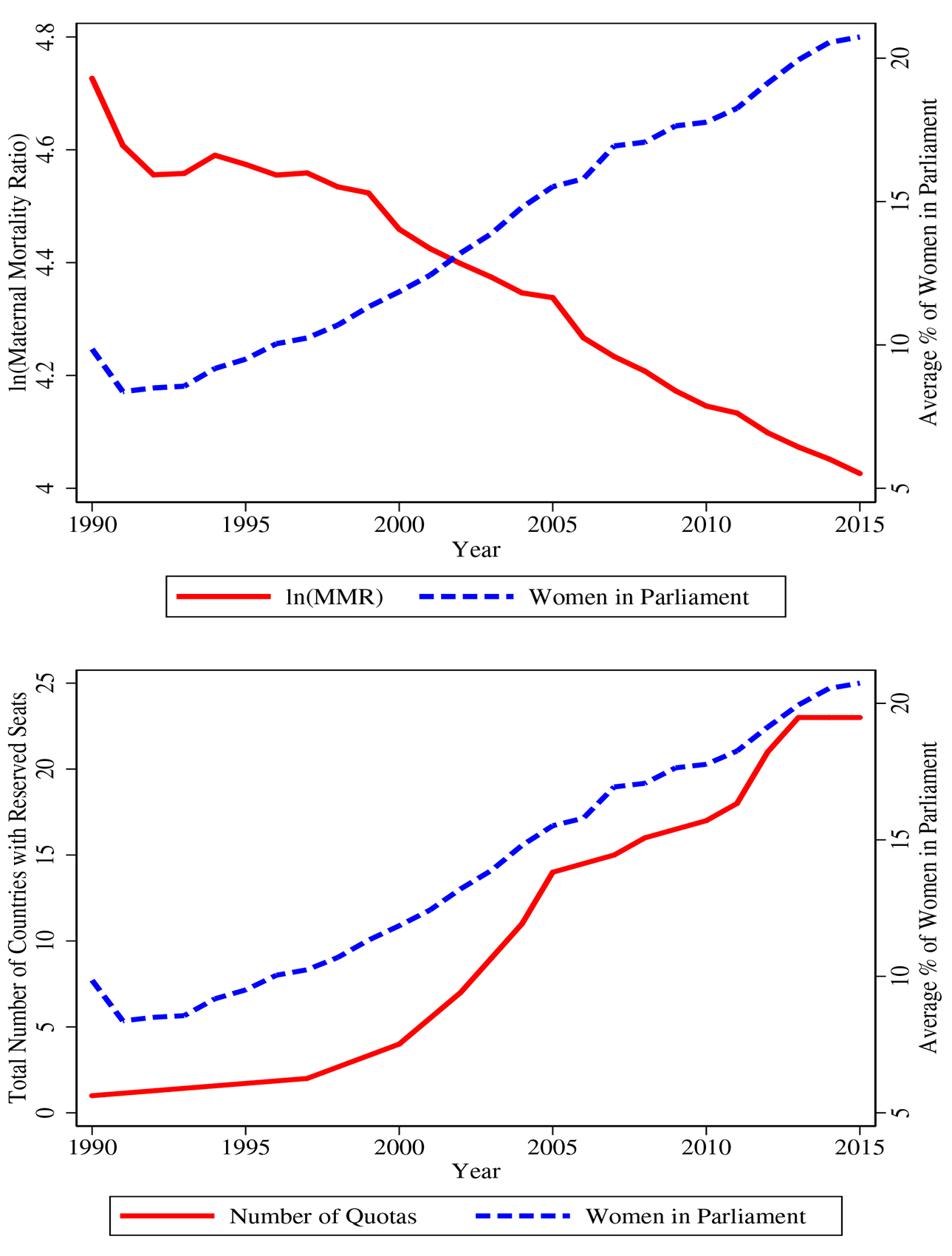

The broad trends are consistent with our hypothesis. MMR has shown an unprecedented fall of 44% since 1990, a period in which the share of women in parliament has risen unusually rapidly, from under 10% in 1990 to more than 20% in 2015 (Figure 1, left panel). In a recent study (Bhalotra et al. 2023) we investigate if these trends are causally related. This is potentially challenging because the share of women in parliament has evolved smoothly, making it hard to disentangle its impact from other slowly evolving trends. We leverage the abrupt legislation of reserved seat quotas for women in parliament. A wave of quota adoption swept through developing countries, with 22 reforming during 1990-2015, the period we analyse. The right panel of Figure 1 shows this strong trend, also showing that the share of women in parliament has tracked quota implementation.

