In an attempt to address Delhi’s grave pollution problem, the state government experimented with a driving restrictions policy for a fortnight in January. Based on a phone survey of a sample of 614 drivers in the city, this column describes how the policy changed drivers’ behaviour in terms of labour supply,

Many large cities in developing countries suffer from severe traffic congestion and high pollution levels. Together, these issues are likely to have considerable and varied negative consequences on human health and economic activity. Indian cities are particularly affected, with six out of the top 10 most polluted cities in the world being from India (World Health Organization (WHO), 2014).

While pollution has many causes, traffic congestion is a particularly salient contributor, and several cities worldwide have adopted driving restrictions as a policy to ration road space and bring down pollution levels. Prodded by the Delhi High Court, the Delhi government recently joined this

Potential benefits and costs of driving restrictions

The potential benefits of driving restrictions have been studied and debated extensively, both for the Delhi trial period and for similar policies worldwide. The early consensus was that these policies did not lead to any change in aggregate pollution levels, and researchers argued this was due to drivers purchasing additional and potentially more polluting vehicles (Eskeland and Feyzioglu 1997, Davis 2008, de Grange and Troncoso 2011, Bonilla 2013, Gallego et al. 2013). However, more recent studies find that driving restrictions in Quito and Beijing reduced congestion and pollution (Carrillo et al. 2015, Viard and Fu 2015). A study of Delhi’s odd-even policy that compares data across time within Delhi and just outside Delhi also finds that the policy was effective in reducing peak pollution levels (Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC India), 2016).

Meanwhile, the policy’s potential costs also deserve close

Impact on drivers’ behaviour

The study enrolled 614 car drivers3 who came under the purview of the driving restrictions in

The results below describe how the policy changed drivers’ behaviour between restricted and unrestricted days, in terms of labour supply, number of daily trips, travel modes, and satisfaction. It is thus important to keep in mind that these results do not describe how drivers’ behaviour changes during the policy relative to before the policy; rather they capture the day-to-day variation in outcomes while the policy was in effect. This information complements and is complemented by existing studies of the aggregate impact of the policy.

The policy led to a substantial and significant decrease in the use of primary cars on restricted days, as intended and as expected. At the same time, there was also a small yet significant non-compliance with the policy. On a typical unrestricted day, that is, a day when the respondent is allowed to drive their primary car, 50% of respondents travelled using their primary car4. This simply means that even in our sample of regular drivers, some people do not make any trips on some days, while others use alternative travel modes, even if they are allowed to use their car. The fraction of respondents who travel using their primary car drops to 17% on restricted days, a two-thirds decrease. However, this means that 17% of respondents reported driving on days when their vehicle was restricted, that is, they most likely did not respect the rule, or travelled before 8 am when the policy enters into effect5.

It is unlikely that the non-compliance finding is spurious. Respondents who misreport are likely to underestimate non-compliance – an illicit behaviour – rather than overestimate it. The fraction of drivers travelling before 8 am – when the odd-even policy comes into effect – is 3.5% on restricted days, which means around 14% of drivers were actually non-compliant. Taking sampling uncertainty into account, non-compliance is above 10% with high confidence. Meanwhile, only three respondents in the entire study ever reported paying the Rs. 2,000 fine.

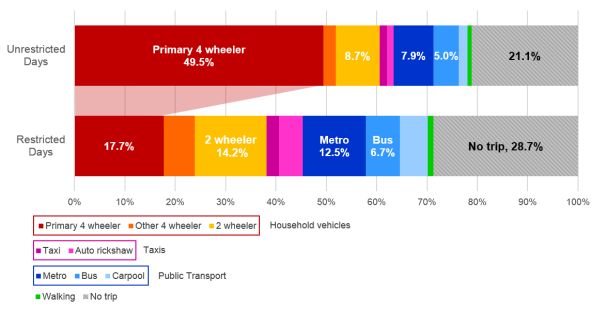

The 32% of drivers who switched away from their primary car on restricted days chose from a diverse range of alternatives, depicted in Figure 1. Indeed, all travel-mode categories other than primary four-wheelers saw increases, most of which were statistically significant. First, the large reduction in primary car usage was attenuated by an increase in other (unrestricted) household vehicles, from 2.6% to 6.4%, and an increase in two-wheelers, from 9.0% to 15.1%. Note that these are short-term changes, and in the medium and

Restricted days witnessed a significant shift to public transportation, with approximately 5% more drivers turning to metro, and 4% more to carpooling. The shift towards using the bus is also positive; however, it is smaller and not statistically significant. In the entire study sample, there were no reports of drivers using bicycles to commute, and walking was chosen by a very small fraction of respondents both on restricted and on unrestricted days.

