A growing body of evidence shows that Indian farmers use chemical fertilisers in an unbalanced manner, partly driven by differential subsidies across fertiliser types. Based on analysis of agricultural data from selected states, this article finds that at median levels of fertiliser use and prices, doubling the ratio of potassium-based to nitrogen-based fertilisers would raise yields by almost 5% - without increasing overall fertiliser expenditure.

For decades, India’s agriculture has relied heavily on the use of chemical fertilisers. The Green Revolution made fertilisers a central pillar of crop management, and sustained growth in fertiliser use has been a key factor in improving the yields of staple crops such as rice and wheat. Today, India is one of the largest consumers of fertilisers in the world, with large government subsidies fuelling widespread adoption and high application volumes. Beyond the obvious pressures on government budgets – the Indian government currently spends between US$10 billion and US$11 billion a year on fertiliser subsidies alone (Zaveri 2025) – the overapplication of chemical fertilisers can lead to environmental degradation through soil acidification and greenhouse gas emissions, and negatively impact biodiversity and human health.

In addition to overall high application levels, a growing body of evidence shows that Indian farmers use fertilisers in a highly imbalanced way (Bora 2022). Nitrogen-based fertilisers, particularly urea, are applied in far greater quantities than other essential nutrients such as phosphorus and potassium. High nitrogen use relative to other types of nutrients – a secular trend in Indian agriculture – has been further reinforced by differential subsidies across fertiliser types that distort optimal input choices by affecting relative prices (Chand and Pandey 2009, Chatterjee and Kapur 2017, Garg and Saxena 2022).

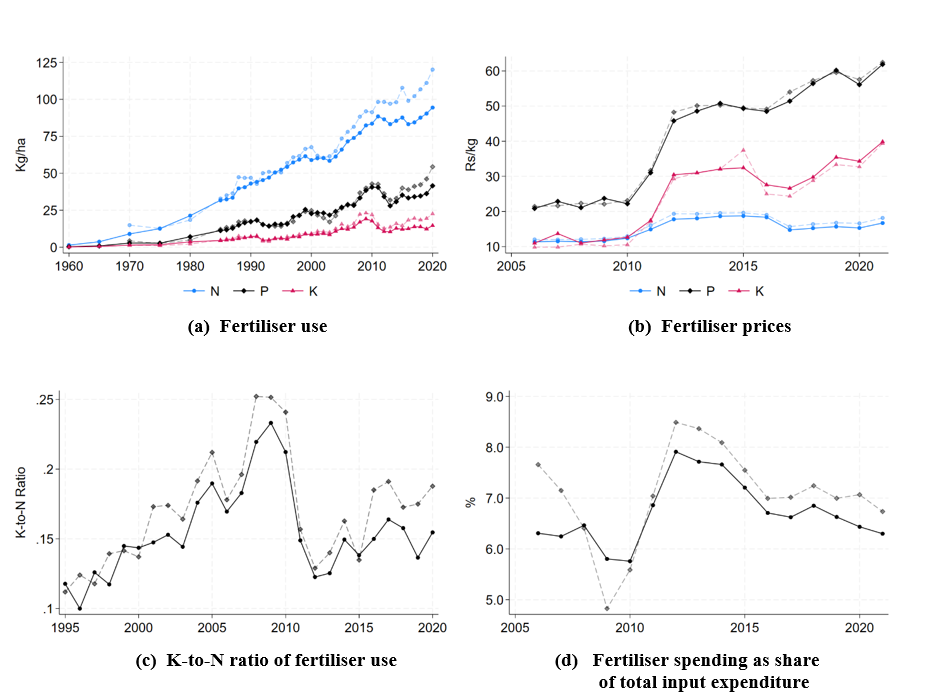

Figure 1. Fertiliser demand and price trends by nutrient

Note: Solid lines in all figures show nation-wide averages, while dashed lines represent averages for the states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and Odisha only.

Source: Panel (a): Fertiliser use by nutrient type based on data from the ICRISAT-TCI District-Level Database (DLD) for Indian Agriculture and Allied Sectors. Panel (b): Average fertiliser prices by nutrient (total expenditure/quantity applied) across cultivation units surveyed in each round of the Cost of Cultivation Surveys (CCS), 2006-2020. Panel (c): K-to-N ratio of potassium-based to nitrogen-based fertilisers based on data from DLD. Panel (d): Average expenditure on all types of fertilisers as a fraction of total agricultural input expenditures across cultivation units surveyed in the CCS. All prices are in nominal Indian rupees.

Fertiliser imbalance: New evidence from eastern India

To what extent could correcting these nutrient imbalances actually enhance agricultural production? In recent research (Arteaga and Deininger 2025), we investigate the effect that a more balanced application of nutrients – measured by the ratio of potassium to nitrogen applied to a field – would have on agricultural yields.

