While the north Indian state of Punjab topped per-capita income rankings within the country until year 2000, its position fell consistently thereafter. In this post, Lakhwinder Singh, Nirvikar Singh and Prakarsh Singh discuss the current state of Punjab’s economy – in terms of agriculture, manufacturing and services; jobs and education; and public finance and governance – and the reasons for the challenges faced by the state. Further, they consider prospects for growth and enabling policies.

This is the fourth article in the Ideas@IPF2024 series

Punjab’s economy is characterised by slow growth, societal challenges, and environmental degradation. Some of Punjab’s recent economic trajectory has been shaped by its geography, including its position on an international border, and its water availability. The availability of water for agriculture was politically constrained by partitioning the region in 1947, and then by dividing Indian Punjab in 1966. The latter event occurred soon after national food security policy created a major shift in the state’s pattern of agriculture, towards a greater reliance on a wheat-rice crop cycle, tied to intensive use of water and fertilisers. Furthermore, Punjab’s position on the border with Pakistan, over a decade of conflict in the 1980s and 1990s, and proximity to Jammu and Kashmir constrained industrial investment and what might have been a typical progression of development in the state.

Early post-independence investments positioned Punjab well to be at the forefront of the national effort to achieve food security, built on new high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice, and a food procurement system that created an assured market for foodgrain – what popularly became known as the Green Revolution. However, subsequent development resulted in a mixed picture regarding growth of per capita income, reduction of poverty, provision of healthcare services and development of human capital. After the Green Revolution, the Punjab economy topped the rankings of per capita income among Indian states until 2000, but thereafter its ranking fell continuously – as of 2021-22, it is 10th among major Indian states.

Four interrelated factors constrain the Punjab economy. First, driven largely by dependence on the specific nature of the central government’s food procurement policy, the state remains heavily agricultural in a narrow manner. Second, Punjab’s fiscal situation is constrained in ways that make fiscal policy dysfunctional: related causal factors include the agricultural structure and the state’s political economy. Both physical and soft infrastructure have been negatively affected by the problems in public finances. Third, a combination of regional and domestic politics during an era of liberalisation disadvantaged the state, with existing manufacturing industries declining, and new industries and services not emerging rapidly enough. Fourth, both individual human capital and institutional or organisational capital have either failed to develop, or have deteriorated in some dimensions over recent decades, making Punjab less innovative and less attractive for new investment.

Economic structure

The share of agriculture and allied activities in GSVA (gross state value added) in Punjab based on advance estimates was 26.7% while the sector accounted for 24.6% of employment in 2022-23. Punjab’s share of agriculture had not declined much since the early 2000s and was higher than other Indian states with similar levels of per capita income. This reflects the unique structure of the Punjab economy: the state has only 1.5% of India’s area but contributes 31.2% of the rice and 46.2% of the wheat procured by the central government. These statistics highlight the central problem of Punjab agriculture, and of the state economy as a whole. Even within agriculture, diversification into less water-intensive crops, or into higher-value-added activities such as animal husbandry, has been inhibited. The reliance on growing wheat and rice for the national food procurement system has come with subsidies for water and electric power, which have contributed to environmental stress and an unsustainable fiscal situation. Patterns of fertiliser and pesticide use have also contributed to environmental problems, and mechanisation has reduced employment opportunities in agriculture.

The share of industry in Punjab’s GSVA is 27.4%, quite close to the share of agriculture in the state, and to the average share of industry for India as a whole. However, industry accounts for a higher employment share in the state than agriculture, at 34.3%. Gross capital formation (GCF) in industry is 31% of GSVA, fairly similar to the national figure, but has been shifting in relative terms from manufacturing to construction, within the industry sector. Growth of industry in Punjab has been higher than that of agriculture, and similar to the average for the country as a whole. Compared to the rest of India, Punjab has a higher proportion of registered versus unregistered manufacturing units, but it lacks large units, particularly when compared to states that have higher shares of manufacturing. Studies of Punjab manufacturing indicate a decline from the 1980s onward, some recovery in the early 2000s, but stagnation thereafter. Investment, technical efficiency, and productivity growth have been relatively low. Underinvestment is both a cause and consequence of the size distribution of firms, and even registered manufacturing firms are mostly very small.1 Access to reliable and low-cost electricity, workers with appropriate skills, and business credit are among the obstacles to growth. Furthermore, many industrial clusters in the state have lacked scale and adequate access to modern infrastructure and to markets.