Figure 1. Impact of the odd-even policy on daily travel modes

Figure 1 also reveals that some drivers simply find it too inconvenient to travel if their primary

Overwhelmingly, Delhi drivers report being satisfied with their daily commute. Indeed, 90% of drivers who made a trip on an unrestricted day say they were satisfied with the trip. The satisfaction rate is lower on restricted days, yet at 83% it is still very high. The results on inconveniences follow the same pattern: we detect an increase in reports of inconveniences, from 11% on unrestricted days to 15% on restricted days, which is mostly accounted for by increases in reports related to late arrivals and trip timing. However, we are not able to detect any changes in actual (self-reported) trip duration, departure time or distance. This may be related to imprecise answers from respondents, who very often ‘round-off’ these values to the nearest 15 minutes or 5 kilometres. Importantly, we do not find any evidence of reports of getting lost or stranded, being harassed during the commute, or feeling tired after the commute.

What this means

In the press, the odd-even policy

A significant share of drivers – very likely at least 10% – did not comply with the policy. These drivers may have chosen to break the rule either because the inconvenience of switching to another transport mode was too high, or because they thought that enforcement was sufficiently unlikely. Both issues should be of concern for policymakers, yet the policy responses differ. Unfortunately, it is not possible to credibly distinguish between the two hypotheses with available data.

The results highlight the great diversity of alternatives available to drivers. There does not exist any main alternative to car driving; instead, drivers are remarkably evenly divided between using other household vehicles, taxis, public transport options, and travelling less. In particular, this implies that the effect of the policy on the use of any kind of private or hired motorised vehicle is significantly smaller than the effect on primary four-wheelers, and the switch to public transport is less than one might expect.

In many ways, the debate around the effects of the odd-even policy highlights the need for more rigorous and carefully designed studies, in addition to smart policy experiments and quality data, to uncover which policies work most effectively to contain congestion and pollution. This

Notes:

- The full list of exemptions can be found here.

- For instance, Viard and Fu (2015) show evidence that the driving restrictions in Beijing increased leisure and reduced labour supply of workers with flexible hours.

- The sample was male drivers, owners and regular users of a petrol or diesel car.

- The travel mode numbers are slightly smaller than those quoted in the paper. For Figure 1, we categorise each respondent as using exactly one (main) travel mode, while in the survey respondents could select multiple options. In order of priority, the options were: if the respondent used a primary four-wheeler, other four-wheeler owned by

household , two-wheeler, taxi, auto rickshaw, carpool, metro, bus, walking, and no trip. - Respondents to the phone survey were asked about same-day trips, so no trips after 8 pm were recorded. None of the car trips on restricted days was for

emergency purpose.

Further Reading

- Bonilla Londoño, JA (2013), ‘Essays on the Economics of Air Quality Control’, Economic Studies 213, Department of Economics, University of Gothenburg.

- Carrillo, Paul E, Arun S Malik and Yisen Yoo (2014), “Driving Restrictions That Work? Quito´s Pico y Placa Program”, Canadian Journal of Economics, Forthcoming. Available at: https://www.gwu.edu/~iiep/assets/docs/papers/Carrillo_Malik_Yoo_IIEP2013-01.pdf

- Davis, Lucas W (2008), “The Effect of Driving Restrictions on Air Quality in Mexico City”, Journal of Political Economy, 116(1), 38-81. Available at: http://instructional1.calstatela.edu/mfinney/courses/433/articles/mexico_program.pdf

- Energy Policy Institute at University Chicago (EPIC India) (2016), ‘Odd-Even Program: Analysis Q&A’.

- Eskeland, Gunnar S and Tarhan Feyzioglu (1997), “Rationing can backfire: The Day without a Car” in Mexico City”, The World Bank Economic Review, 11(3): 383-408.

- Gallego, Francisco, Juan-Pablo Montero and Christian Salas (2013), “The effect of transport policies on car use: Evidence from Latin American cities”, Journal of Public Economics, 107: 47-62. Available at: http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic788896.files/Montero_Paper.pdf

- Grange de, Louis and Rodrigo Troncoso (2011), “Impacts of vehicle restrictions on urban transport flows: The case of Santiago, Chile”, Transport Policy, 18(6): 862-869.

- Viard, Brian V and Shihe Fu (2015), “The effect of Beijing´s driving restrictions on pollution and economic activity”, Journal of Public Economics, 125: 98-115.

08 February, 2016

08 February, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.