Economics continues to be among the male-dominated disciplines in the US and Europe. Collating and analysing data from India on university faculty, research presentations at a major annual conference, and journal publications, this article examines the gender gap in academia in the field of economics.

Economics continues to be among the most male-dominated disciplines in the US and Europe. Lower share of women in economics, starting at the undergraduate level and persisting in faculty and research positions at prestigious institutes, continue to be a reality in American and European universities (Ginther et al. 2017, Aurio et al. 2019, Lundberg and Stearns 2019). This is striking in a context where several of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) disciplines have seen a considerable reduction in the gender gap over the years (Bayer and Rouse 2016).1 A number of institutional and non-institutional factors have been pointed out that may either cause or exacerbate this gender gap in economics (Bayer and Rouse 2016, Wu 2018).

Why is the presence of women (or other disadvantaged groups) in academia important? Other than pertinent normative considerations, there is also growing evidence that the background of the researcher matters for what topics are studied, and how they are studied. For example, May et al. (2014) found differences in the views of female and male economists on issues such as equal opportunity in the labour market, minimum wages, and gender wage gaps, among other topics. Diversity, thus, is expected to lead to different perspectives, methods, and questions within the discipline. This is crucial for a discipline like economics that has a strong influence on public policy (Mester 2019).

In our ongoing research (Dongre, Singhal and Das 2020), we explore the representation of women in economics academia in India by focussing on three dimensions. First, we look at presence of women with economics doctorates among regular, full-time faculty (excluding visiting, adjunct, and honorary faculty) in ‘elite’ institutions offering postgraduate/diploma programmes.2 Data have been gathered from the official websites of 120 such institutions spread across India, between May 2019 and February 2020. The second dimension that we study, is presenting research at a prestigious conference. Specifically, we manually compiled individual author-level data from over 1,300 papers that were presented at the ‘Annual Conference on Growth and Development’ between 2004 and 2017, hosted by the Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi (ISI-D). This is analogous to Chari and Goldsmith-Pinkham (2017) who studied the share of female authors represented at the prestigious National Bureau of Economics Research (NBER) Summer Institute Conference between 2001 and 2016.3 The third dimension that we focus on is publications in peer-reviewed journals. We focus on the share of women among the authors whose works have been published in the Indian Journal of Labour Economics (IJLE) since most of the articles published in the IJLE are by the researchers affiliated with Indian institutions.4

Women in economics academia in India

Out of all faculty members holding a Ph.D. in economics and teaching at elite institutions in India, 29.6% are women. This share is lowest at the full professor level at 25%, while it is 33% at the level of assistant and associate professor.5 We find substantial heterogeneity across institutions – notably, the share of women faculty (especially full professors) is lowest at the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), institutes of national importance, and central universities, and conversely, state universities and private universities have higher shares (see Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage of female faculty by type of the institution