Figure 1. Trends for women in parliament, gender quotas and MMR

Notes: i) The figures show raw trends in number of countries with parliamentary gender quotas, the percentage of women in parliamentary seats, and the log of the maternal mortality ratio. ii) The sample contains 178 countries for which we have annual data through 1990-2015.

Delineating the effects of gender quota legislation on maternal mortality

In this research, we employ a difference-in-difference event study. This involves testing for a sharp break in the trajectory of the outcome (maternal mortality) after the implementation of gender quota, relative to outcomes before the quota, within the treated country and relative to other countries that had not yet implemented quotas.

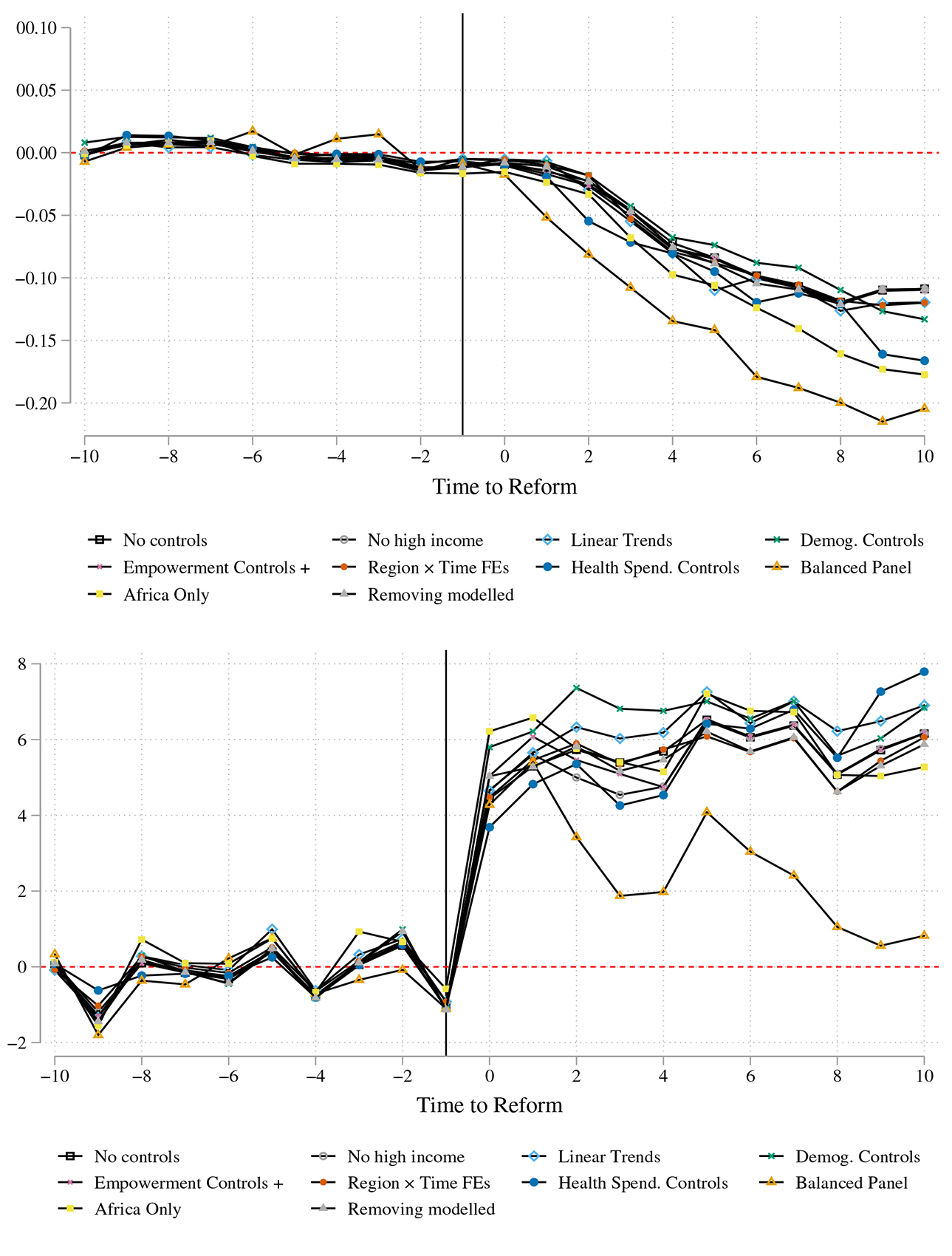

We demonstrate discontinuous changes in the trend of women’s representation following quota legislation, and show that this was mirrored by a sharp drop in maternal mortality of 8-12%. Gender quota impacts on MMR are persistent, increasing in the pre-intervention level of MMR, and in the share of seats reserved. Figure 2 documents these patterns, also showing that they are robust to varying the sample and to varying the controls in the estimating equation (further details included in Bhalotra et al. (2023)). The figure shows that quota implementation is followed by a jump in the share of women in parliament and a sharp drop in maternal mortality.

Figure 2. Trends in log of MMR (left panel) and share of women in parliament (right panel)

Notes: i) Event study style difference-in-difference estimates are obtained following Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille (2020). ii) The vertical line represents when quotas for women were implemented in parliament. Although quotas were implemented at different dates in different countries, we recalibrate dates in event time, setting the date of reform as -1

How robust are these results?

The identifying assumption is that, in the absence of quota legislation, outcomes in the treated countries would have evolved smoothly and in the same manner as outcomes in the untreated countries.

