In the seventh post of I4I’s month-long campaign to mark International Women’s Day 2023, Madeline McKelway and Julia Redstone outline the findings of a study investigating the empowerment effects on married women of an employment opportunity in carpet weaving in Uttar Pradesh. They note that although the intervention increased women's participation in the training programme and involvement in household decision making, the employment effects were not long-lasting, as participation in paid work came at the cost of women's leisure time.

Join the conversation using #Ideas4Women

Empowering women is often seen as a way to promote development, but is also valuable in itself (Kabeer 1999, Duflo 2012). Global leaders have recognised the inherent value of female empowerment with the fifth Sustainable Development Goal: to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” (UN General Assembly, 2015). There are many definitions of women’s empowerment, but they generally involve women’s ability to make choices (Kabeer 1999, Malhotra et al. 2002). One area where many women in developing countries experience a lack of autonomy and bargaining power is within marriage and the household (Jayachandran 2015). This matters both for women’s wellbeing and for development, as many key economic decisions are made by households.

Expanding women’s employment opportunities is widely seen as a way to empower them (World Bank, 2012, Heath and Jayachandran 2018). Economic theory posits that women’s control in the household should increase as opportunities for them to earn income improve (Browning and Chiappori 1998). Although there is evidence that supports this hypothesis (see Qian 2008, Anderson and Eswaran 2009, Atkin 2009, Majlesi 2016,), these studies use few direct measures of empowerment and are mostly non-experimental.

Field experiment

A recent study (McKelway 2023) uses a field experiment in rural Uttar Pradesh, India, to study how employment opportunities affect the empowerment of married women. In addition to the standard questions on who makes decisions in the home, the study uses incentivised choices and psychosocial measures to capture empowerment. India’s female labour force participation rate is one of the lowest in the world (World Bank, 2020) and gender inequality in India is higher than other countries (Jayachandran 2015). Uttar Pradesh in particular has some of the highest levels of gender inequality and poverty (National Institution for Transforming India, 2018).

The study was conducted in partnership with Obeetee, one of India’s largest carpet producers. In 2015, the firm started a programme offering women four months of paid training in carpet weaving, followed by long-term weaving employment for those who complete training. The training pay is substantial – close to what women ultimately earn as weavers – and both training and employment occur in all-female weaving centres located in the women’s villages. An earlier study (McKelway 2022) found that participation in the programme, and employment more generally, was correlated with greater levels of empowerment for women; the newer research seeks to understand the causal effects.

The sample for the experiment included several hundred married women, aged 18 to 40, who would be eligible to participate in Obeetee’s female weaving programme when it began in their villages. Just 15% of the sample was employed when the experiment began.

As part of the experiment, a video promoting the female weaving programme was shown to women’s husbands and parents-in-law. These family members often have a great deal of control over women’s employment in India (Bernhardt et al. 2018; Khanna and Pandey 2020, Field et al. 2021; Lowe and McKelway 2022), and prior research in this setting suggests husbands tend to be less supportive of women working outside the home than their wives (Lowe and McKelway 2022). The video was six minutes long, and included testimonials from individuals involved in the programme, in addition to images of the workplace. The speakers featured in the video – programme supervisors, female weavers, and a weaver’s husband – discuss the merits of the programme from their perspective. The research team gave all women basic details about the programme and showed the video to them. Treatment assignment determined what information the team gave to family members: treated family members were given job details and shown the video, while control family members were only given job details.

Women’s participation in paid employment

The treatment was successful in making family members view the weaving programme more favourably. To measure this, family members’ opinions on basic aspects of the programme were assessed just after they were informed about it and aggregated – the treatment increased an index of favourable opinions on the programme by 0.393 standard deviations1. This effect is driven by more favourable opinions on the pay, hours, work stability, and workplace facilities. On the other hand, the treatment didn’t affect attitudes about the social acceptability of women’s work, or beliefs that women may gain more control in the household as a result of participating in the programme.

