It is widely believed that skill gaps are constraining Indian manufacturing, and closing these gaps has become a national priority. This column argues that the public debate on India’s skill gaps rests on weak conceptual foundations. While some industries do suffer from real skill gaps, others are constrained by commercial difficulties that may be better addressed through policies other than skill development programmes.

Much has been made of India’s skill gaps. The government and some industry leaders have determined that Indian workers’ alleged lack of skills is a critical constraint on manufacturing growth and job creation. Closing these gaps has become a national priority, leading to significant public spending (often implemented through public-private partnerships), interest in curricular reforms, conferences and studies on skill gaps, and the formation of new public agencies such as the National Skills Development Corporation (NSDC, various years; Chenoy 2012). Yet, this position contrasts with the results of employer surveys, which consistently rank corruption, infrastructure deficits, tax rates, practices of the informal sector, access to finance and land, and labour regulations, as more serious business environment constraints than inadequate worker education (World Bank, 2014).1 The position also contradicts the experiences of young workers, whose unemployment rates rise with their education level (Labor Bureau, 2013).

Analysing skill gaps in Indian manufacturing

As part of a World Bank-funded interdisciplinary study of constraints on job creation in India, my collaborators at ICRIER (Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations) and I are currently conducting a study of skill gaps amongst Indian manufacturing production workers. A firm hired by ICRIER is currently surveying representatives of 500 randomly selected organised-sector firms from five states (Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh) and five manufacturing industries (automobiles and parts, electronics, food processing, leather goods, and textiles). The survey began in September 2014, and results are expected around September 2015. In the meantime, Deboshree Ghosh, Arpita Patnaik (both at ICRIER) and I have visited seven factories, held discussions with multiple employers, managers, trainers and consultants involved in skill development projects, and read all the central government- and industry-sponsored reports on skill development that we could find.2

The people we have spoken with were not randomly selected, and we look forward to verifying our findings with survey data. Nevertheless, the qualitative data we have collected highlights consistent and serious problems with the conceptual definitions that seem to underpin public discussions on skill gaps in India. In this column, I discuss these problems in the hope of laying the foundation for more meaningful public discussions of the issue. I explain how a skill gap should be defined and contrast this definition with the one that is frequently applied by employers and appears to underpin industry and government reports. I also show how these conceptual differences make it difficult to interpret the signals emanating from skills’ markets.

Defining skill gaps: Economic vs. commercial

Economists and employers define skill gaps differently. Economists note that it is efficient for a worker to acquire a production skill if - and only if - the benefits to society (including workers, employers and taxpayers) of him/ her doing so exceed the costs to society of the worker acquiring the skill. The benefits primarily take the form of higher productivity at work, some of which may be shared with workers in the form of higher wages. The costs, which are borne in varying proportions by workers, employers and trainers, include the value of worker time spent on training (measured in foregone wages) and the direct costs of the skill training (including instructor time, materials, training infrastructure, and business losses due to mistakes by trainees). An economic skill gap is a situation in which efficient opportunities to invest in skills are not seized. An economic approach to skill development policy would therefore begin by assessing the benefits and costs of expanding the supplies of particular skills; a skill gap would be established if there is a failure to invest in skills for which these overall benefits exceed the overall costs. This would then trigger policy intervention to encourage workers, trainers and employers to work on filling these gaps.

Unfortunately, most of the reports generated by industry or the public sector that we have found do not assess the productivity benefits of skill acquisition to employers. Nor do they study the wage benefits of skill acquisition to workers, or the costs of skill acquisition. Instead, these reports offer lists of tasks that employers report that workers need to be able to perform better for production to proceed smoothly. The 2011 NSDC skill gap reports claim skill gaps against almost every single task in the manufacturing sector.3

What employers mean by “need” in this case is never defined. To an economist, only those skills that firms are willing to pay for are “needed”. Yet, our interviews indicate that employers have something quite different in mind. To them, what they are willing to pay is irrelevant. All that matters, given their often razor-thin margins, is what they can afford to pay. If they cannot find workers with the skills they want who are willing to work for them at the wages they can afford to pay, then they have a skill gap. Several employers have confirmed that this is their definition of a skill gap. We refer to this as a commercial skill gap. Unfortunately, it provides a poor basis for designing public policies on skill development.

Why economic, not commercial, definitions of skill gaps must guide policy

Designing effective skill development strategies that benefit both employers and workers requires cost-benefit analyses to identify skill gaps. Firms pay workers for their contribution to production. Therefore, if possessing a skill increases a worker’s productivity by less than what it costs to acquire the skill, the wage increases earned by those who acquire the skill will be insufficient to compensate them for the cost of acquiring it.