The timing of quota adoption is not idiosyncratic, but instead correlated with the outcome (that is, maternal mortality) on account of a common factor – trends in gender progressivity. We show that our results are not driven by democratisation, nor by other drivers of quota adoption identified in political science literature (Krook 2010). There remains the threat that underlying trends in gender progressivity may have both triggered quota legislation and led to lower MMR, without quotas having any causal impact on MMR. This would be in line with broader evidence that the timing of legislation is not random, but that legislation is passed when social preferences have evolved to support it (Doepke and Zilibotti 2005, Platteau and Wahhaj 2014). However, we find no evidence that quota adoption is preceded by an uptick in any of 18 indicators of women’s economic rights, civil liberties and property rights– our estimates are not sensitive to this suite of indicators. Since these tests are ultimately limited to tests on observables, we also examine robustness of our estimates by using a range of alternative techniques and relaxing the identifying assumption (see Bhalotra et al. (2023) for more detail).

To confirm that implementation of gender quotas was not dependent on other factors, we also repeat the analysis using the variation in the implementation of village-level gender quotas across Indian states. This is a setting in which previous work has shown that state-level adoption of the village-level quota was quasi-random (Iyer et al. 2012). We identify a significant relationship of similar magnitude across India, which also broadly affirms our findings.

Implications for policy depend on whether quota adoption directly impacts MMR, or whether it acts through inducing changes in the composition of women giving birth – for example whether they were older or younger, or more or less educated.1 We find no evidence that compositional effects drive our findings.

We conclude that, while the progression of gender equality is likely to eventually culminate in increased attention to women’s reproductive health, this is likely to be a slow process. In contrast, quotas that give women instrumental power to action improvements can produce sharp changes. We demonstrate this mechanism, showing that quota adoption generates sharp increases in the coverage of reproductive health services, the key determinant of MMR highlighted in scientific research and promoted by WHO guidelines (Grépin and Klugman 2013, Kruk et al. 2016).

