In certain socio-cultural contexts, onset of menstruation (menarche) adversely affects educational attainments of girls. This article shows that onset of menses before age 12 causes a 13% decrease in school enrolment rate in India. Healthier girls have higher learning outcomes at age 12, but they also start menstruating earlier and are more likely to drop out of school, such that their initial health advantage over other girls in their cohort disappears.

Despite universal primary school enrolment in India, many adolescent girls drop out of school after completing eight years of compulsory schooling. A notable gender gap in school enrolment emerges and grows during the teenage years (Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), 2018). What explains the appearance of a gender gap in schooling as children enter adolescence? Some of the existing explanations focus on access to school infrastructure (ASER, 2018), the burden of housework (Sundaram and Vanneman 2013), and returns to education for girls (Chamarbagwala 2008). In my recent work, I add to this literature by showing that, in the Indian context, the onset of menstruation (menarche) ─ a universal biological event ─ is an important piece of the puzzle (Khanna 2019).

Menarche is not only a critical biological change but also an event of immense significance in the Indian sociocultural milieu. Norms of a girl's engagement with her family and her community alter dramatically when she starts menstruating (Seymour 1999). Menarche is marked by rituals and celebrations (Dharmalingam 1994), and is followed by restrictions on the girl's day-to-day activities during her menses (Mahon and Fernandes 2010, Kumar and Srivastava 2015). Menarche marks the girl’s transition into womanhood and the beginning of a critical period in her life when “she has acquired the capability to reproduce but she has no authority to do so" and her “vulnerability is at its peak" (Dube 1988). Restricting her mobility is one way in which her safety is ensured. In this cultural context, I demonstrate that an earlier onset of menarche has a large and significant impact on school enrolment.

Effect of early menarche on enrolment

To estimate the effect of early menarche on school enrolment, I use data on 1,000 representative children in Andhra Pradesh (now Andhra Pradesh and Telangana). The children were interviewed at ages eight, 12, 15, 19, and 22. Importantly, the second round of the survey, during which children were about 12-years old, asked girls if they had started menstruating yet.