Accompanying these favourable effects on beliefs was a large effect on women’s participation in the programme. Four months after the intervention, and three months into the programme’s training phase, only 11.2% of women in the control group had ever participated in the programme. The treatment increased this by 8.3 percentage points – a nearly 75% increase.

Therefore, the treatment can be interpreted as having changed household beliefs about women engaging with employment opportunities, and made family members recognise that desirable jobs for women do exist. At the same time, it does not appear to have shifted beliefs in a way that would have affected women’s empowerment through other channels.

Effects on household decision-making

Economic theory would suggest that changes in beliefs around employment could grant women more control in their households (Browning and Chiappori 1998). In theory, changing availability and assessments of female job opportunities could raise women’s control even if women didn’t start work – just the possibility that they could work should improve their bargaining position in their households – and taking up work could compound the effect by developing women’s skills and employability.

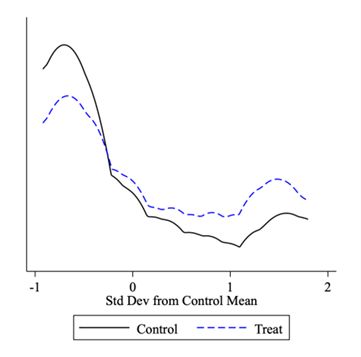

Did the treatment give women more control in their households? A survey done four months post-intervention asked women questions about who in their households made seven different sorts of decisions. The treatment increased an index of women’s involvement in these decisions by 0.184 standard deviations (Figure 1).2

Figure 1. Kernel densities of index of women’s involvement in decisions

Note: A kernel density plot is a visual representation of how the values of a variable (in this case, the index which shows the extent to which women decide) are distributed across the sample. The sample size is 390.

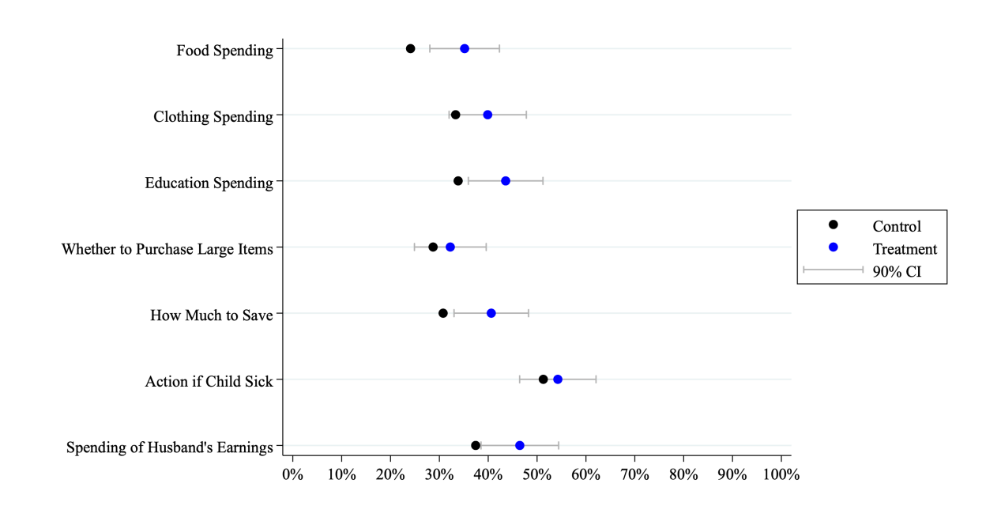

Looking at effects on involvement in each decision individually shows significant increases in women’s involvement in decisions about spending on food, spending on children’s education, how much to save, and how their husbands’ earnings should be spent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effects of intervention on women’s reporting of making particular decisions

Notes: i) The sample sizes (from top to bottom) are 390, 390, 389, 390, 390, 389, and 390. ii) A 90% confidence interval (CI) indicates that if you were to repeat the study over and over with new samples, 90% of the time the true effect would be within the interval.