Mechanisms through which gender quotas led to declining MMR

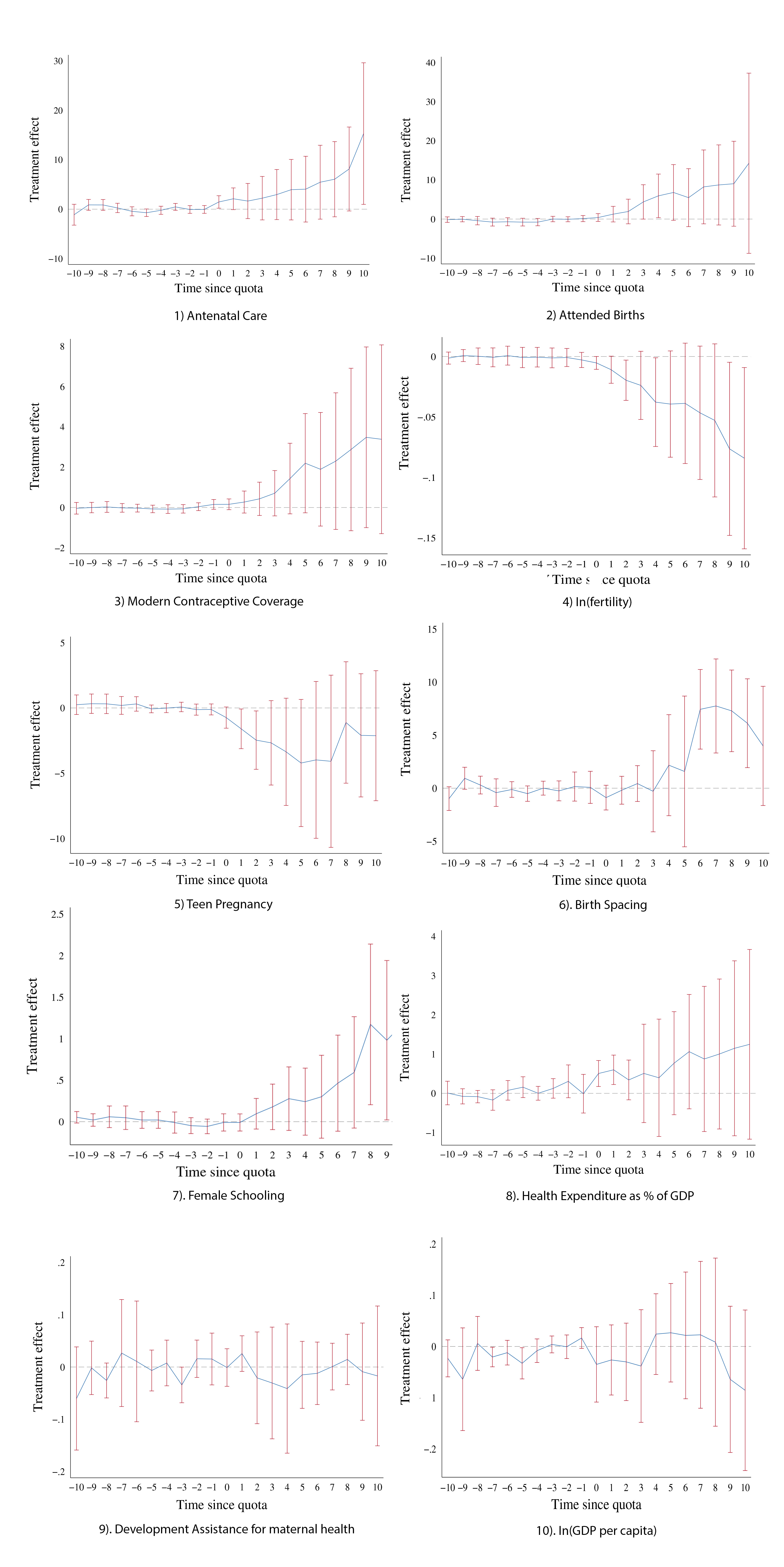

We identify increases in coverage of skilled birth attendance of 5 to 8 percentage points (that is, 6-9.6%); coverage of antenatal care of 4 to 8 percentage points (4.8-9.6%); and an increase in contraceptive coverage of 1.7% during this period. However, we find no impact of increased parliamentary representation of women on adoption of abortion legislation– which is relevant because unsafe abortion is a major cause of MMR (Girum and Wasie 2017, Clarke and Mühlrad 2021). This is possibly because there are religious barriers to abortion law, which women leaders may not be able to surmount.