Mirroring a pattern found across India, Punjab’s services sector is larger than agriculture or industry. It accounts for 45.9% of GSVA and 41.1% of employment. The sector has also grown faster than the others, over recent decades – again similar to the rest of India. One difference between Punjab and most other states at similar per capita income levels is that its agriculture sector is proportionately larger, and its services sector share is therefore considerably lower than the national average of 54%. However, Punjab’s service sector employs proportionately more of its workforce than the all-India average of 29%. This reflects the lower labour intensity of Punjab agriculture, relative to the rest of the country. While the state’s services sector is very heterogeneous, a significant fraction of its employment appears to be in trade and repair, versus other services sub-sectors (such as financial services and public administration) that might have higher productivity and growth potential. It is also not apparent that Punjab has adequate urban infrastructure and human capital for growth of those sub-sectors.

Labour and employment

For 2022-23, based on data from the Period Labour Force Survey (PLFS), Punjab’s labour force participation rate (LFPR) was considerably lower than the national average (53.5% versus 57.9%) and its unemployment rate was almost double the national average (6.1% versus 3.2%). Furthermore, the worker-population ratio in the state was much lower than the all-India figure (50.2% versus 56%). Compared to the rest of India, Punjab has higher unemployment rates, especially in the rural sector. There is a high demand for emigration, but also high immigration of unskilled workers from poorer states. The female LFPR in urban Punjab is similar to the national figures (23.2% versus 23.5%), but the differences in the rural sector are vast (26.3% versus 40.7%). This is consistent with the mechanised nature of Punjab agriculture and associated social norms. Youth of both genders are not doing agricultural work in ways that they would in a setting that is characterised by subsistence agriculture to a greater extent. The data suggest a situation where neither rural nor urban jobs are being created that fit the individual and social expectations of the population.

