While political interference is believed to be a major problem plaguing the electricity sector in India, there is little empirical evidence on the existence of political distortions or on their economic costs. This column demonstrates that Indian state governments increase the supply of electricity to constituencies that have bye-elections by diverting electricity away from non-election constituencies.

The Indian electricity sector remains in dire straits with consumers and ?rms having to suffer through frequent rationing and outages. Despite some improvements over the last three decades (Pargal and Banerjee 2014), de?ciencies in the electricity sector have persisted, primarily due to the inability to increase production. For example, power generation in Uttar Pradesh (UP) in 2010 totaled 21 terawatt hours, a ?gure no higher than it was in 1995. As demand for electricity continues to grow, production shortfalls mean tight constraints on electricity supply.

In India, as in many other developing countries, electricity is largely managed by utilities that are owned and operated by the government. It is hence plausible that the failures of India’s electricity sector are ultimately due to ine?ciencies intrinsic to the country’s political processes. A large literature in political economics asserts that elected leaders prefer to allocate limited public resources, such as electricity, to achieve political rather than economic goals (Nordhaus 1975, Rogo? 1990, Dixit and Londregan 1998). Such political distortions in electricity supply may be costly economically if resources are diverted from productive to potentially unproductive uses.

However, while political interference is believed to be a major problem plaguing the Indian electricity sector, there is little empirical research that credibly documents the existence of political distortions, nor is there evidence con?rming that such distortions carry signi?cant economic costs. This lack of empirical evidence makes it di?cult to take an informed stance on recent debates about reforms of the Indian electricity sector1.

Elections and electricity supply

In this context, we present empirical evidence that the Indian electricity sector su?ers from political distortions that may carry large economic costs (Baskaran, Min and Uppal 2015). Using a dataset on about 4,000 state-level assembly constituencies, we explore whether Indian state governments distort the supply of electricity for electoral purposes. More precisely, we leverage the unpredictable occurrence of bye-elections to ask whether electricity supply increases as a result of electoral contests.

Since no data on electricity supply is available at the level of state constituencies, we use as a proxy night lights data from the US Air Force’s Defense Meteorological Satellite Program’s Operational Linescan System (DMSP-OLS). The night lights data has several advantages over administrative data. As electricity must be supplied to a geographical unit for the satellites to detect any light at night, DMSP-OLS provides an objective and accurate indicator for electricity supply that is available at very low levels of geography.

Electoral cycles in the Indian electricity sector are possible because the top managers of the electricity utilities are appointed by state governments and therefore have incentives to conform to their wishes. Electricity is also highly valued by consumers and ?rms, such that any increase may carry substantial electoral rewards. Third, an increase in electricity supply during bye-election periods may be a way for candidates, especially if they are new and untested, to signal to voters the extent of their in?uence with the state government and their ability to attract further resources from it in the future.

