India's carbon emissions in 2014 were more than three times its level in 1990. While the emissions have increased sharply, their distribution across income groups is extremely skewed. The poor in India who contribute the least to climate change face the maximum brunt. In this post, Azad and Chakraborty discuss a proposal of taxing carbon while redistributing the revenue to the poor by giving them access to free energy up to a limit.

Climate scientists have pressed the panic button. They are warning that time is running out as the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report suggests that we, as humankind, might have just over a decade left to limit global warming. However, this is only possible if there are rapid, far-reaching, and unprecedented changes in all aspects of our lifestyles, especially those of the affluent in our society. And that is because as the IPCC shows, there is more than a 95% probability that human activities are responsible for warming the planet and, thereby, the climate change. A recent study shows that if immediate actions are not taken, the Earth will permanently change into a ‘Hothouse Earth’, after which any efforts made to reverse this global phenomenon will prove futile because that threshold limit might have been crossed (Steffen et al. 2018). In order to stabilise the temperature to no or limited overshoot of 1.5 degree Celsius, total global emissions will need to fall by 45% by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050. Despite such dire predictions, both the global North and the South, albeit to varying degrees and for different reasons, are behaving like ostriches. The North blames the South claiming that the sharp rise in carbon emissions today is originating in the newly industrialising countries and they should cut it down whereas the South says the North has done it in the past so, it is their turn to cut emissions now. In this bogey tug of war, it is the ordinary citizens – particularly the poor of the world – who are at the receiving end, as a result of environment-induced dramatic changes in the livelihood and habitats of tropical regions.

This passing the buck is not going to help. Instead, there is a need for collective and coordinated global action which will also simultaneously cater to their narrowly defined ‘national’ interests. When it comes to mitigation, there’s absolutely no doubt the global North has to shoulder a higher burden of adjustment both because of their past and current contributions as well as their greater access to funds. At the same time, it is also true that the global South too has to carry a share of this burden. After all, it is the global South, which is going to face the wrath of climate change at disproportionately higher levels because of its tropical location with already high temperatures and high density of population. Our argument here is restricted to how the global South needs to respond to this challenge, with India as a case in point, since India’s battle to tackle climate change could determine the world’s fate.

Inequality in India’s carbon emissions

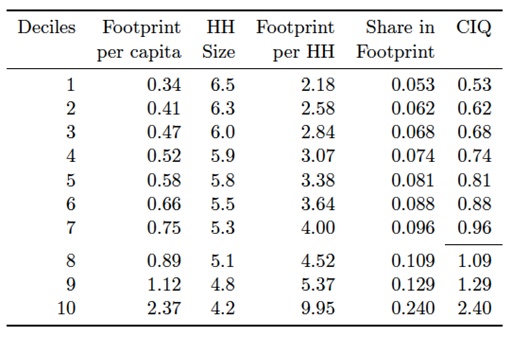

Greenhouse gas emissions – especially carbon emissions – are at the heart of the problem of climate change. In 2014, India's total carbon emissions were more than three times the levels in 1990 (see Figure 1). This is so because of India’s heavy dependence on fossil fuels, and a dramatically low level of energy efficiency.

Figure 1. CO2 emissions in India (in kilotonnes)

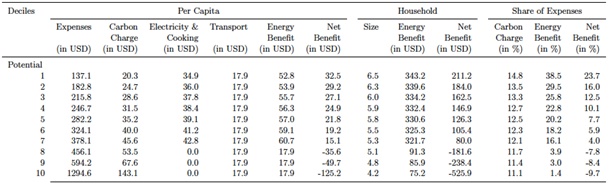

While the emissions have increased sharply, its distribution across income groups is extremely skewed (Sharma 2011). If one calculates the carbon footprint of households across income deciles (Table 1), the footprint of the richest 10% (as per the latest National Sample Survey (NSS) 68th Round data in 2011-12) comes out to be seven times as high as that of the poorest! Climate injustice quotient (CIQ) in Table 1 measures the carbon footprint of a decile as a proportion of their share in the population, and shows that the extent of inequality is quite stark. The bottom 70% of the Indian population contributes lesser carbon emissions than their share in the population.