Education and health

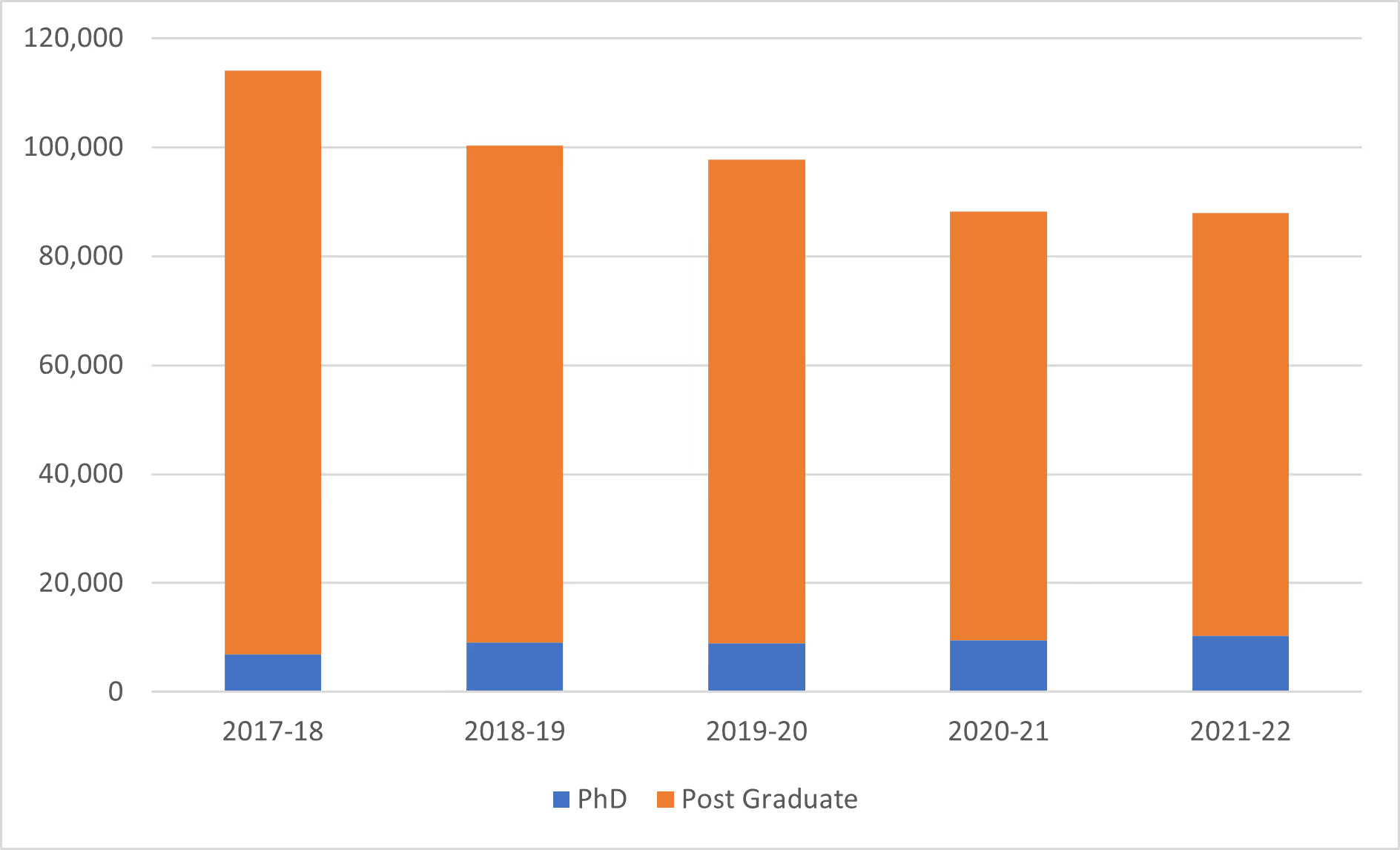

Punjab has a population of slightly over 30 million, with about one-fifth of this being of school-going age (5-18 years). Enrolment ratios are high, and dropout rates for primary education are low, but they rise more than for other better-off states in upper primary school and beyond. Approximately half of the school-going population attends government schools, which is similar to the national average. The ratio of students in government schools has increased slightly in recent years, arguably because of investments in school infrastructure. On some indicators of educational outcomes, Punjab has been the best-performing state in India of late. However, school teachers could be provided with performance-based incentives for achieving even better outcomes in language, mathematics, and science (Muralidharan and Sundararaman 2011). Similarly, school management systems (hiring, performance assessment, promotions, exit) could be re-evaluated for truly understanding the performance of teachers, and then acting on these. There is some suggestive evidence (Figure 1) that for education at higher levels (postgraduate), Punjab is showing a decline, which is almost entirely driven by women.

Figure 1. Number of postgraduates and PhDs in Punjab, 2017-18 to 2021-22

Source: All India Survey on Higher Education, 2021-22.

In many aspects of healthcare and health outcomes, Punjab does considerably better than the national average, though not necessarily better than other wealthier states. Life expectancy is just a few years more than the national figures, but Punjab’s statistics for prenatal and postnatal care, immunisation, malnutrition, and infant and child mortality are much better than those for India as a whole. This situation is a consequence of Punjab’s previous decades of prosperity, and reflects the durability of certain kinds of institutional development that occur in parallel with income and output growth. At the same time, the data indicate that Punjab’s rate of improvement is slowing down, and other states in India are catching up. Additionally, changes in lifestyles and nutrition associated with prosperity are having new, adverse impacts on health, especially among women and girls.

Public finances and governance

Punjab suffered from severe political and social turmoil from the early 1980s through the mid-1990s. During that decade-and-a-half, Punjab remained under President’s rule for much of the time. There was a significant shift of public expenditure from developmental purposes to the law-and-order machinery, which itself operated without checks and balances. The revenue collection machinery also collapsed, and state government borrowing rose dramatically. A revenue surplus turned into a revenue deficit, which has persisted. The gap between revenue receipts and revenue expenditure was Rs. 544 crores in 1990-91 and has risen consistently, such that the revenue deficit was Rs. 24,588 crores in 2022-23 – a five-fold increase after adjusting for inflation.

The state government’s debt burden as of March 2024 was 47.6% of GSDP (gross state domestic product), the highest among the major states of India. Since 2017, the state debt has risen at an annual average rate of more than 9%, with 92.2 % of the new borrowing being be used to service the existing debt in 2021-22. In effect, the Punjab government is in a debt trap. Meanwhile, revenue receipts continue to fall short of targets. In addition to low tax effort, low tax capacity is a major problem: Punjab is heavily agricultural, and that sector is exempted from direct taxes. Tax evasion, associated with declining government institutional capacity, is also a factor. Finally, non-tax revenue has also declined as a proportion of GSDP. Lack of institutional capacity, along with lack of incentives, also hinder collection of local property taxes, exacerbating the shortcomings of urban infrastructure. Indices of governance quality further suggest that the efficiency and effectiveness of governance have failed to improve (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Punjab Governance Index, 2002 and 2016

Source: Sodhi (2024).