Our study drawing on detailed data from thousands of rice farmers in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and Odisha collected by several research teams affiliated with the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (Coggins et al. 2025). We first document that nitrogen application is almost eight times higher than potassium use, with rice farmers in the region typically applying over 120 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare but only about 15 kilograms per hectare of potassium. While the optimal proportions of nutrient application rates vary by crop and region, such large imbalances appear to be agronomically unsound given that the optimal use of fertiliser requires taking advantage of the complementary effects of different nutrients.

We then examine how much agricultural production would improve if these imbalances are corrected. Empirically, the main challenge in such an analysis is that fertiliser application choices are also related to other factors that also affect productivity. For example, better-off farmers might use both improved harvesting technologies and more balanced fertiliser ratios, leading to an observed positive relationship between fertiliser balance and higher yields that may not be causal. To overcome this issue, our study leverages the geographical particularities of India’s fertiliser supply chain. Nitrogen fertilisers such as urea are largely produced domestically in relatively few plants scattered across the country, usually in locations where natural gas is readily available. Potassium fertilisers, by contrast, are almost entirely imported and distributed through ports. This variation in geographical constraints in the supply chain of different types of fertilisers, serves as an “instrumental variable”1 that provides plausibly exogenous variation in the availability, relative costs, and application rates of different nutrients across Indian villages.

We find that adjusting the ratio of potassium to nitrogen (K-to-N) in fertiliser application could substantially increase rice yields even if farmers keep their overall fertiliser expenditure constant. A one-standard-deviation2 increase in the K-to-N ratio is associated with a 16% rise in yields. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that, at median levels of fertiliser use and prices, doubling the K-to-N ratio without increasing overall fertiliser expenditure would raise yields by almost 5%, equivalent to about 0.2 tonnes per hectare per season.

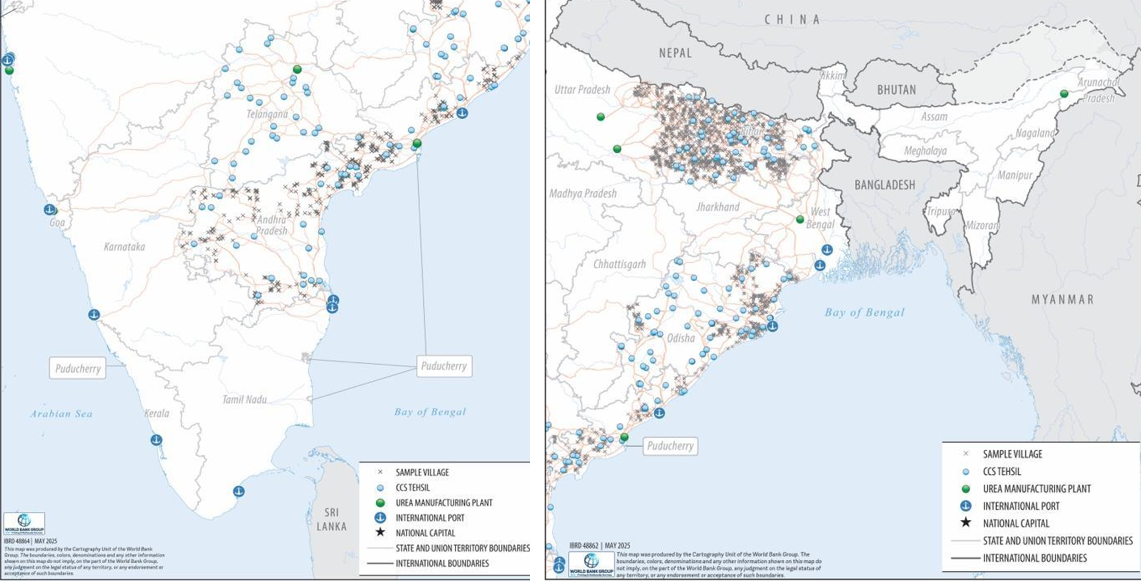

Figure 2. Minimum travel distances between sample villages, urea manufacturing plants, and international ports

Notes: Minimum road travel distances in kilometers between the closest urea manufacturing plant (green dots), and international port (dark blue dots) to each sample village in the CSISA-NUE dataset (crosses), and each sample tehsil in the CCS (light blue dots). Orange lines denote shortest route to a urea plant or to a major port.

Why do farmers not rebalance?

