Youth unemployment remains a significant challenge in India, with large-scale public skilling programmes achieving limited success in improving labour-market outcomes. This article explains the approach adopted by Generation India Foundation, which emphasises the selection of candidates with foundational skills and interest in particular job roles, providing high-quality and relevant instruction, and proactively seeking out job placements. It finds that this approach leads to greater employment and earnings compared to business-as-usual programmes.

India is experiencing a demographic “youth bulge”, creating a large young worker pool with the potential to drive economic growth and improve living standards. However, in order to leverage this opportunity, millions of young people will need to find productive employment. This remains an ongoing challenge – in 2022, the youth unemployment rate in India was about 18%, compared to 5% for the labour force as a whole (International Labour Organization, 2024).

Recognising the role of vocational training in inclusive economic growth, in 2015, the Government of India established an umbrella initiative, Skill India, to coordinate and streamline skill development programmes and initiatives across the country. Despite their large scale, many government efforts have struggled to deliver strong employment outcomes. For example, the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) scheme, the government’s flagship vocational training and skill certification scheme, trained almost 14 million candidates between 2015 and 2023, but only about 18% of these were placed into jobs (Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, 2023).

Globally, although there are examples of positive impacts of vocational training programmes on employment and earnings, the results of many programmes have been disappointing (McKenzie 2017). The success of any given programme likely depends on factors such as social, economic, and labour market conditions; characteristics and existing skill levels of targeted groups; and characteristics of training programmes such as quality, alignment of skills with labour market demand, and support for job placement.

Generation India Foundation’s approach to vocational training

To help address the skills gap, Generation India Foundation (part of the global non-profit skilling organisation Generation) offers short bootcamp-style vocational training programmes for Indian youth, which are tailored to high-demand occupations in skilled trades, healthcare, technology, and customer services and sales. Since launching in 2015, Generation India has expanded its programmes to serve more than 55,000 trainees across the country. These programmes combine technical and soft skills training with job placement support and mentorship. Key features of Generation’s approach include:

- Trainee and instructor selection: The screening process for trainees includes assessments, aptitude tests in basic English and numeracy, and interviews to identify candidates with a genuine interest in the relevant job role and the underlying motivation and skills to succeed. Instructors are screened for relevant industry experience, an aptitude for teaching, effective engagement with trainees, and a willingness for self-improvement.

- Curricula and instruction: Curricula development follows an activity mapping approach that identifies key skills needed to succeed in a role by engaging with real employees and employers. Curricula emphasise practical versus theoretical sessions, integration of material related to behaviours, mindsets, and soft skills with technical material, and preparation of candidates for job interviews.

- Support for job placements: Generation encourages strong job placement outcomes by launching trainee cohorts with written (though non-binding) placement commitments from employers for at least 50% more trainees than are in the cohort to provide a buffer in case some job opportunities do not materialise. It then works with training providers to support placements, with a substantial share of payments to the contracted training providers tied to job placement and retention rates. Each trainee cohort is also assigned a mentor, who supports trainees during training and for about three months thereafter.

In a recent study (Borkum, Cheban and Felix 2023), we examine the labour market outcomes of trainees from two Generation India training programmes implemented under Project AMBER (Accelerated Mission for Better Employment and Retention), a collaboration with the government and the World Bank. Project AMBER has trained nearly 24,000 youth and with continued World Bank Support, Generation India is scaling its impact to 100,000 youth nationwide. We benchmark these results against learner outcomes from equivalent public training programmes offered through the business-as-usual public system.

Data and methodology

We focus on Generation India’s Retail Sales Associate (RSA) and Customer Care Executive (CCE) programmes, which are primarily offered in Tier-2 or Tier-3 cities. The former prepares trainees for entry-level customer sales associate roles in the brick-and-mortar retail industry, and typically lasts between 6-12 weeks; the cohorts included in the study were trained in-person in 10 cities across India. The latter prepares trainees for entry-level customer service call centre operator roles, and typically lasts between 5-17 weeks, with study cohorts trained using a mix of online and in-person instruction in 12 cities across India.

We use data from a phone survey with a representative sample of learners to compare the long-term outcomes of Generation learners with those from equivalent publicly funded programmes that used the standard, non-Generation methodology. The sample size includes 560 learners from 47 training cohorts for Generation programmes, and 509 learners in 115 training cohorts for comparison programmes. The phone survey with these learners was conducted between 12 and 18 months after training completion (15 months on average).

To ensure a fair comparison, we carefully match comparison programme cohorts by training centre type, Indian state in which they were trained, and timing of the Generation programme cohorts. We also use regression analysis to account for sampling stratum (the division of the sample into sub-groups based on shared characteristics) and statistically control for the effects of the few observed differences in trainee socio-demographic characteristics (sex, level, and age) between Generation and the comparison group on employment outcomes.