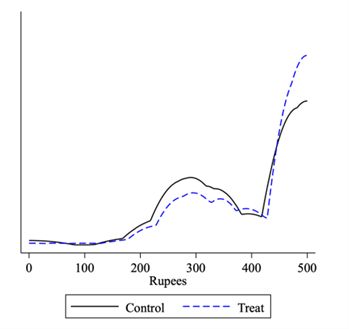

Women’s empowerment in economic decision-making was also measured through incentivised choices women made during the four-month survey. Women were entered into a lottery with a prize of Rs. 500, allocated across bangles, men’s sunglasses, women’s sarees/salwar suits, and men’s pants/kurtas as per the winner’s choice. During the survey, women had to choose the prize they would want if they won. On average, women in the control group allocated Rs. 411 to women’s goods – the treatment increased this by Rs. 20, a 0.175 standard deviation increase (Figure 3). This greater willingness of women to allocate money towards items for themselves could represent a shift towards more empowered preferences.

Figure 3. Kernel densities of women’s spending on women’s goods

Note: A kernel density plot is a visual representation of how the values of a variable (in this case, the amount spent on women’s goods) are distributed across the sample. The sample size is 356.

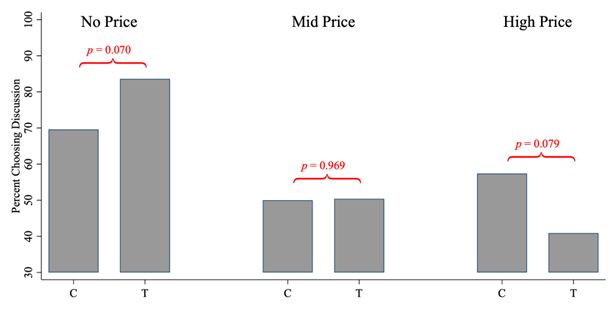

Effects on a second incentivised choice provide further evidence of the treatment increasing women’s empowerment in household decision-making. For the prize in a second lottery, women chose between their husbands’ independent allocation of Rs. 500 across the four goods, or an allocation of Rs.500 minus P that their husbands would choose after a discussion with the women (where P represents the ‘price of discussion’, and was randomly set at Rs. 100, Rs. 50, or zero). The treatment made women more likely to choose to discuss when there was no price, but less likely to choose discussion at the highest price (Figure 4). In theory, greater control in the household could make women more or less likely to choose discussion: assurance of greater control in that discussion could lead them to choose that option, while greater control of resources outside the discussion could make discussing this particular allocation not worth the time and effort. The more money to be allocated for the discussion, the stronger the first force would be. The treatment giving women greater control in the household could thus explain this pattern of effects.

Figure 4. Likelihood of choosing to discuss with husbands, by price of discussion

Notes: i) C and T indicate the percentage among the control and treatment groups respectively. ii) The sample size for this task is 353. iii) The p-values are the probability of getting results at least as extreme as the results observed, given the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. A p-value lower than a specified significance level (in this case, if p < 0.1) would be considered statistically significant.

On the other hand, the treatment didn’t shift psychosocial dimensions of empowerment even after four months. The study finds no effects on women’s or family members’ gender attitudes. In terms of mobility, the treatment increased the amount of time women spent outside of their homes, but not if time spent on paid work is excluded. The paper also finds no effects on women’s self-efficacy or aspirations. One potential explanation is that it takes more than a few months for female employment opportunities to move social attitudes or women’s psychology.

What activities were crowded out by the time women spent working? The treatment did not significantly affect time women spent on household chores, but significantly decreased their leisure time. Remarkably, the sample averaged over eight hours a day on chores. Responsibilities in the home presumably made employment challenging for women; indeed, having too many chores was by far the most common reason cited for women dropping out of Obeetee’s programme, and the effect of the treatment on employment had faded after one year. Over 80% of women believed a woman’s main role should be to tend to housework and the treatment did not affect this, which could explain why unpaid labour was not reallocated in the household even when women had gained more control.

While empowering women is valuable in itself, much interest in it stems from the idea that it could promote development, by increasing investments in children, for example (Kabeer 1999, Duflo 2012). The study finds suggestive evidence that the treatment increased investments in girls’ studies. In the week before the four-month survey, 43.7% of daughters in the control group had studied outside of school, either independently or through tutoring. The treatment increased this figure by 8.3 percentage points, though the effect is not quite statistically significant.

