India was among the hardest hit by the Fed’s ‘taper talks’. This column argues that this impact was large for two reasons. First, India received huge capital flows before. This had made it a convenient target for investors seeking to rebalance away from emerging markets. Second, macroeconomic conditions had worsened, which rendered the economy vulnerable. The measures adopted in response were ineffective in stabilising the financial markets. Implementing a medium-term framework that limits vulnerabilities and restricts spillovers could be more successful.

On 22 May 2013, Chairman Ben Bernanke first spoke of the possibility of the Fed tapering its security purchases1. This and subsequent statements, collectively known as ‘tapering talk’, had a sharp negative impact on the emerging markets (Aizenman et al. 2014). India was among those hardest hit. Between 22 May 2013 and the end of August 2013, the rupee exchange rate depreciated, bond spreads2 increased, and stock markets declined sharply. The reaction was sufficiently pronounced for the press to warn that India might be heading toward a full-blown crisis that requires an emerging market to seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Why was India impacted so severely?

The impact was large for two reasons.

- First, India’s large and liquid financial markets had received significant volume of capital flows in prior years, making it a convenient target for investors seeking to rebalance away from emerging markets; and

- Second, its macroeconomic vulnerabilities had increased in the years prior to the tapering talk, making it susceptible to capital outflows and limiting the policy room to address the shock that the tapering talk initiated.

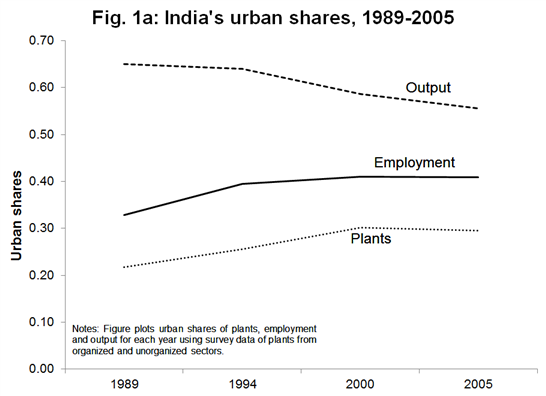

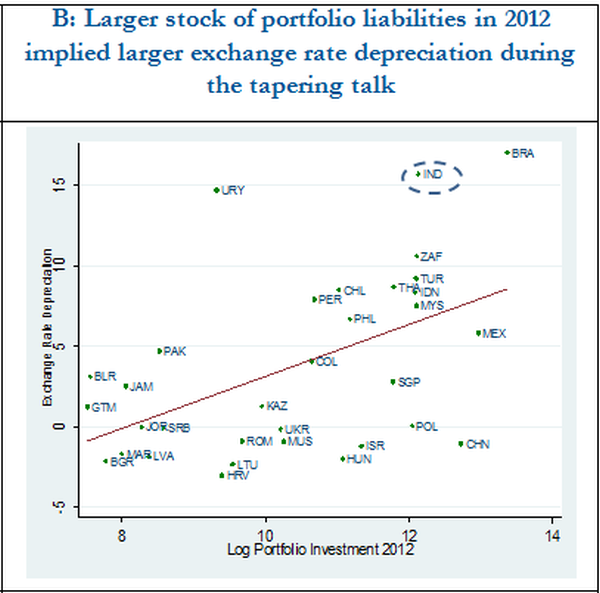

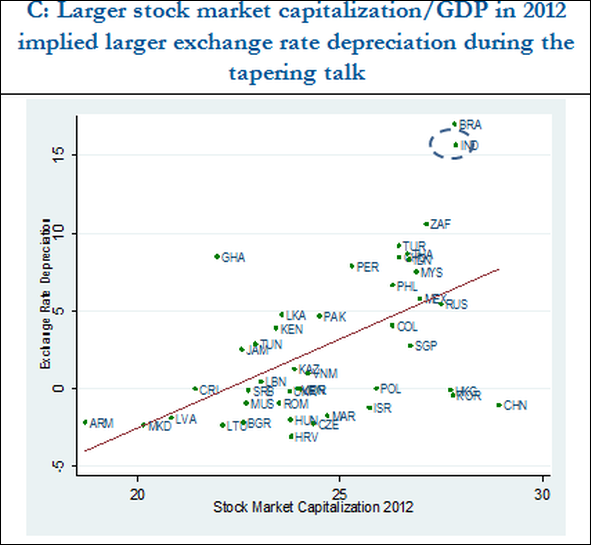

In a recent paper, two of us analyse the impact of the Fed’s tapering talk on exchange rates, foreign reserves, and equity prices between May 2013 and August 2013 (Eichengreen and Gupta 2014). We find that an important determinant of the impact was the volume of capital inflows countries received in prior years and the size of their local financial markets. Those which received larger inflows of capital and which had larger and liquid markets experienced more pressure on their exchange rate, reserves, and equity prices once the tapering talk began. Evidently, investors are better able to rebalance their portfolios away from such countries. India ranks high in terms of the size and liquidity of its financial markets and the extent of capital flows it received in prior years, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Size and liquidity of financial markets and effect on the exchange rate during Fed’s tapering talk (India was among the largest and most liquid markets)

