Women’s political participation has emerged as a key element of the discourse around the upcoming state elections in India. In this post, Nalini Gulati and Ella Spencer explore the evidence on various aspects of women’s political engagement in the country – representation in government, women as political leaders, and women as active citizens.

According to the WEF Global Gender Gap Report 2020, India ranks 18th in terms of political empowerment, far better than its rank in the other dimensions of the index: 149th in economic participation and opportunity, 112th in educational attainment, 150th in health and survival, and 108th in the overall index. The political empowerment ranking sits above the UK’s ranking of 20th and significantly above the US rank of 68th.

The sub-index for political empowerment measures the gap between women and men at the highest level of political decision-making through the ratio of women to men in ministerial positions, the ratio of women to men in parliamentary positions, and the ratio of female to male heads of state in the past 50 years. India’s positioning is strongly driven by the tenure of Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister from 1966 to 1977 and then again from 1980 until her assassination in 1984. While Gandhi’s role as a prominent female leader should not be overlooked, it does somewhat skew our interpretation of India’s positioning in the index. The other two measures that constitute the index see India ranked 69th with 30% of women in ministerial positions, and 122nd with 17% of women in parliament. The sub-index also fails to factor in state-level leadership, where significant powers sits. Of India’s 28 states, currently only West Bengal has a female Chief Minister.

Besides, the political empowerment sub-index focusses entirely on leadership. In this post, we explore the evidence around a range of areas linked to women’s political participation in India, including political representation at different levels of India’s political system, women as political leaders, and women as active citizens.

Women’s political representation in India

In 1992, the 73rd Constitutional Amendment mandated that one-third of village government head positions in the country should be reserved for women. The policy was introduced to increase the political representation of women at the local level. A significant body of research has since been carried out to consider the impact of the policy, demonstrating a sharp increase in the number of women elected as village sarpanch (Duflo 2005). Further, an empirical study by O’Connell (2020) shows that the mandate accounts for a substantial portion of the increase in female candidates who contested seats in state and national legislatures since the mid-1990s.