Table 1. Inequality in carbon emissions

Source: Authors’ calculations based on NSS 2011-12 (68th round) - Schedule 1.0 (Type 1) - Consumer Expenditure and Input-Output tables from World Input-Output Database.

Notes: HH stands for households and CIQ stands for Climate Injustice Quotient.

What this essentially means is that it is the poor in India who contribue the least to the climate change problem and might, paradoxically, face the maximum brunt of it! Any environmental policy, therefore, has to be one which, apart from addressing the root cause, squarely addresses this paradox. It is important from the point of view of justice as well as acceptance by the broader sections of the people.

The question is how?

The need for a carbon tax and ‘Right to Energy’ programme

Emissions can be curbed when people are persuaded to move away from fossil fuels and adopt greener forms of energy and when there is improvement in energy efficiency (Pollin and Chakraborty 2015). But how do we achieve that? By taxing carbon, period. If the revenue thus generated is used for a systematic overhaul of the energy mix in the economy, then carbon taxes address both the demand (increasing prices of carbon-intensive products) and the supply side of carbon emissions.

The problem, however, is that carbon tax, much like any other indirect tax on a necessary good, puts a more substantial burden on the poor than on the rich because the poor consume a higher share of their income. Such a carbon tax will therefore perpetuate income inequality, let alone addressing the issue of climate injustice. Is there a way out?

In the North, a case has been made out to distribute the carbon revenue equally among the citizens that will invert the regressive incidence of these taxes (Boyce 2018). Unlike the North, it has generally been found, especially in the context of developing countries, that cash transfers need not have the redistributive impact that is intended on paper because of people’s limited access to banking, lack of control over finances by women in the households, lack of inflation indexation, etc.

Our policy proposal is that instead of cash, a part of the carbon revenue is spent on a ‘Right to Energy’ programme. According to this programme, all households will have access to free electricity and transport (the two most carbon-intensive consumption categories) up to a certain limit. Since for the eighth decile onwards (Table 1), carbon footprints far surpass their share in the population, we take the median consumption of both these commodities in the seventh decile to set this limit. This is the justice component of our policy which is comparable to the climate injustice faced by these sections of the population. So, instead of a carbon tax dividend, all citizens of the country will have an entitlement to a dividend in the form of free energy up to a limit.

As of 2016, around 20% of India's population did not have access to electricity. In July 2012, India experienced a blackout affecting roughly 700 million people. Through this Right to Energy programme, every household in India will have access to electricity, a feat that almost all the governments since independence have dreamt of but failed to deliver. The free entitlement of fuel and electricity for a household comes out to be 189 kWh (kilowatt hour) per month based on our calculations from the NSS data. Anything above this limit will be charged in full to control misuse of this policy. Travel passes with pre-loaded balance amount of Rs. 70 per person per month, which can be used on any mode of public transport, private and government alike, will be available for every citizen to avail.

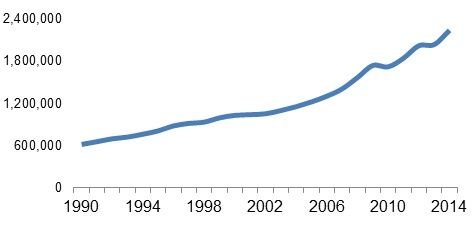

Table 2 shows how climate injustice (Table 1) is inverted through this policy. It is not surprising that the carbon charge as a share of expenses declines as we move up the income ladder, that is, the carbon tax is regressive. But the benefit of free electricity and transport (up to a certain limit) under this Right to Energy programme more than compensates for the carbon charge levied on the poorer households. And not surprisingly, the pyramid of injustice is inverted as can be seen from declining net benefit with rising income.

Table 2. Right to energy: A progressive alternative

Source: Authors’ calculations based on NSS 2011-12 (68th round) - Schedule 1.0 (Type 1) - Consumer Expenditure and Input-Output tables from World Input-Output Database.