We also look at whether an increased presence of women in parliament modified the demand-side determinants of MMR, including women’s rights, female education and fertility (Bhalotra and Clarke 2013, Girum and Wasie, 2017). We find no discernible impacts of quotas on women’s rights, but we identify an increase of 0.5 years in the education of young women, and a decline in the total fertility rate of 6-7%, consistent with the observed expansion of contraceptive coverage and women’s schooling. In addition to a mechanical effect given by MMR being defined as maternal death risk per birth, it will also have a scale effect, tending to reduce the number of maternal deaths at any level of risk per birth through improved maternal health outcomes. We estimate that the scale effect leads to an additional decline in the maternal death count that is roughly 64% of the impact of the implementation of quotas on maternal deaths per birth.2

In view of broader concerns about reducing MMR in low-resource settings, a natural question is whether these results rely upon women parliamentarians raising resources to help women at risk. We find no evidence that more resources became available – there is no impact of gender quotas on GDP or international development assistance for maternal health (DAH). We find some evidence of increased spending on health, but this is sensitive to specification. We therefore tested whether the improvement in MMR is achieved at the cost of other health outcomes, and found no evidence that gender quotas arrest declines in male reproductive age mortality, mortality from tuberculosis (which is gender-neutral), or infant mortality – thus, there is no evidence of substitution of health priorities.

We argue that large changes in outcomes are feasible without a large increase in resources because of the low costs of relevant interventions (Dupas 2011, Banke-Thomas et al. 2020), and the slack generated by inefficiency and corruption that a motivated leader can exploit (Folbre 2012, Brollo and Troiano 2016, Baskaran et al. 2018) – we refer to evidence consistent with leaders being able to move the outcomes they prioritise by building consensus, provoking legislation, and improving policy design and delivery, including better targeting and greater outreach.

Figure 3. Changes in nine indicators after implementation of quotas for women in Parliament

Note: These nine indicators are event study style difference in difference estimates examining potential mechanisms for reduction in MMR after quotas are implemented in Parliament. For a complete discussion of definitions and sources of the variables and results for schooling gains based on gender, please refer to Bhalotra et al. (2023).

Conclusions and policy implications

Current international strategies to address MMR are focussed upon extending reproductive health coverage, but there is no recognition among policy makers of the political economy constraints on achieving this. We draw attention to the potential to achieve large improvements through raising women’s role in policy making.

Despite a wave of gender quota implementation, 130 countries in the world have none. There is thus substantial room for manoeuvre. While significant progress has been made (especially since 2000) preventable maternal mortality remains high. Our findings have implications for the recently launched Global Health 2035 report, and the ambitious Sustainable Development Goals – our findings show that targeting maternal mortality reduction (SDG 3.1) is highly complementary to targeting an increase in women’s political representation (SDG 5.5).

Our study is not only relevant to developing countries. Maternal mortality in the United States has been on the rise in recent years. Moreover, there are large black-white differentials in maternal mortality in the US that appear rooted in structural racism. The results in our paper are consistent with the view that raising the political representation of women and, in particular, black women, could redress inequalities and arrest the trend in the United States. Further research confirming this is merited.

Notes:

- To conduct tests for compositional effects we need individual data. We constructed a pseudo panel from the full reproductive histories of women available in harmonised microdata, including 10.83 million births of 3.07 million individual women surveyed in 34 different years, in 82 countries, 14 of which implemented quotas.

- Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that more than 8,000 maternal deaths worldwide were averted per year due to quotas lowering maternal deaths per birth, and an additional 5,669 maternal deaths a year were averted on account of the impact of quotas on the number of births.

Further Reading

- Bhalotra, Sonia, Damian Clarke, Joseph Gomes and Atheendar Venkataramani (2023), “Maternal Mortality and Women’s Political Participation”, Journal of the European Economic Association.

