Adolescent girls in rural Rajasthan frequently leave education early and marry young. This article develops a novel methodology to elicit average parental preferences over a daughter's education and age of marriage, and subjective beliefs about the evolution of her marriage-market prospects. It finds that prospects of finding a desirable groom are an important driver of girls’ education. Policies that help girls stay in school can prevent early marriage.

Adolescent girls in rural Rajasthan, India frequently leave education early and marry young – a third of girls are out of school by age 16 and a third are married by age 18 – with worrying implications for their later welfare (Duflo 2012). In a context where young women have little influence over their marriage and schooling, understanding what drives parents’ decisions is crucial to predict the impacts of policies aimed at delaying school dropout and marriage.

Marriage-market returns

Investments in schooling are often rationalised by their associated labour-market returns. However, this motive is likely weak in rural Rajasthan – very few women work for pay and, in any event, womens wages accrue to the family of her husband rather than to her own parents. Rather, marriage is arguably the most important determinant of a woman’s future and well-being in this setting.

The age and schooling of young women might affect their chance of marrying a desirable groom (Chiappori et al. 2015, Attanasio and Kaufmann 2017). If parents care about the quality of their daughter’s marriage, for altruistic or other reasons, these 'marriage-market returns' might influence schooling decisions and the age at which a suitable match is searched for.

In recent research (Adams and Andrew 2019), we find that a key motivation for parents to educate daughters is the belief that education will increase her chance of marrying a well-paid and securely-employed man. Outside of this marriage-market advantage, parents have only a weak preference for educating adolescent girls. With other things equal, parents would prefer to delay their daughters’ marriages until age 18; parents perceive that a young woman’s marriage prospects worsen with every year she is out of school. Our results imply that policies that help families to keep daughters in school should have large knock-on effects at reducing early marriage.

The methodology: Novel survey design to understand decision-making about sensitive topics

Quantitative evidence on parents’ decision-making in this context is hard to find. Many different factors are at play, which are difficult to disentangle from data on marriage patterns and completed education alone. For example, does early school drop-out reflect a lack of value placed on girls’ schooling by her parents, a belief that ‘over-education’ hinders her ability to achieve a good marriage, or shocks to the household’s situation that make it hard for a girl to remain in school?

Does an early marriage reflect a preference for marrying daughters’ early or a belief that she is unlikely to receive as good a marriage offer again? Further, these are sensitive topics; marriage before 18 and payment of dowry are technically illegal but both are common, leading to misreporting in standard surveys.