Figure 1b. Size and liquidity of financial markets and effect on the exchange rate during Fed’s tapering talk (India was among the largest and most liquid markets)

Figure 1c. Size and liquidity of financial markets and effect on the exchange rate during Fed’s tapering talk (India was among the largest and most liquid markets)

Figure 1d. Size and liquidity of financial markets and effect on the exchange rate during Fed’s tapering talk (India was among the largest and most liquid markets)

Source: Eichengreen and Gupta (2014)

Source: Eichengreen and Gupta (2014)Note: Stock market capitalisation refers to the total currency value of the all the outstanding shares of a publically-traded company.

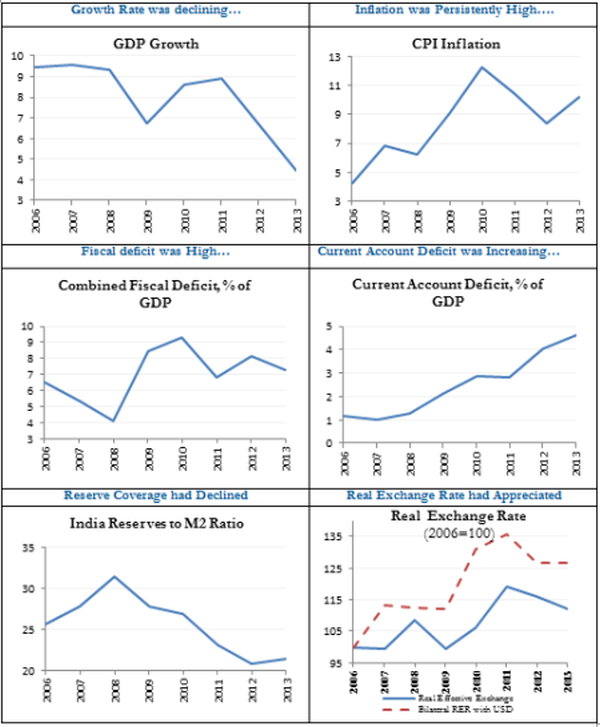

In addition, emerging markets that had allowed their real exchange rates to appreciate and the current-account deficits to widen during the period of quantitative easing, saw larger impact. Similar vulnerabilities had built in India in prior years. Its current-account deficit had increased from about 1% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2006 to nearly 5% in 2013; and its real exchange rate had appreciated markedly (Figure 2). Its fiscal deficit had increased, and inflation at about 10% was proving to be stubbornly high. These macroeconomic weaknesses had surfaced in the midst of a sharp growth slowdown. Although the level of foreign reserves was considered comfortable by some metrics, the effective coverage they provided had declined unmistakably since 2008.

The specific factors contributing to high fiscal or current-account deficit also indicated increased economic and financial vulnerabilities. The increase in budget deficit was due to an increase in current expenditure (in response to the Global Crisis of 2008, the headwinds of which were palpable in India by early 2009), than to a pickup in public investment. The increase in current-account deficit, largely a mirror effect of increased current expenditure, was characterised by some deflection of private savings into the import of gold. It reflected a dearth of attractive domestic outlets for personal savings in a high inflation environment, where real returns on many domestic financial investments had turned negative. Loose monetary policy in advanced countries meanwhile made those deficits easy to finance, further relieving the pressure to compress them.

Figure 2. Macroeconomic imbalances were evident in the Indian economy prior to the period of tapering talk

Sources: GDP: Central Statistical Organisation (CSO); Consume Price Index (CPI) Inflation: Citi Research; Gross Fiscal Deficit, Current-Account Deficit: Reserve Bank of India (RBI); Reserves to M2 Ratio, International Financial Statistics (IFS); Real Effective Exchange Rate (CPI based, six currency): RBI; Bilateral Real Exchange Rate (RER) calculated using data from IFS. Years refer to fiscal years.

Sources: GDP: Central Statistical Organisation (CSO); Consume Price Index (CPI) Inflation: Citi Research; Gross Fiscal Deficit, Current-Account Deficit: Reserve Bank of India (RBI); Reserves to M2 Ratio, International Financial Statistics (IFS); Real Effective Exchange Rate (CPI based, six currency): RBI; Bilateral Real Exchange Rate (RER) calculated using data from IFS. Years refer to fiscal years.Note: M2 is a measure of money supply that includes cash and checking deposits (M1) as well as savings deposits and other time deposits, which are less liquid but can be quickly converted into cash or checking deposits.