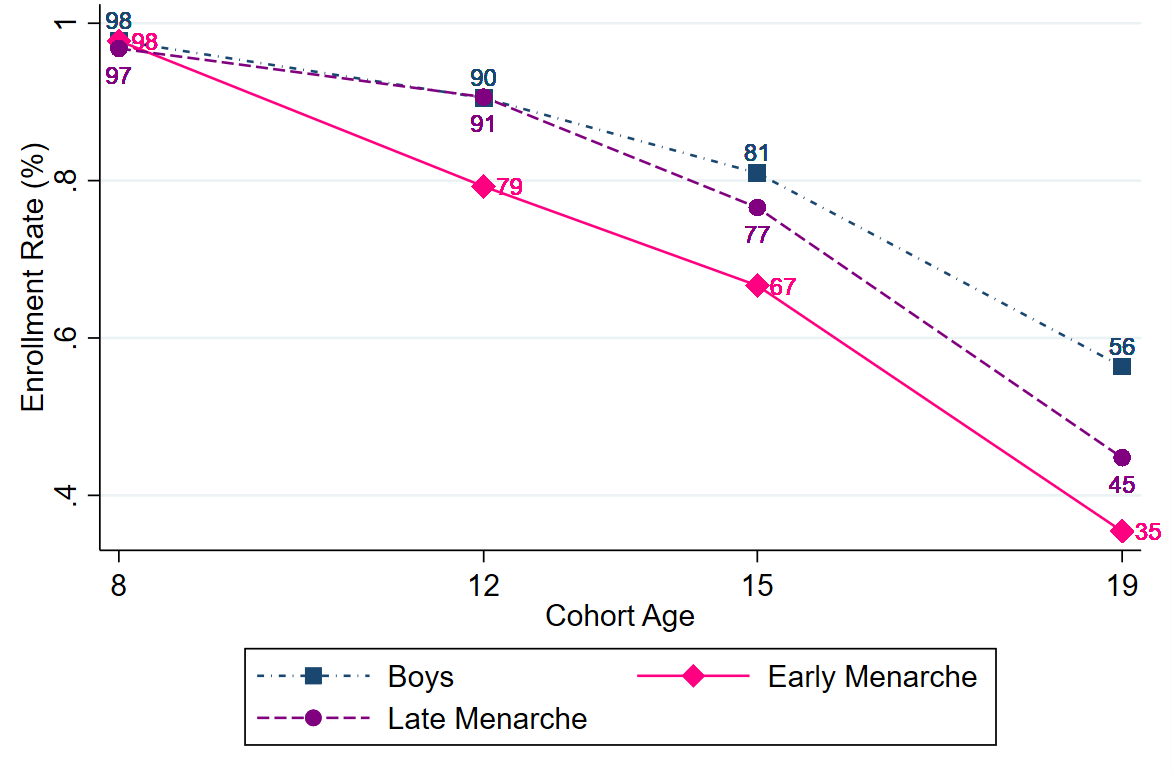

Figure 1 charts the trends in enrolment for three groups of children: girls who reached menarche before age 12 (girls in the early menarche group), girls who reached menarche after 12 (girls in the late menarche group), and boys. While the enrolment rate does not differ across three groups of children at age eight, there is a precipitous drop in the enrolment rate of girls in the early menarche group between ages eight and 12. Trends in enrolment for boys and girls in the late menarche group are almost identical.

Figure 1. Enrolment rate, by gender and menarche status

I use a difference-in-differences design1 that takes advantage of the variation in the timing of menarche within the same age cohort. The enrolment status of girls who had not reached menarche by age 12 is the counterfactual for those who experienced an earlier menarche. A little more than a quarter of the surveyed girls had reached menarche before age 12. I find that starting menses before age 12 leads to a 12 percentage-points decline in the school enrolment rate, and this decline is 13% relative to the enrolment rate of girls in the late menarche group at age 12 (91%).

The magnitude of the estimated effect of early menarche on school enrolment is sizeable. Indeed, it is comparable to the effect of various education-related policies and reforms in India. For instance, a school-latrine construction initiative increased middle school enrolment by 8% (Adukia 2017). Providing free school lunch to primary school students increased the primary school enrolment rate by 7.3% (Kaur 2016), whereas giving free bicycles to school-going teenaged girls increased their school enrolment by 32% (Muralidharan and Prakash 2017).

How can my results be reconciled with the evidence from Oster and Thornton (2009) that menstruation accounts for only 0.4 missed school days among adolescent girls in Nepal? An analysis of the time-use patterns of the sample of girls who are still in school at age 12 shows that girls in the early menarche group spend as much time at school as girls in the late menarche group. Taken together, these results suggest that it is the onset of menstruation, and not menstruation per se, that affects schooling.