|

Institution type |

Number of faculty members |

Assistant professor |

Associate professor |

Professor |

Overall |

|

Central universities (Public) (n=13) |

Female faculty |

16 |

6 |

15 |

39 |

|

Total faculty |

63 |

25 |

87 |

178 |

|

|

% Female |

25.4 |

24 |

17.24 |

21.91 |

|

|

State universities (Public) (n=34) |

Female faculty |

31 |

15 |

37 |

83 |

|

Total faculty |

77 |

40 |

111 |

228 |

|

|

% Female |

40.26 |

37.5 |

33.33 |

36.4 |

|

|

Deemed to be university (n=12) |

Female faculty |

14 |

7 |

12 |

33 |

|

Total faculty |

35 |

17 |

42 |

94 |

|

|

% Female |

40 |

41.18 |

28.57 |

35.11 |

|

|

Institution of national importance (n=19) |

Female faculty |

15 |

6 |

6 |

27 |

|

Total faculty |

53 |

30 |

41 |

124 |

|

|

% Female |

28.3 |

20 |

14.63 |

21.77 |

|

|

Private universities (n=9) |

Female faculty |

17 |

7 |

6 |

30 |

|

Total Faculty |

35 |

9 |

18 |

62 |

|

|

% Female |

48.57 |

77.78 |

33.33 |

48.39 |

|

|

Indian Institute(s) of Management (IIMs) (n=13) |

Female faculty |

12 |

7 |

6 |

25 |

|

Total faculty |

39 |

24 |

37 |

104 |

|

|

% Female |

30.77 |

29.17 |

16.22 |

24.04 |

|

|

Other standalone institutions (n=14) |

Female faculty |

11 |

5 |

8 |

25 |

|

Total faculty |

30 |

15 |

29 |

76 |

|

|

% Female |

36.67 |

33.33 |

27.59 |

32.89 |

|

|

Institutions recognised by university (n=6) |

Female faculty |

5 |

3 |

10 |

16 |

|

Total faculty |

25 |

8 |

41 |

73 |

|

|

% Female |

20 |

37.5 |

24.39 |

21.92 |

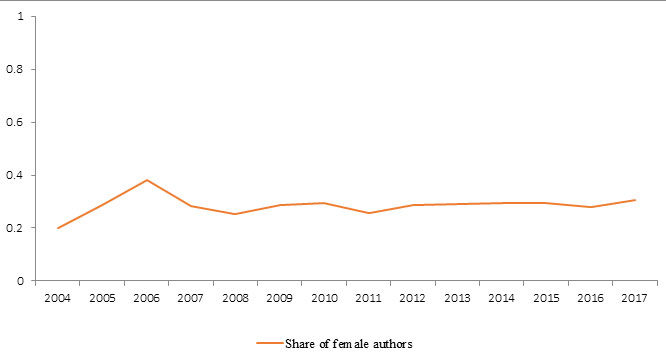

Our findings from the ISI-D conference data show that women constitute about 29% of the authors of papers presented at the conference between 2004 and 2017. However, there is no visible improvement over time (see Figure 1).6

Figure 1. Share of female authors of papers presented at conference

When it comes to publication in the IJLE, the share of female authors is 26.4% over the entire period of 2004-2017. The share has increased from 24.4% between 2004 and 2010 to 31% between 2011 and 2017.

What is keeping women away?

Is the low share of women economists in Indian academia driven by their low share at the masters and the Ph.D. level? In order to explore this possibility, we compiled information on share of female students at the masters- and the Ph.D.-level courses in economics across India (using MHRD data), and specifically for certain elite institutions through data gathered manually (websites, annual reports, and requests made under the Right To Information Act). We also gathered information on the share of female Indian citizens enrolled in doctorate programmes in the US – the most sought-after destination outside India for an economics doctorate.7

We find that women constitute more than half of the students at the masters level in economics programmes across India for the period from 2011 to 2018 (see Table 2). This trend is similar across elite institutions such as Delhi School of Economics, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development and Research, Jawaharlal Nehru University and others where year-wise student-level data were available, with the exception of ISI (Delhi and Kolkata centres combined) that has had a share of females at around 40% over the years.

Table 2. Percentage of female students in economics masters programmes in India

|

Enrolment in postgraduate studies (%) |

Completed postgraduate studies (%) |

|

|

2011-12 |

52 |

52 |

|

2012-13 |

54 |

56 |

|

2013-14 |

54 |

56 |

|

2014-15 |

55 |

53 |

|

2015-16 |

56 |

57 |

|

2016-17 |

57 |

59 |

|

2017-18 |

56 |

60 |

Share of women at the Ph.D. level in India was at around 40% till 2014-2015.8 This is at least 10 percentage points lower than the share of women in master’s programmes. The figure is moving closer to 50% in more recent years for which data are available. Among Indian citizens who hold doctorates in economics from the US, the share of women has increased from about 40% between 1997 and 2010, to around 50% in the 2010-2017 period.9 Overall, there is an encouraging trend of women approaching an equal share at the doctoral level.

But do those who complete their Ph.D. abroad return to India? We tracked the career trajectories of individuals who passed out of one the most coveted economics master’s programmes in India. It reveals that conditional on obtaining their doctoral degree outside India, women are more likely to continue to stay abroad relative to men.10 Given that an increasingly larger share of faculty in elite institutions in India have doctorates from institutions abroad, this could partially explain the lower share of women faculty in elite institutions in India.

To get some sense of what transpires post-Ph.D., we spoke to a few Indian women who have completed their Ph.D. in economics. These women mentioned family and childcare responsibilities as an important reason for not being in the labour force and/or not being able to pursue research that can be presented in a conference or be published in a journal. This was a very small sample, and hence, the findings from these interactions are suggestive and not necessarily representative.