- Albanesi, Stefania and Claudia Olivetti (2016), “Gender Roles and Medical Progress.”, Journal of Political Economy, 124(3), 650–695.

- Ashraf, Nava, EricaMField, Alessandra Voena, and Roberta Ziparo (2020), ‘Maternal Mortality Risk and Spousal Differences in the Demand for Children’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, Working Paper 28220.

- Banke-Thomas, Aduragbemi, Ibukun-Oluwa Omolade Abejirinde, Francis Ifeanyi Ayomoh, Oluwasola Banke-Thomas, Ejemai Amaize Eboreime, and Charles Anawo Ameh (2020), “The cost of maternal health services in low income and middle-income countries from a providers perspective: a systematic review.”, BMJ Global Health, 5(6):e002371. Available here.

- Baskaran, Thushyanthan, Sonia Bhalotra, Brian Min, and Yogesh Uppal (2018), ‘Women legislators and economic performance’, Journal of Economic Growth, forthcoming. Available here.

- Bhalotra, Sonia and Damian Clarke (2013), “Educational Attainment and Maternal Mortality”, Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2013/4 2014/ED/EFA/MRT/PI/14, UNESCO.

- Bhalotra, Sonia and Irma Clots-Figueras (2014), “Health and the political agency of women”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(2): 164-197. Available here.

- Brollo, Fernanda and Ugo Troiano (2016), “What happens when a woman wins an election? Evidence from close races in Brazil”, Journal of Development Economics, 122(C): 28-45.

- De Chaisemartin, Clément and Xavier D’Haultfoeuille (2020), “Two-Way Fixed Effects Estimators with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects”, American Economic Review, 110(9) : 2964–96. Available here.

- Doepke, Matthias and Fabrizio Zilibotti (2005), “The Macroeconomics of Child Labor Regulation”, American Economic Review, 95(5): 1492–1524. Available here.

- Dupas, Pascaline (2011), “Do Teenagers Respond to HIV Risk Information? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya.”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1): 1-34. Available here.

- Folbre, Nancy (2012), “Should Women Care Less? Intrinsic Motivation and Gender Inequality”, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50(4): 597-619.

- Girum, Tadele and Abebaw Wasie (2017). “Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries.”, Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology, 3(1): 1-6.

- Grépin, Karen A and Jeni Klugman (2013). “Maternal health: a missed opportunity for development”, The Lancet, 381(9879): 1691-1693.

- Iyer, Lakshmi, Anandi Mani, Prachi Mishra, and Petia Topalova (2012), “The Power of Political Voice: Women’s Political Representation and Crime in India.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(4): 165-93.

- Jayachandran, Seema and Adriana Lleras-Muney (2009), “Life Expectancy and Human Capital Investments: Evidence from Maternal Mortality Declines”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1): 349-397.

- Koblinsky, Marge, Mahbub Elahi Chowdhury, Allisyn Moran, and Carine Ronsmans (2012), “Maternal morbidity and disability and their consequences: neglected agenda in maternal health”, Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 30(2): 124.

- Krook, Mona Lena (2010), Quotas for Women in Politics: Gender and Candidate Selection Reform Worldwide, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Kruk, Margaret E, Stephanie Kujawski, Cheryl A Moyer, Richard M Adanu, Kaosar Afsana, Jessica Cohen, Amanda Glassman, Alain Labrique, K Srinath Reddy, and Gavin Yamey (2016), “Next generation maternal health: external shocks and health system innovations”, The Lancet, 388(10057): 2296-2306.

- Platteau, Jean-Philippe and Zaki Wahhaj (2014), ‘Strategic Interactions Between Modern Law and Custom’ In Victor A. Ginsburgh and David Throsby (ed.), Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, Vol. 2, chap. 22, pp. 633-678. Elsevier.

- Powley, Elizabeth (2007), “Rwanda: The impact of women legislators on policy outcomes affecting children and families”, Background Paper, State of the World’s Children.

- WHO (2019), ‘Fact Sheet: Maternal Mortality’, World Health Organization

29 March, 2023

29 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.