Findings

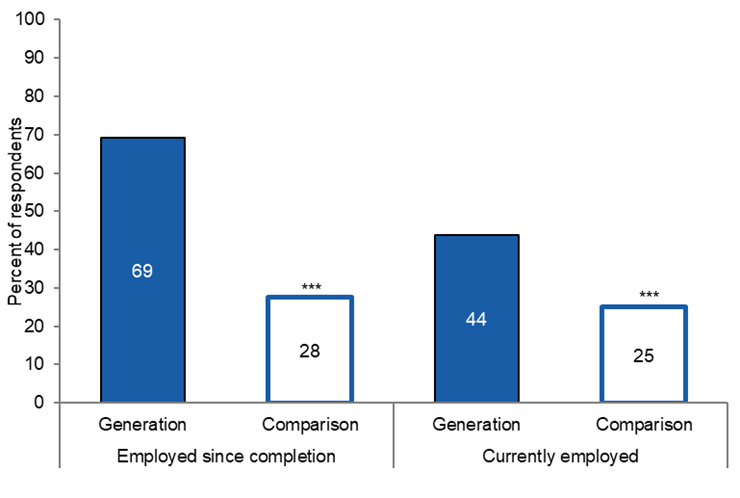

Overall, 69% of Generation learners held a job at some point in the survey period, compared with 28% of comparison learners in non-Generation programmes. Employment rates on the survey date, which might be more indicative of learners’ long-term prospects for stable employment, were 44% for Generation learners compared with 25% for comparison learners (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Employment outcomes among vocational trainees

Notes: (i) Sample sizes for employed since completion are 457 for Generation learners and 509 for comparison learners. Sample sizes for currently employed are 459 for Generation learners and 508 for comparison learners. (ii) *** indicates the statistically significant difference between Generation and comparison learners at the 1% level.

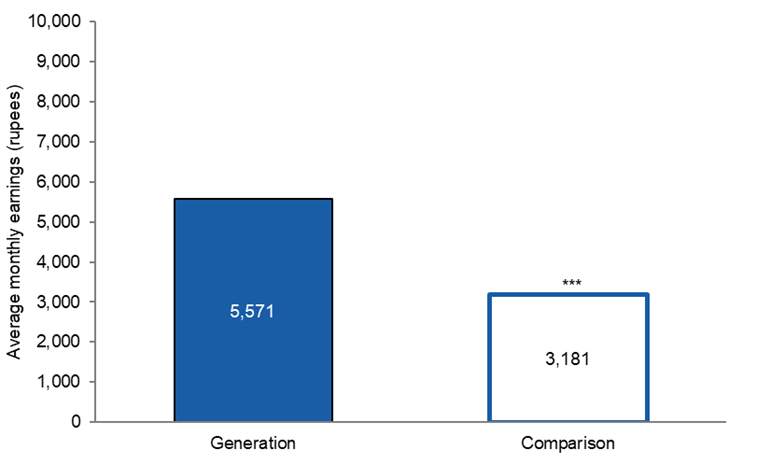

Among employed Generation learners, average monthly wages in their current or most recent job were Rs. 11,818 (US$ 143), comparable to the comparison learners. However, factoring in unemployed individuals (who have zero earnings) among the full sample, Generation learners were earning about 75% more on average than comparison learners at the survey date (Figure 2). This is a key measure of how Generation training might be associated with improved welfare.

Figure 2. Average monthly earnings at the survey date for the full sample

Notes: (i) Earnings are zero for those not employed at the survey date. (ii) Based on the distribution of wages in the survey data, we top-code a handful of outlier wages at the 95th percentile of non-zero earnings, replacing their wage with a threshold value. (iii) Sample sizes are 456 for Generation learners and 506 for comparison learners. (iv) *** indicates the statistically significant difference between Generation and comparison learners at the 1% level.

Almost all employed Generation learners held full-time jobs – about one-third hold a permanent job contract, and about 7 in 10 were satisfied with their job. About one-half of Generation learners report that their current or most recent jobs were very or somewhat relevant to their training, 18 percentage points higher than the proportion for comparison learners. This is consistent with Generation selecting trainees with a genuine interest in and commitment to the job role and its intensive efforts to find trainees relevant jobs upon programme completion.

Policy implications

Our study finds that Generation’s methodology – which emphasises seeking highly motivated and committed trainees, providing high-quality instruction, and proactively seeking out job placements – is associated with stronger labour market outcomes compared to the business-as-usual public sector training approaches in India.

Although Generation’s approach is more expensive, a simple analysis suggests that it is likely to be cost effective. Calculations based on the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship’s common norms for skill development schemes suggest that the cost per trainee for the broad category of business-as-usual programmes (including RSA and CCE) was about Rs. 17,600 (US$ 214) in 2022. In comparison, Generation India’s estimated cost per trainee was about Rs. 21,000 (US$ 255) in 2022. Combining these cost data with our findings for employment rates and average trainee earnings suggests that the costs per percentage point of long-term employment achieved and per rupee of average trainee earnings generated are both about 30% lower for Generation programmes than business-as-usual programmes.

As India faces consistently high youth unemployment rates, Generation’s success offers a scalable model for future initiatives to improve employment opportunities and economic prospects for the country’s youth. Although Generation’s careful selection of trainees with the innate interest, aptitude, and motivation to succeed in their chosen programmes implies that not all unemployed youth can be served using this approach, this selection is an important step towards improving the efficiency of the public vocational training system in the context of limited resources. Complementary interventions such as improved career guidance for youth or programmes to improve youth mindsets could play an important role in steering youth towards suitable vocations offered through Generation-style training.

Further Reading

- Borkum, E, I Cheban and E Felix (2023), 'Generation Evaluation in India and Kenya: Phase II Report: An Outcome Evaluation of Six Generation Programs', Report submitted to Generation, Mathematica.

- International Labour Organization (2024), 'Labour Force Statistics database', ILOSTAT. Accessed 12 March, 2024.

- McKenzie, David (2017), "How Effective are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing Countries? A Critical Review of Recent Evidence", The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2): 127-154.

- Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (2023), 'State-wise and District- wise Candidates Trained and Placed under PMKVY since 2015 to 31.03.2023'.

16 July, 2025

16 July, 2025

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.