The Lead Bank Scheme of the RBI involves a ‘lead bank’ in each district of India that coordinates financial services in the district, and a ‘convenor bank’ in each state that monitors these activities of the lead banks in the state. Analysing quarterly district-level data on credit disbursement for 2004-2019, this article finds that in districts for which lead bank and convenor bank belong to the same corporate entity, credit disbursement is 21% higher.

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) ‘Lead Bank Scheme’ is among the oldest financial inclusion programmes in the country. Initiated in 1969, the scheme assigns the role of lead bank to a public-sector bank in each district, based on the overall capabilities of the bank in the district. The lead bank coordinates with local financial-market agents to identify and address bottlenecks in the provision of financial services, and to conduct public outreach programmes such as financial literacy camps in the district. Further, another public-sector bank is assigned the role of convenor bank for the state, which involves monitoring the performance of lead banks of the state. The chairman of the convenor bank executes this function through quarterly meetings with lead banks. These meetings are regularly attended by senior bureaucrats and politicians of the state, and representatives of local press and NGOs (non-governmental organisations). If it is found that the lead bank has failed to meet targets, penalties are imposed, which may include allotting some funds to (low-yield) Rural Infrastructure Development Fund.

Given this organisational structure of the scheme, some districts have their lead and convenor banks belonging to the same corporate entity. What effect does this alignment have on the financial-market outcomes in the district? Theories of organisational economics suggest that lower costs of intra-firm monitoring and punishment, lead to higher effort by employees (Williamson 1981, Holmstrom 1999). In this context, the lead bank of an ‘aligned’ district should be exerting more effort as they are reviewed by their immediate supervisors. If so, one can expect higher credit disbursement in these districts.

For most public-sector banks in India, recruitment is conducted only for junior-level employees, whereas the senior positions, such as for lead bank personnel, are filled through promotions based on merit-cum-tenure. Further, attrition, and termination of employment remains low in these organisations. In such an environment, managers subject to review by their immediate superiors are more likely to exert higher effort in the assigned tasks.

If the personnel of the lead bank experience added organisational pressure from their own supervisors if the convenor bank belongs to the same corporate entity, then one can expect credit disbursement through branches of lead banks to be higher in ‘aligned’ districts, compared to branches of other banks in that district and branches of the same bank in non-aligned districts. However, data on branch-district level credit disbursement are not publicly available (see Acharya et al. 2019). Therefore, I test the hypothesis using RBI data on quarterly district-level credit disbursement, from 2003-04:Q4 (fourth quarter of the financial year) to 2018-19:Q4 (Gupta 2020). Nearly 44% of the districts are aligned. All else being equal, aligned districts should have higher credit disbursement, as monitoring by one’s own chairman should imply higher effort by lead bank personnel in aligned districts.

District ‘alignment’ and credit disbursement

My econometric analysis shows that aligned districts have 21% higher credit disbursement, on average, as compared to non-aligned districts, over the study period.

However, these two categories of districts could differ in terms of other characteristics – besides alignment – that influence credit disbursement. For example, the (unobservable) demand for credit may be higher in aligned districts. To address this issue, I analyze how credit disbursement changes in 38 districts, which experience a change in alignment. For these cases, the change in credit disbursement and alignment can be observed for a particular district, which overcomes a potential bias in the results induced by differences in unobservable district-specific characteristics. I find that for this group of districts, credit disbursement increases (decreases) by 28% when a district becomes aligned (non-aligned).