Policy directions

Specific areas for policy action in Punjab include agricultural diversification, industrial development and innovation, cross-border services, and decentralisation to the local level. The state’s dire fiscal situation means that prospects for meaningful economic development will depend on collaboration between the state and national governments, including fiscal support from the latter to deal with accumulated public finance issues and the economic and political costs of switching to a different, more diverse economic structure.

While a major reform of the national food procurement policy has been announced, offering farmers unlimited purchases of maize and pulses at MSPs (minimum support price) if they switch from wheat or paddy, this may not be enough to incentivise large-scale changes in crop choices. Additional payments may be required, which could be justified politically as compensation for past contributions to national food security. For example, those payments can be earmarked for upgraded infrastructure for marketing or processing the crops to which farmers switch. A previous proposal, what was termed a Special Investment Deficiency Package (SIDP), would have supplemented the state government budget by about 20% a year for five years.

At a basic level, Punjab’s long-run economic growth will require a number of policy reforms to support industrial transformation. Business-owners require ‘ease of doing business’ at a very granular level, as numerous barriers remain beyond the initial step of government clearance – dealing with inspectors, enforcing contracts, accessing finance, finding skilled workers, and locating markets. In these areas, Punjab does worse than many other states, especially in the cost of electric power and the structure of taxes.

In addition to attending to current interconnected obstacles to economic growth, future sources of growth have to be envisioned. As economic growth becomes increasingly knowledge-intensive, Punjab’s economic structure appears more and more out of date. Much of the Punjab economy, in agriculture, manufacturing and services, involves activities and firms that are low productivity, low wage, and input intensive. The agriculture sector has had relatively high productivity compared to other Indian states, but because most of its output goes to national food procurement, there is very low value added beyond the farm gate. Many of Punjab’s subsectors in manufacturing and services are also low in value addition.

Punjab spends very little on research and development, in either the public or the private sector. Its universities are also falling behind, partly because of lack of financial resources, and partly due to organisational decline. Moreover, Punjab does relatively worse in higher education, though not at lower levels of education. All of these issues will have to be addressed if Punjab is to make any kind of transition to a knowledge economy.

In addition to investments in innovation and higher education, urban infrastructure needs serious attention. Punjab’s urban local governments are relatively weak, both fiscally and institutionally. Much of this situation is a consequence of the decline in state-level institutional quality and the deterioration of state government finances. Strengthening local governments financially and institutionally seems to be a necessary condition for creating high-value-added clusters in industry and services, along with investments in digital and other local infrastructure.

Conclusion

Lack of desirable employment, social problems such as drug and alcohol use, and the over-politicisation of religion all seem to stem from Punjab’s lock-in to the agricultural system created by the Green Revolution and an outdated national food procurement policy. The destruction of the groundwater table in Punjab, and potential desertification, will destabilise the state further, and have enormous national consequences. The original Green Revolution came from a national need for food security, and cooperation between the central and state governments. At the time, there was greater political alignment between the Centre and most state governments. The current political system may not be as well-equipped to achieve a new political bargain which replaces the one that originally made the Green Revolution system effective. However, realising that the economic, social and environmental situation in Punjab is a matter of national concern is the first step in working towards a new arrangement.

I4I is now on Substack. Please click here (@Ideas for India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- Many of these issues were analysed in Singh and Jain (2007). See also Verma and Kaur (2018) and Goyal (2020).

Further Reading

- Goyal, Kamlesh (2021), “Structural change and growth of manufacturing industries in Punjab: Post-reforms analysis”, Indian Journal of Economics and Development, 16(3): 389-396.

- Muralidharan, Karthik and Venkatesh Sundararaman (2011), “Teacher Performance Pay: Experimental Evidence from India”, Journal of Political Economy, 119(1).

- Singh, Lakhwinder and Varinder Jain (2007), “Growth and dynamics of unorganised industries in Punjab”, International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 1(1): 60-87.

- Sodhi, N (2024), ‘Governance in Punjab – A Policy Note’, Unpublished mimeo, Plaksha University.

- Verma, Satish, and Gurinder Kaur (2017), “Total Factor Productivity Growth of Manufacturing Sector in Punjab: An Analysis”, The Indian Economic Journal, 65(1-4): 91-106.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.svg)

.svg)

.svg)