Conclusion

Results suggest that employment opportunities do raise women’s empowerment in household decision-making, measured using both survey questions and incentivised choices. On the other hand, psychosocial dimensions of empowerment were largely unaffected, at least over a short time horizon. Employment appears to have come at the cost of women’s leisure time rather than reducing time spent on household chores, which may explain why effects on employment did not last.

From a policy perspective, these results suggest female employment opportunities can indeed empower women and thereby help to achieve the fifth Sustainable Development Goal. However, low job retention of women may discourage firms from creating positions for them. Future research should investigate what can keep women in the labour force: improving retention may both increase the availability of jobs for women and generate strong, persistent gains in their empowerment.

Notes:

- Standard deviation is a measure used to quantify the amount of dispersion in a sample of values from the mean value of that sample. To form the index, each variable reflecting a favourable opinion on a basic aspect of the programme was converted into units of standard deviations from the control group mean. Those variables were then averaged, and the index was formed by converting the average into standard deviations from the control group mean.

- This index was formed analogous to the index of favourable opinions on the programme.

Further Reading

- Anderson, Siwan and Mukesh Eswaran (2009), “What Determines Female Autonomy? Evidence from Bangladesh”, Journal of Development Economics, 90: 179-191.

- Atkin, D (2009), ‘Working for the Future: Female Factory Work and Child Health in Mexico’, Working Paper

- Bernhardt, Arielle, Erica Field, Rohini Pande, Natalia Rigol, Simone Schaner and Charity Troyer Moore (2018), “Male Social Status and Women’s Work”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 363-367.

- Browning, Martin and Pierre-Andre Chiappori (1998), “Efficient Intra-Household Allocations: A General Characterization and Empirical Tests”, Econometrica, 66(6): 1241-1278.

- Duflo, Esther (2012), “Women Empowerment and Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4): 1051-1079.

- Field, Erica, Rohini Pande, Natalia Rigol, Simone Schaner and Charity Troyer Moore (2021), “On Her Own Account: How Strengthening Women’s Financial Control Impacts Labor Supply and Gender Norms”, American Economic Review, 111(7): 2342-2375.

- Heath, R and S Jayachandran (2018), ‘The Causes and Consequences of Increased Female Education and Labor Force Participation in Developing Countries”, In SL Averett, LM Argys and SD Hoffman (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Jayachandran, Seema (2015), “The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries”, Annual Review of Economics, 7(1): 63-88.

- Kabeer, Naila (1999), “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment”, Development and Change, 30(3): 435-464.

- Khanna, M and D Pandey (2020), ‘Reinforcing Gender Norms or Easing Housework Burdens? The Role of Mothers-in-Law in Determining Women’s Labor Force Participation’, Working Paper.

- Lowe, M and M McKelway (2022), ‘Coupling Labor Supply Decisions: An Experiment in India’, Working Paper.

- Majlesi, Kaveh (2016), “Labor Market Opportunities and Women’s Decision Making Power within Households”, Journal of Development Economics, 119: 34-47.

- Malhotra, A, SR Schuler and C Boender (2002), ‘Measuring 24 Women’s Empowerment as a Variable in International Development’, Background Paper prepared for the World Bank Workshop on Poverty and Gender: New Perspectives.

- McKelway, Madeline (2022), "Women's Employment and Empowerment: Descriptive Evidence", AEA Papers and Proceedings, 112: 541-545.

- McKelway, M (2023), ‘Experimental Evidence on the Effects of Women's Employment’, Working Paper.

- National Institution for Transforming India (2018), ‘SDG India Index’.

- Qian, Nancy (2008), “Missing Women and the Price of Tea in China: The Effect of Sex Specific Earnings on Sex Imbalance”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3): 1251-85.

- UN General Assembly (2015), ‘Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1’.

- World Bank (2012), ‘World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development’, World Bank.

17 March, 2023

17 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.