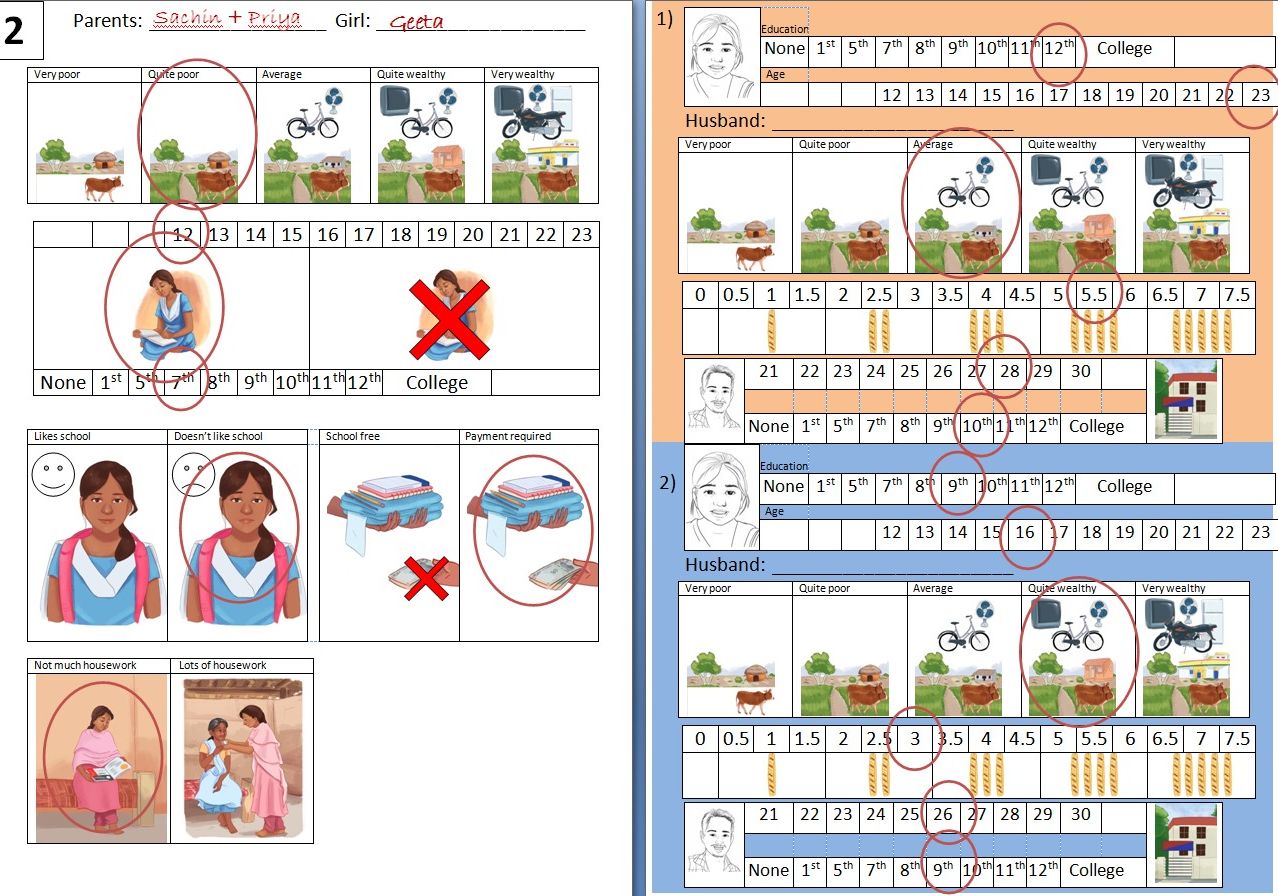

In our study, we designed two types of survey instruments to understand parents’ preferences and beliefs in a culturally sensitive manner. Both instruments use vignettes about hypothetical families that are described to live in a village similar to that of the respondent.

In a first ‘ex-post’ experiment, we describe the parents of a 12-year-old girl, giving details about the family’s wealth and circumstances. Respondents are asked to imagine that there are two possible options for the daughter’s schooling and marriage. Each option varies in completed education, age of marriage, and potential groom options. Respondents are asked which option they think the hypothetical parents would choose.

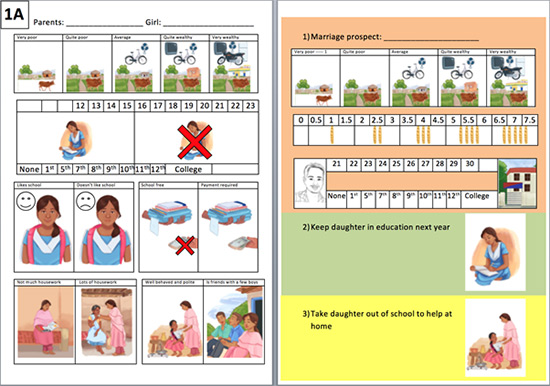

Figure 1 shows an example of a marked-up visual aid used to help respondents keep track of the vignettes. As the characteristics of the groom are specified in the vignettes, considerations about how education and age might affect who a girl can marry are not relevant here.

Figure 1. Visual aid to help parents respond to possible options about their daughter’s age of marriage and education, and groom characteristics

By carefully varying the characteristics of the hypothetical family, grooms, and the age of marriage and education level of the daughter, we are able to recover parents’ preferences over girl's age of marriage, education level, and the characteristics of her eventual husband.

The findings: Parents’ strongly prefer to delay marriage until age eighteen but place little intrinsic weight on girls’ education

Age and education at marriage

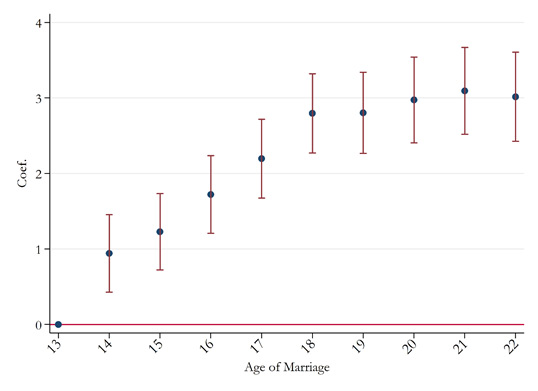

We find that parents have a strong preference for delaying a daughter’s marriage until age 18 (the legal minimum age of marriage for women) but no further (Figure 2a). While parents prefer to educate a daughter until the end of high school, this preference appears weak relative to preferences over age of marriage. Indeed, we find that parents dislike post-secondary education, a result that may be driven by its higher costs.

A desirable groom

When it comes to what constitutes a good quality marriage match, the overwhelming driver of preferences is whether a groom has a government job, which is the best paid and most secure form of employment in this area.

Figure 2. Parents’ preferences over daughter’s age and education at marriage

Parents believe that education greatly increases the chances of a girl achieving a good marriage

To measure beliefs about how a girl’s’ age and education impacts her chance of receiving a good quality marriage offer, we use a second set of vignettes. In these 'ex-ante' vignettes a hypothetical family is again described but the decision they face is whether to accept a particular marriage offer at a given point in time (for example when their daughter is 16 years old and still in school) or whether to reject the marriage offer and either keep their daughter in school or take her out of school to help at home.