These results indicate that efforts to achieve a more balanced fertiliser use represent a significant opportunity for productivity gains in Indian agriculture. They also raise the question of why do fertiliser imbalances persist, despite the clear agronomic and economic benefits of correction. While price distortions remain the most visible obstacle, lack of information and risk aversion may also play a significant role. Fertiliser extension in India has historically emphasised nitrogen use, often presenting it as the primary determinant of higher yields, and many farmers are unaware of the complementary role of other nutrients. At the same time, market failures related to difficulties in assessing the reliability and effectiveness of agricultural inputs might lead to “adverse selection” in input markets and overall lower demand for potentially beneficial products.

To explore this question, we draw on a complementary survey of over 5,000 farmers in the state of Odisha that tests farmers’ general knowledge of fertiliser use and soil management. Based on farmers’ responses to this knowledge test, our study presents evidence suggestive of the fact that (i) farmers have, on average, very limited awareness of the role of potassium in crop growth, and (ii) farmers who demonstrate greater knowledge about the importance of potassium tend to achieve higher yields and revenues. Knowledge about fertiliser use and soil health is relatively low, with an average correct response rate of only 26%. Moreover, when it comes to knowledge of potassium-based fertilisers, only 45% of surveyed farmers could correctly identify fertilisers that supply potassium. Estimates for the association between higher farmer knowledge and their plot-level productivity show that farmers who are able to correctly identify potassium-based fertilisers tend to have plots with 1.3kilograms/hectare higher yields, producing Rs. 6,909.2/hectare per season more in net revenue. While correlational only, these associations hint at the importance of general fertiliser knowledge on better fertiliser use and, consequently, higher output levels. We take these results as indicative evidence of knowledge constraints being one of the main drivers of imbalances in fertiliser use.

Policy implications

Indian agriculture can achieve productivity gains not by increasing the volume of fertiliser use but by improving its balance. Correcting the composition of fertiliser use would help mitigate soil degradation, groundwater contamination, and emission of greenhouse gases. In this sense, policies that encourage nutrient balance offer a triple dividend: higher farm productivity, lower fiscal costs, and improved environmental outcomes.

Policymakers should consider recalibrating the current structure of fertiliser subsidies, as well as promoting educational campaigns that encourage farmers to adopt more balanced fertilisation practices. Improving the supply chain for potassium- and phosphorus-based fertilisers – such as via decentralised warehouses, better port connectivity, and timely distribution systems – could reduce availability constraints.

Perhaps the most cost-effective intervention lies in farmer education and extension services. The Odisha survey suggests that even basic awareness of potassium’s role can significantly improve yields. Strengthening extension services to emphasise nutrient balance rather than sheer fertiliser use could have large payoffs, and digital extension services could be used to disseminate practical, localised guidance on nutrient management – similar to successful interventions implemented in other agricultural contexts (Corral et al. 2020, Harou et al., Islam and Beg 2021).

Notes:

- An instrumental variable is selected such that it correlates with the explanatory variable, but does not directly affect the outcome of interest. It can therefore be used to measure the causal relationship between the explanatory variable and the outcome of interest.

- Standard deviation is a measure used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values from the mean (average) value of that set.

Further Reading:

- Arteaga, J and K Deininger (2025), ‘Yield Gains from Balancing Fertilizer Use: Evidence from Eastern India’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS 11134.

- Bora, Kaushik (2022), “Spatial patterns of fertilizer use and imbalances: Evidence from rice cultivation in India”, Environmental Challenges, 7: 100452.

- Chand, Ramesh and Lal Mani Pandey (2009), “Fertiliser Use, Nutrient Imbalances and Subsidies: Trends and Implications”, Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 3(4): 409-432.

- Chatterjee, Shoumitro and Devesh Kapur (2017), “Six puzzles in Indian agriculture”, India Policy Forum, 13(1): 185-229.

- Coggins, Sam et al. (2025), “Data-driven strategies to improve nitrogen use efficiency of rice farming in South Asia”, Nature Sustainability, 8: 22-33.

- Corral, C, X Giné, A Mahajan and E Seira (2020), ‘Appropriate Technology Use and Autonomy: Evidence from Mexico’, National Bureau Of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w27681.

- Garg, S and S Saxena (2022), ‘Redistribution through prices in Indian agricultural markets’, STEG Working Paper.

- Harou, Aurélie et al. (2022), “The joint effects of information and financing constraints on technology adoption: Evidence from a field experiment in rural Tanzania”, Journal of Development Economics, 155: 102707.

- Islam, Mahnaz and Sabrin Beg (2021), “Rule-of-thumb instructions to improve fertilizer management: Experimental evidence from Bangladesh”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 70(1): 237-281.

- Zaveri, E (2025), ‘Fixing Nitrogen : Agricultural Productivity, Environmental Fragility, and the Role of Subsidies’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS 11050.

06 November, 2025

06 November, 2025

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.