Conclusion and areas for future research

We highlight lower representation of women in economics academia in India, and a few potential channels that are likely responsible for this trend. However, many more aspects of this issue are not completely known – Do women prefer non-academic jobs after their masters and doctoral studies?, Do women and men study different topics that have differential implications on their job market prospects?, Are there biases in the recruitment process at elite institutions?, To what extent do women quit the labour force post marriage or childbirth?, Are women less likely to participate in conferences because they are not ‘family-friendly’ (Bos et al. 2017); and what does the composition of women look like through a more intersectional lens, that is, when caste, region, economic background and other factors are added to the mix? Exploring these questions will help us understand the reasons for women’s under-representation in economics academia in India, and devise measures accordingly.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- Also see https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/usr15_is_the_gender _gap_narrowing_in_science_and_engineering.pdf

- ‘Elite’ institutions here refer to the ones that feature among the top 100 in the National Institution Ranking Framework (NIRF), an initiative of the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). For details, see Dongre, Singhal and Das (2020).

- Lack of access to similar data on other conferences, despite our efforts, has prevented us from including more conferences in our analysis, and hence, we would not advise generalisation solely on the basis of data from the ISI-D conference. ISI-D is an institute of national importance and their annual conference is among the biggest annual conferences hosted in India for presentation of economics research.

- We initiated a similar exercise for the Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics (AJAE) as well. However, we could not determine the gender of more than 30% of the authors based on the stated name, and hence we donot report those results. We do not consider the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) since it is a multi-disciplinary journal.

- In terms of seniority of position, university faculty ranks the positions as assistant professor, associate professor and (full) professor in ascending order of seniority.

- Please see Dongre, Singhal and Das (2020) for a more detailed analysis on this.

- Data from Survey of Earned Doctorates obtained from National Science Foundation.

- On a different note, our findings stand in contrast to the US, where the share of women at both these levels has been less than 35% (Buckles 2019).

- These data were obtained from the Survey of Doctorates, National Centre for Science and Engineering Statistics, National Science Foundation (NSF).

- Of those who completed their Ph.D. abroad, 42.9% male alumni and 24.4% women alumni are currently in India. See Dongre, Singhal and Das (2020)

Further Reading

- Auriol, E, G Friebel and S Wilhelm (2019), ‘Women in European Economics’, Working paper.

- Bayer, Amanda and Cecilia Elena Rouse (2016), “Diversity in the Economics Profession: A New Attack on an Old Problem”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4): 221-42.

- Bos, Angela L, Jennie Sweet-Cushman and Monica C Schneider (2019), “Family-friendly academic conferences: a missing link to fix the “leaky pipeline”?”, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(3): 748-758.

- Buckles, Kasey (2019), “Fixing the Leaky Pipeline: Strategies for Making Economics Work for Women at Every Stage”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(1): 43–60.

- Chari, A and P Goldsmith-Pinkham, ‘Gender Representation in Economics Across Topics and Time: Evidence from the NBER Summer Institute’, NBER Working Paper No. 23953.

- Dongre, Ambrish, Karan Singhal and Upasak Das, ‘Presence of Women in Economics Academia: Evidence from India’, ArXiv:2011.00366, Cornell University.

- Ginther, DK, S Kahn and J McCloskey (2017), ‘Gender and Academics’, in M Vernengo, EP Caldentey and BJ Rosser Jr (eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.

- Lundberg, Shelly and Jenna Stearns (2019), “Women in Economics: Stalled Progress”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(1): 3–22.

- May, Anne Mari, Mary G McGarvey and Robert Whaples (2014), “Are Disagreements Among Male and Female Economists Marginal at Best?: A Survey of AEA Members and Their Views on Economics and Economic Policy”, Contemporary Economic Policy, 32(1): 111–132.

- Mester, L (2019), ‘Increasing Diversity, Inclusion, and Opportunity in Economics: Perspectives of a Brown-Eyed Economist’, Second Annual Women in Economics Symposium, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- Wu, Alice H (2018), “Gendered Language on the Economics Job Market Rumors Forum”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 175–79.

05 March, 2021

05 March, 2021

By: Padmakar Kamble 05 March, 2021

Just I have read this... What is the percentage of (representation) of SC/ST/OBC category women, as a faculty in higher educational institutions in India?