Variation in the effect of early menarche on enrolment

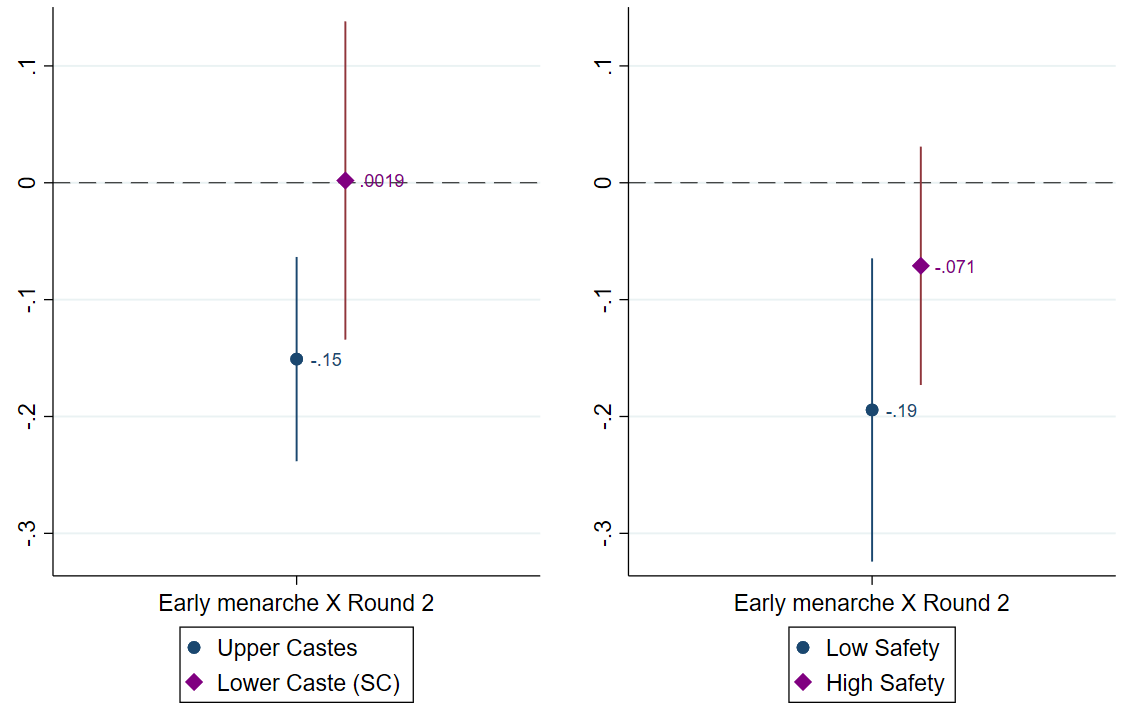

In India, the notion of a family’s honour is closely associated with the behavior of women in the family, and this concern is more prevalent among upper castes (Eswaran, Ramaswami and Wadhwa 2013). Since the concerns regarding family’s honor and restrictions on women’s mobility (and schooling) are more relevant after menarche, the effect of early menarche should be more pronounced among upper castes; this is the pattern described in Figure 2. Early menarche alters young girls’ experiences to the extent that they are less likely to feel safe in their community. The effect of early menarche on enrolment is also more pronounced among those girls who reside in communities where the average perception of safety is lower among children (only boys are considered).

Figure 2. Variation in the effect of early menarche, by safety and caste

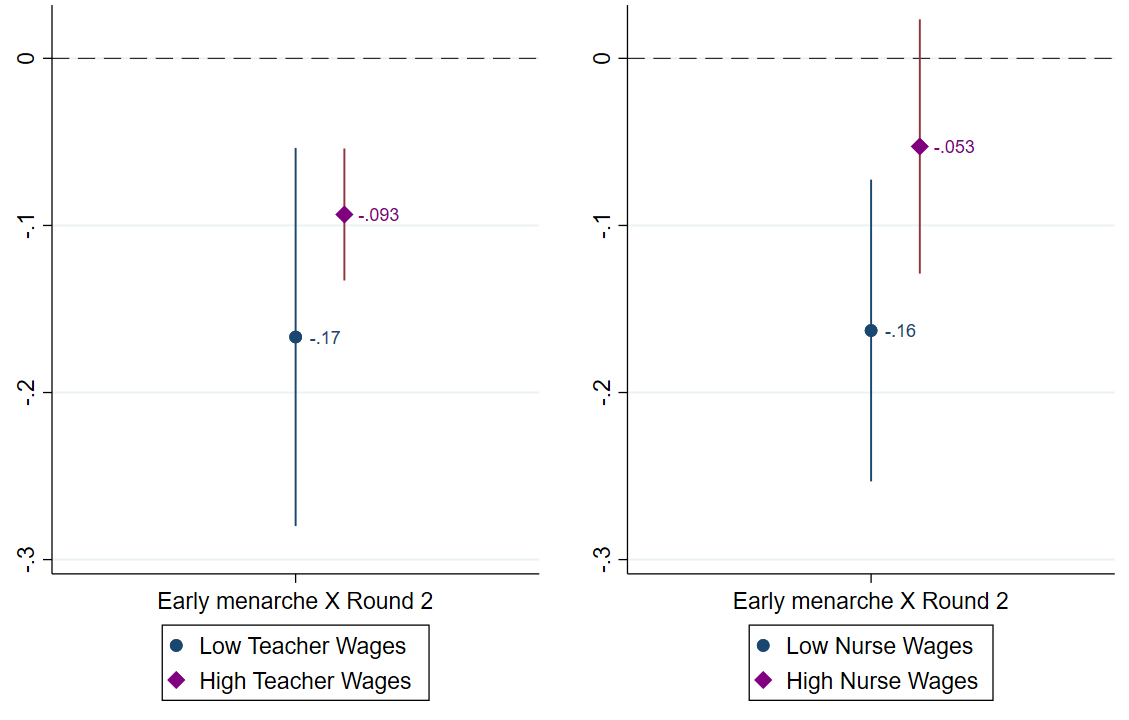

While local cultural factors impede adolescent girls’ schooling, local economic opportunities for women encourage it. Figure 3 shows that the negative impact of early menarche on schooling is muted in those communities that have higher wages for typically female-dominated professions (nursing and teaching).