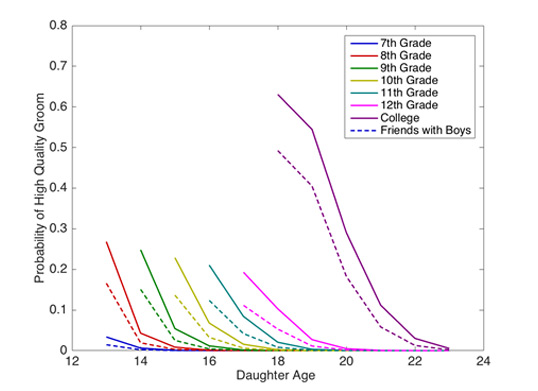

Figure 3 shows the visual aid in this case. Importantly, if parents reject this marriage offer, they don’t know with certainty what offers will occur in the future. Since we know how parents value age of marriage, education, and groom characteristics from the first experiment, we can use how respondents answer these vignettes that contain uncertainty to reveal what respondents believe about the likelihood of receiving marriage offers from desirable grooms in the future.

Figure 3. Visual aid used to elicit what parents believe about the likelihood of receiving marriage offers from desirable grooms in the future

Marriage-market returns of education

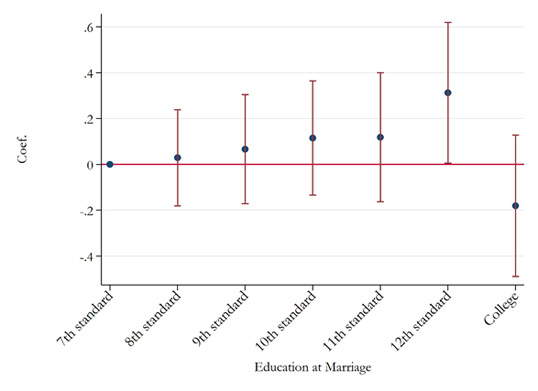

We find that parents believe there to be a substantial positive marriage-market return to a daughter’s education. While parents believe that a girl in college has a 60% chance of receiving a marriage offer from a groom with a government job, this probability is negligible for young women with only primary schooling. However, parents believe that this marriage-market return to education does not persist long after a daughter has dropped out of school; parents believe her marriage prospects quickly decline once she has left school.

Gender norms

Further, parents believe that girls whose behaviour breaks traditional gender norms are less likely to receive high-quality marriage offers. When daughters were described as being “friends with some boys and sometimes staying out of the house until late”, respondents were more likely to accept the marriage offer in hand, regardless of its quality, implying they perceived a marriage-market penalty for such young women. We find that these patterns are validated by more traditional approaches to eliciting beliefs.

Figure 4. Parents’ beliefs about marriage-market return on daughters’ education, and a perceived marriage-market penalty

Policy implications

Early marriage

Our findings highlight that positive marriage-market returns to young womens education increase the demand for girls’ schooling and delay her marriage. This insight is likely important in explaining why access to education, girls’ completed education, and age of marriage have all increased substantially over the past 20 years.

They also highlight, however, that the negative marriage-market return to age after leaving school makes girls who have recently dropped out particularly vulnerable to early marriage. Our focus groups suggested that young women are thought to be more vulnerable to risks that affect her perceived suitability as a good wife when out of school. These risks include being a victim of sexual harassment or assault, engaging in consensual romantic relationships or friendships with boys, or her becoming loud and opinionated (Bandiera et al. 2018). Adverse selection might provide a further reason if the groom's side infer that young women who are still not married several years after leaving school have undesirable qualities. Ultimately, such preferences and inferences likely derive from tightly prescribed ideals of young womens' behaviour.

Conclusion: Improving access to education for girls

While substantial progress has been made in ensuring schools are accessible to young women, many barriers still exist; the costs of post-secondary education remain substantial for poor households, many remote communities lack safe school transport; and households often face few alternatives to pulling a daughter out of school when a family member is ill. Our findings imply that policies that help vulnerable households to keep girls in school, and strengthen opportunities for adolescents to return to formal education if their studies are interrupted, are in high demand. They would also go a long way in protecting India’s daughters against early marriage.

This column was published in collaboration with VoxDev: https://voxdev.org/topic/health-education/why-do-parents-invest-girls-education-evidence-rural-india

Further Reading

- Adams, A and A Andrew (2019), 'Preferences and Beliefs in the Marriage Market for Young Brides', Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Discussion Paper 13567.

- Attanasio, Orazio P and Katja M Kaufmann (2017), “Education choices and returns on the labor and marriage markets: Evidence from data on subjective expectations”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 140, 35-55.

- Bandiera, O, N Buehren, M Goldstein, I Rasul and A Smurra (2018), "The Economic Lives of Young Women in the Time of Ebola: Lessons from an Empowerment Program" Mimeo. Available here.

- Chiappori, P.-A., M Dias, and C Meghir (2015), ‘The marriage market, labor supply and education choice’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 21004.

- Duflo, Esther (2012), “Women Empowerment and Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, 50 (4): 1051-79. Available here.

07 August, 2019

07 August, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.