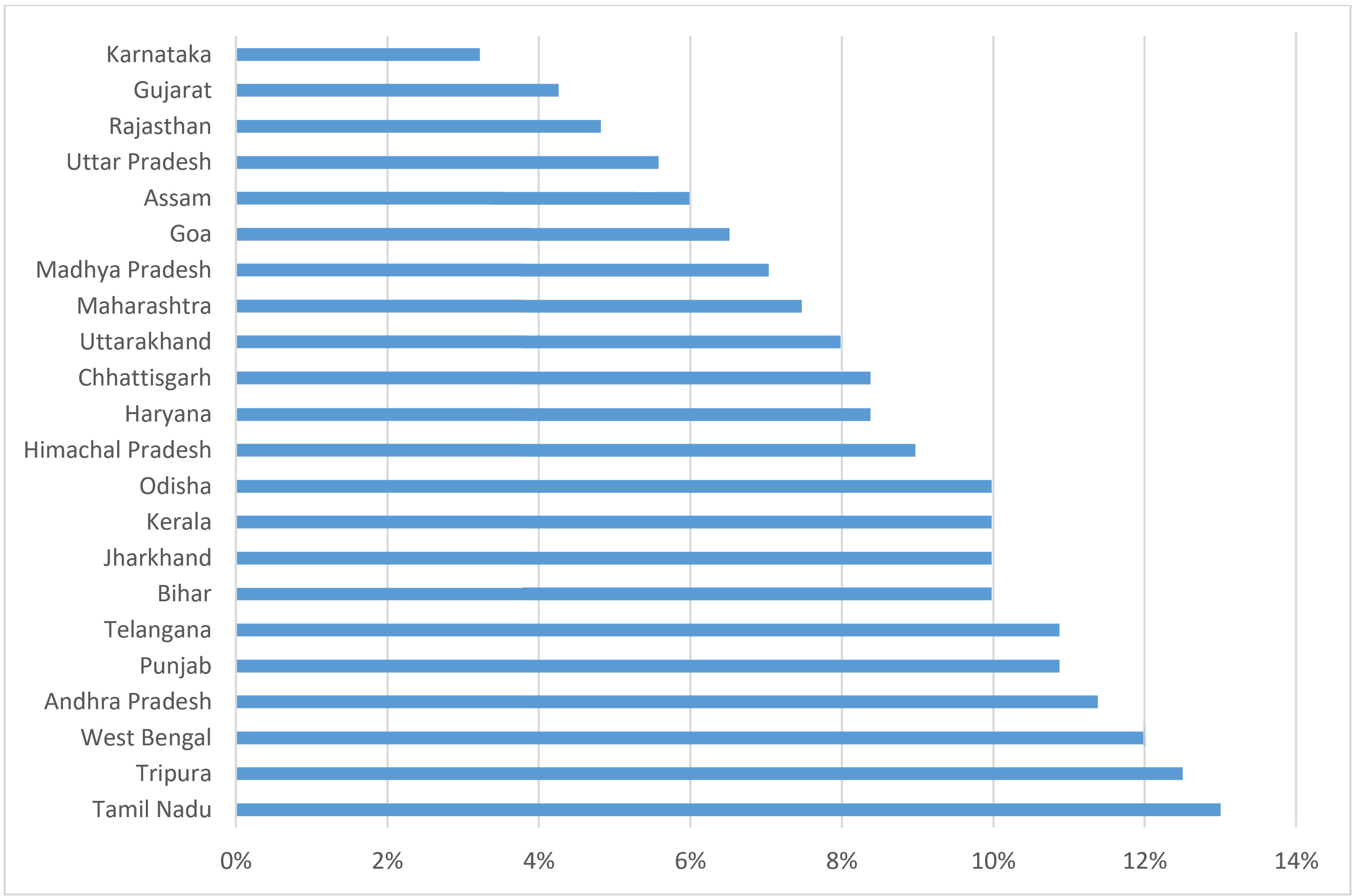

However, female representation in higher offices remains low. In particular, the representation of women at the state level has lagged significantly behind, excluding women from important seats of institutional power and decision-making. The IGC has collected data on the composition of state government leadership from their websites, as of 30 March 2021. Six states in India have no female ministers, including Nagaland, Sikkim, and Manipur. No state comes close to a third of female ministers – the highest proportion of female ministers is in Tamil Nadu with 13%, and 68% of states have less than 10% female representation in state leadership roles. Figure 1 below depicts the low rates of female representation in ministerial positions in Indian states.

Figure 1. Proportion of female ministers in state governments

The Women’s Reservation Bill, which seeks to amend the Constitution of India and reserve a third of all seats in the Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament) and in all state legislative assemblies for women, was passed by the Rajya Sabha (the upper house of parliament) in 2010. However, the Lok Sabha (lower house) is yet to put the bill to a vote for it to become a law. The bill has risen to prominence again in recent public discourse, recognising the need for increased female political representation at all levels of government.

Women as political leaders

Anecdotally there is a view that female political representatives in local government are merely a front for their male relatives. If this were so, we should see no difference in the policy choices made by political leaders based on their gender – as these would be controlled by men even in the case of female leaders holding reserved seats. However, this has been refuted by the well-known study by Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004). Using data that the researchers collected on 265 village councils in West Bengal and Rajasthan, it is seen that the reservation of a council seat has a bearing on the provision of public goods, with female leaders investing more in public goods valued by women (for example, drinking water).

Other studies point towards the effectiveness of female political leaders – but experience is key. A survey conducted in Maharashtra in 2008 (Sathe et al. 2013) find that the availability of basic public services is better in female-headed villages, when the female head has been in the job for 3-3.5 years. While an IGC study by Afridi et al. (2017) find that women leaders with no prior experience initially under-perform, they rapidly learn and fully catch up with male leaders in unreserved seats. Hence, there is a need for capacity-building and institutional support to enhance the effectiveness of policies pertaining to affirmative action and women’s participation in politics.

Given the association of female political leaders with redistributive policies, one may think that they are less effective in promoting economic growth, at least in the short to medium term. In an IGC study, Bhalotra et al. (2018), provide evidence to the contrary. Examining data for 4,265 assembly constituencies in India for the period 1992-2012, they find that women legislators raise economic performance in their constituencies by about 1.8 percentage points per year more than male legislators. The researchers attribute this striking result to female leaders being less corrupt, more efficient, and more motivated than their male counterparts.

Whether females in power are actually less corrupt is, however, an open question. Based on an artefactual field experiment in rural Bihar, Gangadharan, Jain, Maitra and Vecci (2015) demonstrate that in villages that have previously experienced a female village chief, women show a greater tendency to appropriate resources when acting as a leader, vis-à-vis men. A possible explanation put forth by the authors is that female leaders expect to be treated poorly, leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy where they behave in a negative manner. Alternatively, in an environment with few opportunities for leadership, women act myopically and take one-off decisions when presented with an opportunity as they do not expect to be re-elected.