The policy response

In response, the Indian authorities intervened in the foreign exchange market. They increased the overnight lending rate3 (the marginal standing facility rate) by 200 basis points to 10.25%. Gold imports being partly responsible for a large current-account deficit, the import duty on gold was raised from 6 to 15%. They opened a separate swap window4 for three public sector oil marketing companies to reduce exchange rate volatility, and imposed new measures to restrict capital outflows from residents. The latter included reducing the limit on the amounts that the residents could repatriate or invest abroad5.

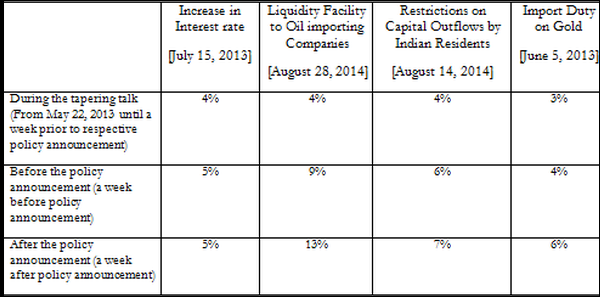

We analyse the impact of these measures by comparing the exchange rate five days after the announcement of the policy, with its value five days prior to the announcement. The results are summarised in Table 1 (shorter windows of 2 or 3 days yielded similar results).6

Table 1. Impact of policy announcements on exchange rate

(Estimated % depreciation during the tapering talk, and before and after the policy announcement, compared to the tranquil period)

As is evident from Table 1, these measures were largely ineffective in stabilising the exchange rate. In particular, the RBI’s efforts to restrict capital outflows from residents and Indian companies had decidedly mixed effects. In the five days from the time when the announcement was made, exchange rate depreciation accelerated, and portfolio equity flows and equity prices declined. Subsequently, on 4 September 2013, upon formally joining the RBI, the new governor Raghuram Rajan issued a statement expressing confidence in the economy and highlighting the Bank’s comfortable foreign reserves position. In addition, he announced new measures to attract capital through deposits targeted at the Indian diaspora and relaxed partially the restrictions on outward investment that had been introduced previously. These new announcements and further guidance from the Federal Reserve Board, indicating more nuanced view of the tapering, helped calm the markets.

The way forward

India’s experience suggests that once a country is in the midst of a rebalancing episode, it can be difficult to counter the effects. It is better to put in place a medium-term policy framework that limits vulnerabilities, restricting the spillover impact in the first place, while maximising policy space.

Maintaining a sound fiscal balance, a sustainable current-account deficit, and an environment conducive to investment are integral to such a framework. Less obvious elements include managing capital flows to encourage relatively stable longer-term flows while discouraging volatile short-term flows, avoiding excessive appreciation of exchange rate through interventions using reserves and macroprudential policy, holding a larger stock of reserves, where feasible signing swap lines with other central banks, and preparing the banks and the corporates to handle greater exchange rate volatility. Finally, while implementing the medium-term framework and adopting any emergency crisis-management measures, countries need to adopt a clear communication strategy to interact smoothly and transparently with the market participants.

This column first appeared on VoxEU.

Notes:

- Following the financial crisis, the US Federal Reserve began a bond-buying programme in 2008 in order to pump money into the financial system. This is known as Quantitative Easing (QE).

- Bond spread refers to the difference between the yields of two bonds with differing credit ratings. Typically, a corporate bond with a certain amount of risk is compared to a standard risk-free government bond. The bond spread is the additional yield that could be earned from a bond which has a higher risk.

- Overnight lending rate refers to the rate that large banks use to borrow and lend from one another; the principal and interest is to be returned at the start of the next business day. The central bank may also participate in the overnight lending market.

- A swap window is one that involves the exchange of principal and interest in one currency for the same in another currency. Say, an Indian company needs to acquire US dollars and a US company needs to acquire Indian Rupees. The two companies could arrange to swap currencies by establishing an interest rate, an agreed upon amount and a common maturity date for the exchange.

- None of these policy measures were novel in the Indian context, having been implemented at different instances in the past, for example, import duty on gold was prevalent until the early 1990s; deposits from the Indian diaspora were attracted in a similar fashion twice in the past, in 1998 and in 2000; and a separate swap window was made available to the oil importing companies in 2008 to reduce volatility in the foreign exchange market after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

- See Basu et al. (2014) for details, as well as for results on the impact of policy announcements on equity prices, portfolio debt, and portfolio equity flows.

Further Reading

- Aizenman J, M Binici and M Hutchinson (2014), ‘The transmission of Federal Reserve tapering news to emerging financial markets’, VoxEU, 4 April 2014.

- Basu, K, B Eichengreen, and P Gupta (2014), ‘From Tapering to Tightening: The Impact of the Fed’s Exit on India’, Policy Research Working Paper, WPS7071, World Bank.

- Eichengreen, B and P Gupta (2014), ‘Tapering talk: The Impact of Expectations of Reduced Federal Reserve Security Purchases on Emerging Markets’, Policy Research Working Paper, WPS6754, World Bank.

27 November, 2014

27 November, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.