A key component of the National Rural Health Mission launched by the Indian government in 2005 was the introduction of a cadre of village-level Community Health Workers known as ASHAs. This column analyses the impact of the ASHA programme on childhood immunisation, and finds that ASHAs have had a positive impact by generating awareness regarding the need and availability of immunisation.

The Indian government launched the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in April 2005 with a vision to comprehensively improve the country’s public health delivery system. While the programme consisted of multiple components, a main provision of NRHM was the introduction of a cadre of village-level Community Health Workers known as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). While complex and multi-tiered, the public health set-up in India, prior to 2005, was considered too outstretched to provide outreach. At the time, existing health personnel included (i) Auxiliary Nurse-Midwife (ANM) and sometimes a male Multi-Purpose Worker (MPW) who worked out of health sub-centres, catering to a population of up to 4,500 individuals (approximately five villages), and (ii) an Anganwadi Worker who worked at the village-level but was focused on supplementary feeding services for children under six years of age. Given the pressures of a vast population, it was felt that another village-level worker was needed, to assist the ANM and the Anganwadi Worker in their tasks and to mobilise households in the utilisation of health services.

Role of ASHAs in the Indian public healthcare system

Community Health Workers are lay health workers who live in the communities they serve and act as a link between those communities and the public healthcare system. Their main task is to promote healthcare seeking behaviour through the provision of information and assistance, to ensure that health services that have a high potential to reduce mortality and morbidity are used by intended beneficiaries. In India, the ASHA is viewed as village-level machinery through whom a variety of health programmes are implemented. For instance, the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), which is a centrally-sponsored cash transfer scheme that incentivises pregnant women to deliver at healthcare institutions, pays a sum of money to the ASHA for every woman she takes to a health centre for delivery. Similarly, the National Leprosy Eradication Programme pays the ASHA a small sum for every leprosy case she identifies and registers.

An important task of the ASHA is to encourage and facilitate full childhood immunisation1. The ASHA is paid roughly Rs. 150 ($2.5 approx.) for every immunisation session she organises in a village (about one a month), and Rs. 75 ($1.25 approx.) per pulse-polio day.

NRHM guidelines instruct that an ASHA must be a married female between 25-45 years of age, and a resident of the village she serves. She is a voluntary health worker who is not a paid a fixed salary, but is paid on a per-task basis. Between 2005 and 2014 roughly 9 lakh (0.9 million) ASHAs were hired across the country. Given that the recurring expenses of the Indian government towards ASHAs can be up to Rs. 14,000 ($233 approx.) per ASHA in a year, an evaluation of the programme is critical from a public-policy point of view. In my research, I examine the impact of the ASHA programme on a primary task of public health machineries the world over - the provision of childhood immunisation (Rao 2014).

Estimating impact of ASHAs on childhood immunisation

Quantifying the impact of a large-scale health intervention like this one is a challenging task, post-implementation. An ideal scenario, from a programme evaluation viewpoint, would have entailed ASHAs being piloted in a few randomly selected regions, followed by a comparison of outcomes between comparable (at baseline) regions with and without ASHAs. While this was unfortunately not the case here, since the programme was rolled out simultaneously all across the country, the intensity with which the programme was introduced varied markedly in different parts of the country, following a policy statement issued by the government. In 2005, the Indian government mandated that the ASHA programme be heavily focused on 18 “high focus Indian states”2 that were lagging behind on various public health indicators. The central government directly funded the implementation of the programme in these states where it directed that there be 1 ASHA per population of 1,000 people. Funds under the NRHM were also released to non-focus states but they were not tied to this directive and were allowed to flexibility design their own package of interventions to achieve public health goals.

As a result, when the District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS) collected data from a representative sample of villages in 2008, 74% of the villages from high-focus states had an ASHA as opposed to 33% in non-focus states. By 2008, 4.6 ASHAs per health sub-centre had completed the first round of training in high-focus states whereas this figure was 1.6 in non-focus states. These differences in the presence of ASHAs, between high & non-focus states, is clearly a fall-out of government policy and my analysis makes use of this variation to present preliminary estimates of the impact of the programme on childhood immunisation.