Figure 3. Variation in the effect of early menarche, by wages of female dominated professions

Virtuous cycle of human development and menarche

The virtuous cycle set in motion by better childhood nutrition is a critical tool for improving welfare as gains in early nutrition foster higher schooling, adult skills, and wages (Almond and Currie 2015). Among girls, childhood nutrition is known to be linked to their menarcheal timing, such that better nourished girls tend to reach menarche before others in their cohort. The link between better nutrition and early menarche is confirmed in the data, and girls who reach menarche before age 12 are about five centimetres taller and over two kilograms heavier than their peers. However, they are also more likely to drop out of school after menarche, and potentially lose some of this initial health advantage. Certain social norms, therefore, may undermine the virtuous cycle of human development for girls.

What it means for policy

Given the sizeable impact of early menarche on school enrolment, improving access to menstrual hygiene management products seems to be the most relevant policy response. However, the existing evidence on the impact of these products is not promising (for instance, Oster and Thornton 2011, Benshaul-Tolonen et al. 2019). At the same time, safety concerns and social norms appear to be an important barrier to adolescent girls’ schooling. Indeed, interventions that address these concerns have been successful in encouraging female enrolment (for instance, Adukia 2017, Muralidharan and Prakash 2017). As I show in this study, familial and social settings that restrict the scope of a girls’ experiences after menarche can undercut the virtuous cycle of human development for girls. As such, a clear policy lever to promote girls’ schooling would be social campaigns designed to challenge gender-restrictive norms.

Note:

- A difference-in-differences design calculates the impact of early menarche on school enrolment status by comparing the difference in the average school enrolment across girls in the early and the late menarche groups at age eight (when neither group had reached menarche) with the difference in the average school enrolment at age twelve (when only girls in the early menarche group had reached menarche). If one assumes that the two groups of girls would have dropped out of school at the same rate in the absence of a change in their menarche status, the difference between the two differences described above (that is, difference-in-differences) gives the impact of early menarche on school

Further Reading

- Adukia, Anjali (2017), “Sanitation and education”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2):23-59.

- Almond, D and J Currie (2011), ‘Human capital development before age five’, in Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 4, pp. 1315-1486, Elsevier.

- ASER (2018), 'Annual Status of Education Report, 2017: Beyond Basics', ASER Centre, New Delhi.

- Benshaul-Tolonen, A, Z Garazi, E Nyothach, C Oduor, L Mason, D Obor, KT Alexander, KF Laserson and PA Phillips-Howard (2019), ‘Pupil Absenteeism, Measurement, and Menstruation: Evidence from Western Kenya’, CDEP-CGEG Working Paper No. 74, Colombia University.

- Chamarbagwala, Rubiana (2008), “Regional returns to education, child labour and schooling in India”, The Journal of Development Studies, 44(2):233-257. Available here.

- Dharmalingam, A (1994), “The Implications of Menarche and Wedding Ceremonies for the Status of Women in a South Indian Village”, Indian Anthropologist, 24(1):31-43.

- Dube, Leela (1988), “On the Construction of Gender: Hindu Girls in Patrilineal India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 23(18):WS11-WS19.

- Eswaran, Mukesh, Bharat Ramaswami and Wilima Wadhwa (2013), “Status, Caste, and the Time Allocation of Women in Rural India”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61(2):311-333.

- Kaur, R (2016), 'There are Free Lunches in Life: Impact of Mid Day Meal Program on School Enrollment in India', University of Texas at Austin.

- Kumar, Anant and Kamiya Srivastava (2011), “Cultural and social practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls”, Social Work in Public Health, 26(6):594-604.

- Khanna, M (2019), ‘The Precocious Period: The Impact of Early Menarche on Schooling in India’, Gui2de Working Paper Series No. 05, Georgetown University.

- Mahon, Thérèse and Maria Fernandes (2010), “Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: a neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programmes”, Gender and Development, 18(1):99-113.

- Muralidharan, Karthik and Nishith Prakash (2017), “Cycling to school: increasing secondary school enrollment for girls in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(3):321-350.

- Oster, Emily and Rebecca Thornton (2011), “Menstruation, Sanitary Products, and School Attendance: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1):91-100.

- Sundaram, Aparna and Reeve Vanneman (2008), “Gender differentials in literacy in India: The intriguing relationship with women's labor force participation”, World Development, 36(1):128-143.

04 December, 2019

04 December, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.