This is a real problem. Several trainers we spoke with identified some skills, such as cosmetology and garment-making, that trainees had come to regret investing in, because the jobs for which they trained either did not exist, were oversubscribed, or offered wages and working conditions that were too low to recover training costs. Survey evidence likewise corroborates the claim that not all vocational training is rewarded.4 Many employers at the September 2014 CII conference also acknowledged that students seem uninterested in vocational training, and CII has even organised a webinar on how to address (what they perceive as) students’ lack of motivation to fill skill gaps. The general indication is therefore that workers do not see sufficient benefits from acquiring some skills in which the government and industry claim there are skill gaps.

A further problem is that when all industrial sectors are deemed to suffer ‘skill gaps’, it is difficult to prioritise areas for policy attention. For example, in our field visits, we found evidence that improving pre-service vocational training would pass a cost-benefit test for plants making automotive parts (which involve a lot of expensive machinery and materials). Given the lack of pre-service training, automotive firms make extensive efforts to train workers during service, often offer them permanent employment to induce them to stay on, and pay much more than minimum wages. On the other hand, as part of a forthcoming study of the Indian garment sector with colleagues at the Asian Development Bank (ADB), all the employers we interviewed acknowledged that the skills of a typical sewing machine operator are acquired in only 2-6 weeks, and often on-site, at very little cost in wages, material and machine time. Moreover, employers in smaller garment firms often allow skilled workers to be poached rather than pay more than the minimum wage. While this evidence suggests that only the automotive firms behave as if skill gaps are costly, NSDC reports identify critical skill gaps in both industries.

A third problem is that, by treating commercial skill gaps as skill gaps at all, rather than simply as commercial problems, we prioritise skill development over other interventions that could do more to improve the competitiveness of Indian industries. To see this, note that a commercial skill gap is simply an indicator that margins in the industry are low: once an employer subtracts overheads, regulatory compliance costs, taxes, variable input costs (other than wages) and the cost of capital invested in the firm from their revenues, they have too little left over to pay skilled or easily trainable workers what they could earn in other industries. In other words, their problem is not a skills problem anymore than it is a tax, compliance or raw material cost problem. By lowering these other costs or helping firms to increase their revenues, government could enable them to offer higher wages, and so to hire more and better workers. What matters is whether skill development would generate more jobs per unit of public expenditure than these other interventions. For example, the ADB study shows that, in the garment sector, relieving bottlenecks in synthetic fabric supply chains would do much more to create garmenting jobs than would training garment workers.

Indeed, no employer that we interviewed felt that training additional workers would enable them to create more jobs. The constraints were usually somewhere else; inadequate demand for their product, difficulties in working with politically-connected labour unions and bottlenecks in upstream supply chains were common concerns, as was an unwillingness to take on significant debt in order to invest in more and better machinery and processes.

Supply or demand?

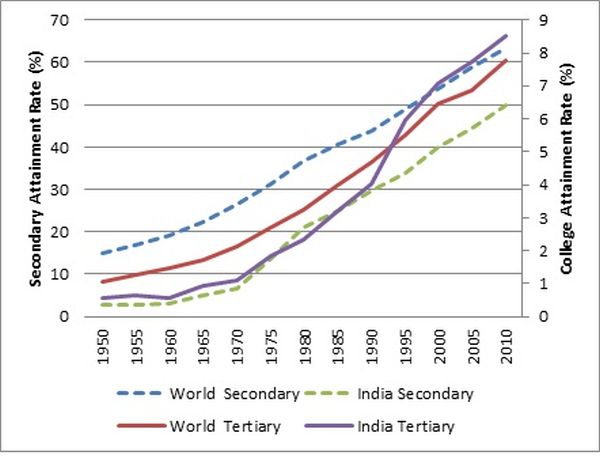

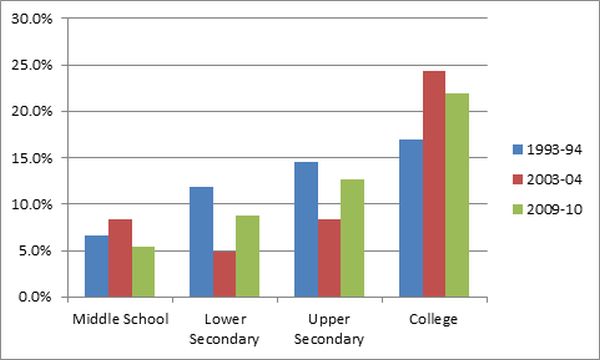

The skills-gap-everywhere narrative is also hard to reconcile with a basic supply and demand analysis. It emerges at a time when the supplies of secondary and college-educated workers, both in India and around the world, have grown enormously (Figure 1). Moreover, the wage-returns to secondary education have declined since 1993 (Figure 2). And finally, the NSDC’s original reports (2011) identify serious skill gaps in some relatively education-unintensive industries such as construction, textiles, garments, leather, and food-processing. Several employers and trainers have confirmed that workers with secondary education are easier to train than workers without secondary education. This being the case, it would be strange if there were a skills gap at a moment when trainable workers are becoming more available and at relatively cheaper rates, especially in industries that choose to hire some of the least trainable workers.