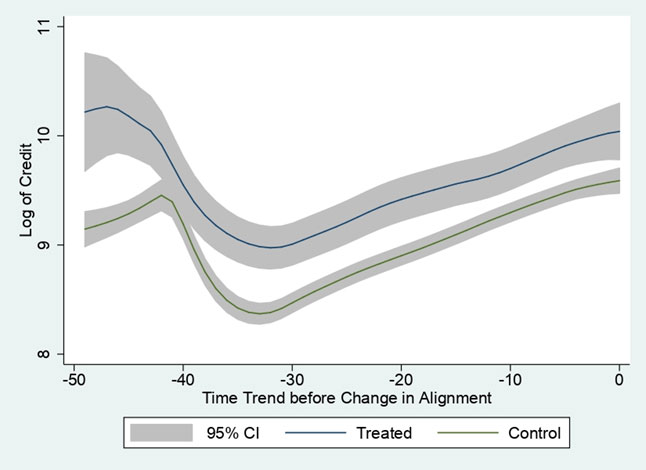

Although, lead bank of a district does not change, change in alignment may occur on account of reasons such as change in convenorship of the state (for example, from Union Bank of India to State Bank of India (SBI) in Manipur in 2005, and Allahabad Bank to Bank of India in Jharkhand in 2013), formation of a new state (for example, Telangana1 in 2014), or merger of a bank and its associates (for example, SBI in 2017). Could the change in alignment of a district be driven by credit disbursement, instead of alignment affecting credit, as posited here? In Figure 1, I plot the trend of (log of) credit in the quarters leading up to the change in alignment for districts that exhibit a change in alignment (‘treated’) and neighbouring districts that do not (‘control’) experience any change in alignment. The pre-trends appear to be parallel, indicating the absence of any unusual change in credit disbursement that could influence the choice of lead and convenor banks.

Figure 1. Time trend of credit disbursement (up to change in alignment) of districts that experience change in alignment, and neighbouring districts that do not experience change in alignment

Note: A 95% confidence interval (CI) is a way of expressing uncertainty about estimated effects. Specifically, it means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

Impact of negative income shock on long-term savings: Aligned vs. non-aligned districts

Next, I observe the impact of a negative income shock on long-term savings. Specifically, if aligned districts do have lower bottlenecks to access credit, then the ability to borrow easily should ameliorate the impact of an exogenous (external) economic downturn on long-term savings (Eswaran and Kotwal 1990).

I use scanty monsoon (20% below normal) in a district as proxy for a negative income shock, and quarterly term deposits2 as a measure of long-term savings, for the period 2012-20163 After a scanty monsoon (third quarter of a financial year), aligned districts should have access to credit, which should prevent their long-term savings from getting depleted. Consistent with this hypothesis, term deposits in non-aligned districts are found to fall by 25% in the quarter after a scanty monsoon, but there is no such reduction in term deposits for aligned districts.

Could monsoon rainfall be correlated with unobservable district-level characteristics? If aligned districts are more susceptible to scanty monsoon rainfall, then households may be better prepared for consumption smoothening, which may bias the above result. A further statistical test of difference in district-wise departure of monsoon rainfall from normal levels, rules out this concern.

Conclusion and policy implications

In India’s Lead Bank scheme, each district is assigned a public-sector bank as lead bank to improve district-level financial inclusion, and each state is assigned a public-sector bank to monitor the lead banks. My study finds that when district- and state-level agents of this scheme belong to the same corporate entity, credit disbursement is 21% higher. The results are explained by lower cost of monitoring of the state-level agent, which induces higher effort by district-level managers.

Whether greater credit disbursement is good or bad from a social welfare perspective is a separate matter. This requires assessing ‘adverse selection’4 or ‘moral hazard’5 in allocating credit at the district level. To do so, one would need data on district-level non-performing assets (NPAs), which to my knowledge, is currently unavailable in the public domain.

This limitation notwithstanding, the results shed light on how organisational design may influence organisational performance. Complex organisational set-ups operate in the various welfare schemes in India, such as distribution of subsidised fertilisers, LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) distribution, Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (crop insurance scheme), UDAN (regional aviation connectivity scheme), and so on. Implications from theories of organisational economics may help understand and address distortions, and ultimately, improve public service delivery.

Notes:

- The state of Andhra Pradesh was bifurcated to form two states – Telangana and the residual region of Andhra Pradesh – in 2014.

- District-wise monsoon rainfall was available only for 2012-2016.

- Term deposits are long-term saving instruments, which offer high, risk-free returns.

- Adverse selection occurs when buyers and sellers in a market have unequal information, and this can distort the usual market process and lead to market failure.

- Moral hazard is a situation in which one party gets involved in a risky event knowing that it is protected against the risk and the other party will incur the cost. It arises when both the parties have incomplete information about each other.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Further Reading

- Acharya, VV and N Kulkarni (2019), ‘Government Guarantees and Bank Vulnerability during a Crisis: Evidence from an Emerging Market’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper w26564.

- Eswaran, Mukesh and Ashok Kotwal (1990), “Implications of credit constraints for risk behaviour in less developed economies”, Oxford Economic Papers, 42(2):473-482.

- Gupta, S (2020), ‘Career Concerns and Distortions in Credit Uptake: Evidence from India’s Lead Bank Scheme’, Working Paper.

- Holmström, Bengt (1999), “Managerial incentive problems: A dynamic perspective”, The Review of Economic Studies, 66(1):169-182.

- Williamson, Oliver E (1981), “The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach”, American Journal of Sociology, 87(3):548-577.

26 October, 2020

26 October, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.