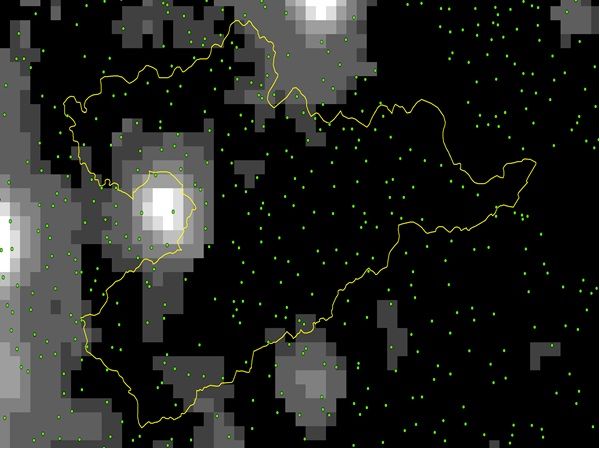

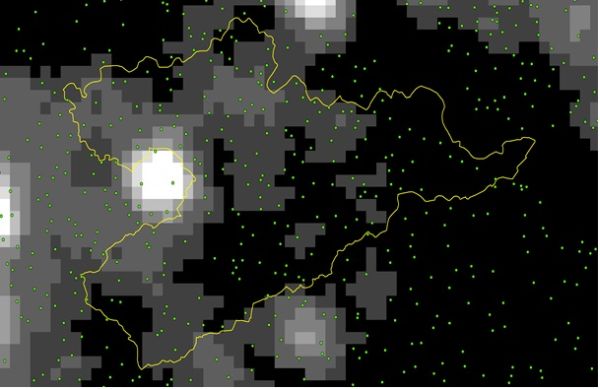

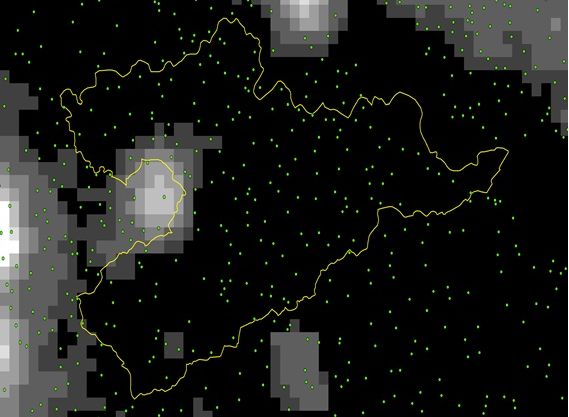

Figures 1a-1c provide some anecdotal evidence that bye-elections are opportune times for political leaders to influence electricity supply. In 2004, a bye-election was held in the constituency of Atrauli in central UP to fill a seat long held by Kalyan Singh, a prominent leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) who had twice served as chief minister of UP. Electricity provision increased dramatically in the bye-election year in Atrauli, with 72% of villages lit in 2004, up from 26% in the prior year. The rate returned to 24% the year after the election. The total light output surged more than fourfold in 2004 before returning to almost the pre-election baseline in the next year.

Figure 1a. Atrauli in 2003

Figure 1b. Atrauli in 2004

Figure 1c. Atrauli in 2005

For methodological reasons, we focus on bye-elections that are held due to the death of an incumbent member of the legislative assembly (MLA). They are unexpected and thus plausibly exogenous to economic developments or any other factors that may a?ect either the demand for or the supply of electricity within a constituency. Thus, all else equal, any sudden increase in electricity supply to constituencies that hold a bye-election can be plausibly linked to the electoral concerns of the state government.

Overall, our research documents a bump in electricity supply (or more speci?cally in light output) in a bye-election year. We ?nd furthermore that the bump is more pronounced in swing constituencies (where no party holds a comfortable lead in the prior general election), and if it is aligned with the state government (where the most recent incumbent belonged to the ruling party or ruling coalition). The bump is also larger if the incumbent state government commands only a narrow majority in the state legislature.

We also explore the broader welfare e?ects of the electoral manipulation in electricity. Our results suggest that the bump in bye-election constituencies is made up by reductions in non-election constituencies. Thus, elections do not lead to increased production in electricity overall but to a redistribution across constituencies. Furthermore, we observe no positive e?ects of the bump in electricity supply in bye-election constituencies on district-level Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Indicus Analytics Private Limited). Thus, the welfare effects, if any, of electoral manipulation are limited only to bye-election constituencies and there are no effects in the broader local region. Even for the bye-election constituencies, the effects are short-lived as the electricity supply reverts to the pre-election levels.

Implications for policy

Our results show that Indian state governments may distort the supply of electricity for electoral reasons across constituencies and that this interference carries economic costs. Moreover, it is plausible that the electoral distortions we document are only one aspect of broader attempts by politicians to interfere in the electricity sector. As demand for electricity will only grow in the foreseeable future, policymakers must address the shortcomings of India´s electricity sector if they want to maintain the high rates of growth the country has experienced since economic liberalisation in the early 1990s. The Electricity Act of 2003 sought to reform the power sector in India by introducing more competition in electricity provision by allowing entry of private firms. However, private entry into the sector, especially in distribution, has remained limited even after the reforms. The reform process should, therefore, be accelerated. Further, politicians’ control over sta?ng decisions by the electricity utilities should be limited; top managers may be appointed by a broader set of stakeholders. Alternatively, they can be given longer tenures to insulate them from any political pressure.

Notes:

- See, for example, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/06/24/switching-on-power-sector-reform-in-india.

Further Reading

- Baskaran, T, B Min and Y Uppal (2015), “Election cycles and electricity provision: Evidence from a quasi-experiment with Indian special elections”, Journal of Public Economics, Forthcoming.

- Dixit, A and J Londregan (1998), “Fiscal federalism and redistributive politics”, Journal of Public Economics, 68, 153–180.

- Nordhaus, W (1975), “The political business cycle”, Review of Economic Studies, 42, 169–190.

- Pargal, S and SG Banerjee (eds.) (2014), ‘More power to India’, The World Bank, Washington DC.

- Rogo?, K (1990), “Equilibrium political business cycles”, American Economic Review, 80 (21¬36).

03 August, 2015

03 August, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.