Figure 1. Education attainment for population aged 15 and above, 1950-2010

Figure 2. Wage returns to secondary and tertiary education levels, 1993-2010 (Workers with 5-9 years of labour-market experience)

The simplest explanation for these trends is that there are relatively few workers with industrial skills because demand for these skills is too low to justify the cost of investing in them – especially when general education opens up better paid job opportunities outside manufacturing. Indeed, following dramatic growth in educational attainment in recent years, employers routinely reported that workers now think they are “too good” for factory work.

Skill, or what?

So if some alleged skill gaps are really just reflections of firms operating on tight margins, why are employers talking about skill at all? Sometimes, it turns out, they aren’t. Several employers indicated that to them ‘attitude’ is a key component of skill. By attitude, they mean that workers should have a strong work ethic, be willing to make sacrifices for productivity (working night shifts, for example), and not be likely to add to the labour relations’ problems of firms. Two firms reporting highly cyclical demand actually indicated that a core ‘skill’ problem was how to have trained manpower when they needed it, and to not have to pay for it when they didn’t. In short, many concerns actually relate to labour relations and regulations, or simply the availability of manpower on demand, and fall outside the largely technocratic rubric of ‘skill development’.

Firms suffering economic skill gaps operate very differently from firms that are constrained by other factors, and they offer very different employment opportunities. For the benefit of workers and employers, it is imperative that we learn to tell them apart.

Notes:

- Education is not synonymous with skills. However, high quality education delivers foundational skills (literacy, numeracy, comprehension and reasoning) that are necessary for the successful acquisition of vocational and professional skills. More skill-intensive industries therefore require more educated workers.

- We also attended a September 2014 conference on higher education and skill development in Chandigarh organised by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and NSDC. This complements years of discussions with parents and students about career decisions, the factors that are considered, and their outcomes.

- NSDC is in the process of updating these reports. The more recent reports, prepared by KPMG, present a serious improvement on the 2011 reports, insofar as they acknowledge that low wage premiums for skilled workers are the most important disincentive for skill acquisition.

- According to my calculations from 2009-10 National Sample Survey (NSS) Schedule 10 data, 25% of workers in the labour force who received vocational training say that it was not helpful in finding a job or starting a business. Mehrotra (2014) reports that 34% of graduates of government-supported Industrial Training Institutes or the Apprenticeship Training Scheme reported that no jobs were available in their area of training.

Further Reading

- Asian Development Bank (forthcoming), ‘What constrains the growth of good jobs? The Case of Indian Apparel manufacturing’, Manila: The Philippines.

- Barro, RJ and JW Lee (2010), ‘A new data set of educational attainment in the World, 1950-2010’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15902.

- Chenoy, D (2013), ‘Public–Private Partnership to Meet the Skills Challenges in India’, in Maclean, R, S Jagannathan and J Sarvi (eds.), Skills Development for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth in Developing Asia-Pacific, Technical and Vocational Education and Training: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, Springer Netherlands, 19: 181-194.

- ET Bureau (2014), ‘Skill India is PM Modi´s dream project, there can´t be a crisis of budget: Sarbananda Sonowal’, The Economic Times, 28 September 2014.

- Government of India (2009), ‘National Skills Development Policy’.

- Indian Express (2014), ‘Full Text: Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speech on 68th Independence Day’, 16 August 2014.

- Labor Bureau (2013), ‘Report on youth employment unemployment scenario, 2012-13’, Ministry of Labour & Employment, Government of India.

- Mehrotra, S, A Gandhi, et al. (2013) ‘Estimating the Skill Gap on a Realistic Basis for 2013’, Occasional Paper, Institute for Applied Manpower Research.

- Mehrotra, S (2014), India´s Skill Challenge: Reforming Vocational Education and Training to Harness the Demographic Dividend, Oxford University Press.

- NSDC (various years), ‘Human Resource and Skill requirement reports’.

- World Bank (2014), ‘Enterprise Surveys: India’.

13 April, 2015

13 April, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.