Childhood immunisation trends

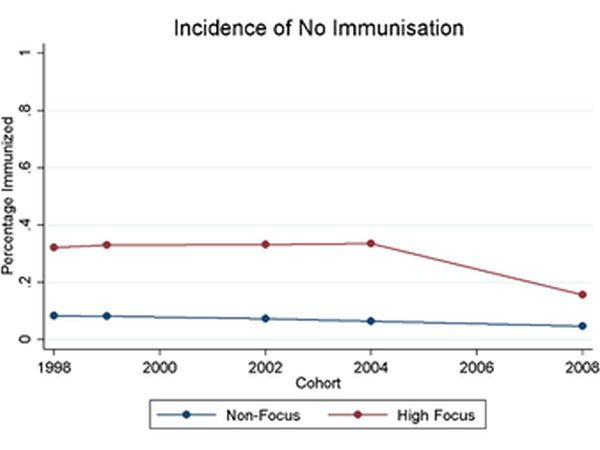

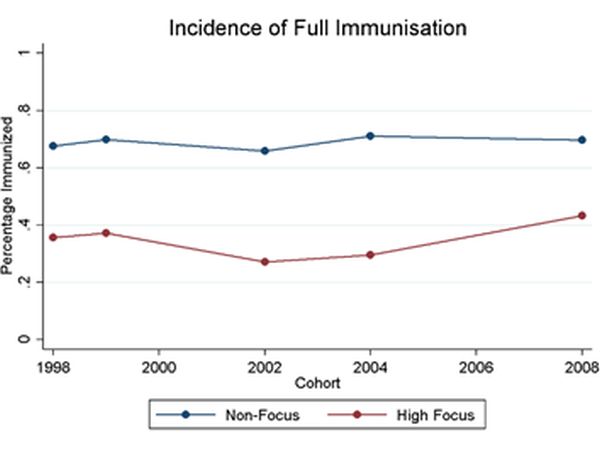

Figures 1 and 2 below compare immunisation trends in high-focus and non-focus states3 for cohorts of infants born between 1998 and 2008. While immunisation levels have historically been significantly higher in non-focus states for the period prior to the introduction of the ASHA programme (1998-2004), immunisation trends in both sets of states were evolving at a fairly constant rate. However, after the introduction of the programme in 2005, there was a sharp decrease in the incidence of ‘no immunisation’ and sharp increase in the incidence of ‘full immunisation’ in high-focus states, relative to non-focus states, which more or less progressed at their usual rate. For instance, there was nearly a 14 percentage-point spike in the incidence of ‘full immunisation’ in high-focus states when we compare the cohort of infants born after 2005 with the cohort born just before. In contrast, for non-focus states ‘full immunisation’ rates fell by around 2 percentage points.

Figure 1. Incidence of ‘no immunisation’ in non-focus and high-focus states

Figure 2. Incidence of ‘full immunisation’ in non-focus and high-focus states

I estimate the increase in immunisation in high-focus states before and after the ASHA programme. Considering each routine vaccine separately and looking at full and no immunization, I find that following the programme, the incidence of immunisation in high-focus states increased by 14-22 percentage-points.

To account for confounding factors, I difference out the increase that was likely to have occurred even in the absence of the programme, by using the trend in non-focus states as a proxy, and by accounting for a host of plausible confounders in the analysis. For instance, using village and sub-centre level data from the DLHS-3 survey, I consider the possibility that other health-related infrastructure like government dispensaries, private clinics, sub/primary/community health centres etc. could have been built more intensely in high-focus than non-focus states in the period coinciding with the ASHA worker programme. I also examine how other NRHM provisions were adopted in high- versus non-focus states like the receipt and utilisation of “untied funds” at different levels and “Village Health and Sanitation Committees” at the sub-centre level. Apart from the coverage of Anganwadi centres which increased substantially more in high-focus states in comparison to their non-focus counterparts during this period, on account of all other related infrastructure, non-focus states benefitted more than high-focus states. Thus, looking at both infrastructural provisions not directly related to the NRHM as well as NRHM provisions, it seems to be the case that a large part of the improvements in immunisation, in high-focus states, are attributable to ASHAs and their outreach efforts.

ASHAs effective in generating awareness regarding immunisation

In the DLHS-3 survey conducted in 2007-08 when mothers in high-focus states were asked about the primary reasons for not getting their child immunised, a significantly smaller fraction of them stated awareness-related reasons like not being aware of the need for immunisation or not knowing the time/place of immunisation as being impediments, when compared to mothers interviewed in 2002-04. Such progress was not seen among mothers of non-immunised children in non-focus states. Contrast this with impediments more indicative of the physical supply of infrastructure, for instance, the distance to an immunisation facility. There was a close to 4 percentage-point decline in the fraction of mothers of non-immunised children who stated that the ‘place of immunisation was too far to go to’ in non-focus states but a 1 percentage-point increase in the fraction of mothers who cited this reason in high-focus states.

Overall, ASHAs, since their introduction in 2005, seem to be working well in high-focus states as village-level mobilisers of households, to utilise the existing public health set-up, despite a lack of complementary improvements in other components of the supply chain of immunisation provisions in those states.

Notes:

- According to Indian guidelines, this includes one dose of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, three doses of Diphtheria Pertussis and Tetanus (DPT) vaccine, one dose of Oral Polio Vaccine 0 (OPV 0), three doses of OPV vaccines and one measles vaccine by the time the child is one year old.

- The 18 high-focus Indian states are Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura, Nagaland, Mizoram, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir.

- Sample is confined to rural infants as the programme is operational only in rural areas.

Further Reading

- Rao, Tanvi (2014), ‘The Impact of a Community Health Worker Program on Childhood Immunization: Evidence from India´s ´ASHA´ Workers’.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, ‘NRHM Framework for Implementation (2005-2012)

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), ‘District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-1, 2 & 3)

27 June, 2014

27 June, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.