Nevertheless, the presence of women political leaders is found to have other positive social outcomes. Analysing data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Iyer and Mani (2012) note a large increase of 26% in the documented crimes against women, after the increased political participation of women as a consequence of the 1993 amendment. Digging deeper, the researchers find that this is driven not by a surge in the actual crimes committed against women, but by the increased reporting of such crimes. There is an increase in the responsiveness of the police under women political representatives, which encourages women to voice their concerns.

While it is commonly believed that female political leaders can serve as role models for girls and women in society, the mechanism does not seem to work for political candidacy. Analysing constituency-level data covering all state elections in India during 1980-2007, Bhalotra, Clots-Figueras, and Iyer (2018) find that there is a decline in the entry of new women candidates following a woman’s electoral victory. This decline is most pronounced in states with entrenched gender bias and in male-headed political parties, which is in line with male backlash against women performing non-traditional roles (see, for instance, Gangadharan et al. 2014).

Women as active citizens

The sex ratio of voters in India (number of women voters to every 1,000 male voters) has displayed an impressive increase from 715 in the 1960s to 883 in the 2000s, with the 2019 general election being the first time when women were more likely to vote as compared to men. Yet, women are less likely to participate in politically oriented public activities such as election campaigns or protests, or to identify with a political party.

A survey in Uttar Pradesh (Iyer and Mani 2018) corroborates that the biggest gender gaps are indeed in non-electoral participation (for example, attending village meetings) rather than in electoral participation. The gender gaps are partially explained by factors such as women having significantly lower knowledge about political institutions and electoral rules; lagging behind men on self-assessed leadership skills; and needing permission to go outside. Exploring ways to enhance women’s presence in the political space, an experiment in Madhya Pradesh (Prillaman 2018) shows that women who participated in a self-help group (SHG)1 were twice as likely to attend village assembly meetings or make a claim on local leaders. It is suggested that the positive effect is largely the result of women’s coordinated action to jointly demand representation and combat backlash from men.

Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004) – in the study mentioned above – show that women are more likely to participate in the policymaking process if the leader of their village council is a woman. When the Pradhan is a woman, the percentage of women among participants in the Gram Samsad2 is significantly higher (increasing from 6.9% to 9.9%). Women in these villages are also twice as likely to have addressed a request or complaint to the Pradhan in the last six months. The researchers note this as being consistent with the idea that political communication is influenced by citizens and leaders belonging to the same gender. They also put forth the possibility that this increased participation of female villagers in the policymaking process may play a role in the policy decisions of female Pradhans.

While there is still a long way to go for women’s political representation in India, especially at higher levels of government, with more female political leaders and more women exercising their democratic rights, we can hope for policy change that may contribute towards India’s improved performance on the other indicators of women’s economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, and health and survival.

Published in collaboration with the IGC Blog.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- SHGs are informal associations of 10 to 20 women from the same village that act as informal savings and credit institutions.

- A body consisting of people registered in the electoral rolls within the area of the panchayat at the village level is called gram sansad. In many states, it is known as gram sabha.

Further Reading

- Afridi, Farzana, Vegard Iversen and MR Sharan (2017), “Women Political Leaders, Corruption, and Learning: Evidence from a Large Public Program in India”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 66(1).

- Artiz Prillaman, S (2019), ‘The persistent gender gap in political participation in India’, Ideas for India, 15 April.

- Baskaran, T, S Bhalotra, B Min and Y Uppal (2018), ‘Women legislators and economic performance’, IGC Working Paper.

- Bhalotra, Sonia, Irma Clots-Figueras and Lakshmi Iyer (2018), “Pathbreakers? Women’s electoral success and future political participation”, The Economic Journal, 128(613): 1844-1878.

- Biniwale, M, S Klasen, J Priebe and D Sathe (2016), ‘Can the Female Sarpanch Deliver? Evidence from Maharashtra’, Ideas for India, 23 October.

- Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra and Esther Duflo (2004), “Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India”, Econometrica, 72(5): 1409-1443. Available here.

- Duflo, Esther (2005), “Why Political Reservations”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2-3): 668-678.

- Gangadharan, L, T Jain, P Maitra and J Vecci (2015), ‘Women leaders and deceptive behaviour’, Ideas for India, 29 January.

- Gangadharan, L, T Jain, P Maitra and J Vecci (2014), ´Social Norms and Governance: The Behavioral Response to Female Leadership´, Monash University and ISB.

- Iyer, L and A Mani (2013), ‘The power of women’s political voice’, Ideas for India, 17 June.

- O'Connell, Stephen D (2020), "Can Quotas Increase the Supply of Candidates for Higher-Level Positions? Evidence from Local Government in India", The Review of Economics and Statistics, 102(1): 65-78.

31 March, 2021

31 March, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.