There are additional reasons why this programme will be more successful than carbon dividends. One, it has the effect of enticing the poor to move away from traditional forms of energy consumption because the price of energy will be zero for them as compared to a positive shadow price, which they spend in terms of time used for collection of wood/cow dung cakes, etc. As opposed to this, a cash transfer in all likelihood will not have the same effect since these other forms of energy consumption will still be available to them free of cost. Two, availability of free energy (up to a limit) addresses the issue of stealing of electricity for consumption since there will be no incentive left for those illegally accessing it at the moment.

The remaining part of the carbon revenue generated from carbon taxes can be used for a clean green energy programme, which addresses the problem of environmental degradation from the production side. Indian economy’s energy mix needs to be improved through investment in clean renewables, including solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and low-emissions bioenergy, and among fossil fuel energy sources, by increasing the proportion of natural gas consumption relative to coal. The energy efficiency also needs to be raised through investments in improving industrial energy efficiency, building retrofits and smart grids, and expansion of public transports. Our estimates show that this clean green energy programme requires an additional 1.5% of GDP (gross domestic product) annually (over and above the current level of 0.6% being spent annually) over the next two decades (Pollin and Chakraborty 2015). If done, it will bring the emissions down by half from the currently projected levels. Moreover, since this expenditure is financed by the carbon tax revenue, it will be a revenue-neutral policy with no implications on the fiscal deficit. The level of carbon tax required for this policy to come into effect is Rs. 2,818 per metric tonne of carbon dioxide. It will be levied upstream, that is, at the ports, mine-heads, etc. While almost all the commodities’ prices will rise as a result of that, the highest rise will be in fuel and energy since the carbon content is the highest in this category. To give an idea about the pinch that will be felt, the average price of electricity will rise from its current value of Rs. 3.73 to Rs. 4.67 per kWh.

This policy not only curbs emissions but also delivers on providing more employment since the employment elasticity in greener forms of energy is higher than those in fossil fuel based energy (United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and Global Green Growth Initiative (GGRI), 2015). Higher prices of commodities according to their carbon content will induce households, including the rich, to look for substitutes in green energy. It is difficult to put a figure on health benefits that such a policy will entail, but as a rough measure, a significant part of more than 3 % percent of India’s GDP currently spent on pollution-induced diseases will inevitably come down.

This proposal simultaneously addresses the issue of equity and climate change. As a result of this policy – taxing all while redistributing the revenue in kind to the poor – those who pollute more (elite) because of their lifestyle choices will indirectly be paying for the energy usage of those who pollute less. One could think of it as a 'Robin Hood' tax!

Further Reading

- Boyce, James K (2018), “Carbon Pricing: Effectiveness and Equity”, Ecological Economics, 150: 52-61. Available here.

- Bradford, Colin I and Ramesh Thakur (2007), ‘Climate Change and Global Leadership’, Brookings op-ed, 10 February 2007.

- Ghani, E, A Grover and W Kerr (2015), ‘India’s chaotic and messy use of energy’, Let’s Talk Development, The World Bank.

- Pollin, Robert and Shouvik Chakraborty (2015), “An Egalitarian Green Growth Programme for India”, Economic & Political Weekly, 50(42).

- Pollin, R and S Chakraborty (2015), ‘An Egalitarian Green Growth Programme for India’, Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), Working paper.

- Sharma, Shankar (2011), “Hiding Behind the Poor”, Frontier, 43(28): 23-29, January 2011.

- Steffen, Will, Johan Rockström, Katherine Richardson, Timothy M Lenton, Carl Folke, Diana Liverman, Colin P Summerhayes, Anthony D Barnosky, Sarah E Cornell, Michel Crucifix, Jonathan F Donges, Ingo Fetzer, Steven J Lade, Marten Scheffer, Ricarda Winkelmann and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber (2018), “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(33): 8252-8259.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2010), ‘Fact sheet: The need for strong global action on climate change’, November 2010.

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and Global Green Growth Initiative (GGRI) (2015), ‘Global Green Growth: Clean Energy Industry Investments and Expanding Job Opportunities’, Volume I: Overall Findings, Vienna and Seoul.

22 April, 2019

22 April, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.