Youth underemployment, especially among less educated populations perpetuates poverty. Despite the importance of youth unemployment, there is little knowledge on how to create smooth school-to-work transition and or how to improve the human capital of those who can no longer be sent back to school. This column presents evidence supporting positive returns from having access to and completing a vocational training course for women residing in low-income households in New Delhi.

The most recent World Development Report on jobs notes that, “200 million people, a disproportionate share of them youth, are unemployed and actively looking for work” (World Development Report 2013). Despite the importance of youth unemployment in low-and-middle income countries, there is little knowledge on how to create employment opportunities and or how to improve the skills of those who can no longer be sent back to school. The National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) of India and international organisations such as the World Bank, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Department for International Development (DFID), UK Government, increasingly consider vocational training to be one promising avenue through which young adults, particularly women, can acquire marketable skills that will enable them to secure employment.1 Despite the large-scale expansionary policies undertaken by these organisations aimed at increasing access to vocational training programmes, there is very little empirical evidence on the returns to such training programmes from developing countries. Experimental evidence is particularly scarce and there is virtually no evidence on the medium-run effects of such programmes in developing countries2.

The high levels of economic growth accompanied by rising inequality and skill shortage as experienced by India makes it an important setting to evaluate the effectiveness of labour market training programmes. The Finance Minister of India, during his Budget Speech in the Indian Parliament in 2008-2009, announced that: “there is a compelling need to launch a world class skill development programme in mission mode that will address the challenge of imparting the skills required by a growing economy”. Recent surveys conducted by the World Bank and the Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) ally these concerns (Blom and Saeki 2011, FICCI 2011). The Economist in a recent opinion piece adds to this concern by stating, “And a lot of training is required. Many of India´s young leave school ill-prepared even for rudimentary jobs.” (The Economist, May 2013)3

The intervention

In a recent paper (Maitra and Mani, 2013) we try to address some of these issues. We teamed up with two NGOs based in Delhi, Pratham and Satya, and designed an intervention in vocational training programme in stitching and tailoring services. The programme involved providing a heavily subsidised six-month course in stitching and tailoring to women between ages 18 and 39 years, residing in poor slum communities of New Delhi in India. Eligible women were invited to apply to the programme and from within the pool of applicants, a lottery determined each woman´s assignment into one of the following two groups: treatment group (received access to this course) and control group (did not receive access to this course). Participants in the programme committed up to two hours per day in a five-day week for six-months, starting August 2010. All selected participants were required to deposit Rs. 50 per month for continuing in the programme, with a promise from the NGOs that women who stayed through the entire duration of the programme would be repaid Rs. 350. This feature is unique to the programme and was introduced by the implementing NGOs to increase commitment and encourage regular attendance. The actual programme started during the second/ third week of August 2010 and continued through to the last week of January 2011.

Short-and-medium-run impact estimates

We combined the pre-intervention data with two rounds of follow-up data (conducted 6 and 18 months after programme completion) to estimate the short-and-medium-run effects of the programme. We find that within six months of programme completion, women who were offered the training programme are 6 percentage points more likely to be employed, 4 percentage points more likely to be self-employed, work 2.5 additional hours per week, and earn 150% more per month than women in the control group. Using a second round of follow-up data collected 18 months after the completion of the programme, we find that the positive effects of the programme on employment, hours worked, and earnings are all sustained into the medium-run. We also find that women who had access to this training programme are more likely to own a sewing machine (a measure of entrepreneurship) in the post-training period. Further, programme benefits are substantially larger for women who completed the entire programme.

Barriers to programme completion

Only 56% of the women assigned to the treatment group complete the programme and received the certificate at the end.4 This suggests that there are barriers to programme completion other than credit constraints which are partially alleviated through subsidised access to the programme.

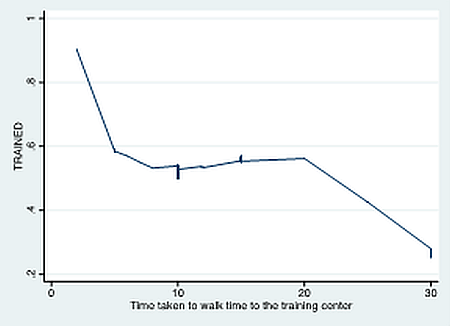

We are able to identify three crucial barriers to programme completion: credit constraints, local access and lack of child-care support. First, while the Satya/ Pratham programme was not the only programme available to these women, only 13% of the women assigned to the control group take up and complete courses offered by other providers. This confirms the importance of credit (and resource) constraints as a significant barrier to programme participation and completion. Second, distance to the training centre captured by the time taken to walk to the training centre is a significant barrier to skill accumulation – Figure 1 depicts the strong negative relationship between distance and programme completion. Indeed the importance of local access and distance was reiterated to us in informal conversations with different stakeholders. Women in India, particularly those belonging to the socio-economic class from where the programme applicants were drawn, typically face a large number of restrictions on mobility. They need permission to use public transport and often need permission to visit family and friends. So while there are similar programs offered by private organisations and the government, these programs are often centralised, implying that participants have to travel long distances to reach the training centres. This increases the cost of programme attendance, which can act as a significant barrier to skill accumulation.

Figure 1. Distance to training center and programme completion<

Third, we also find that relative to unmarried women, married women with the mother-in-law present in the household are 29 percentage points more likely to complete the programme. The fact that married women with co-resident mother-in-laws are more likely to complete the programme is not surprising as co-resident mother-in-laws can provide low cost child care -- this is a common arrangement in India and many other developing countries.

Finally, using a simple cost benefit analysis we show that there are considerable gains from both continuing the programme in the same location and replicating the programme in a different location. The cost-effectiveness analysis shows that the cost of the programme can be recovered in less than four years.

Lessons for the future

Despite the well-known fact that increasing the income level of women will have a strong positive impact on both current welfare and the welfare of the next generation, little is known about how to best help women in low-income households and communities in developing countries to acquire skills, find jobs and increase earnings.

There are a number of potential different policy options. One would be to inject credit and reduce the credit constraints that appear to hamper the ability of women to take advantage of their entrepreneurial skills. Indeed the entire microfinance revolution was built around this model - provide microloans that will serve as working capital for setting up small businesses leading to increased income over time. However, recent studies are increasingly skeptical of the success of such a model of development.5 Evidence also suggests that capital injections generated large profit increases for male microenterprise owners, but not for female owners. One plausible explanation for these differential effects is that cash injections directed at women are often confiscated by their husbands and or other members of their household resulting in considerable inefficiencies.

One alternative tool for expanding the labour market opportunities for young women in these settings is vocational or skills training. This could help women learn a trade, acquire the skills needed to take advantage of employment opportunities, and create successful small businesses. One additional advantage of this kind of training is that it results in human capital accumulation that is specific to the person undertaking the training and that cannot be confiscated by their spouse. Despite pro-training policies undertaken by countries in several developing nations, the economic benefit from participating in vocational training programmes is relatively unknown. Investing in vocational training programmes can result in substantial economic gains for women in low-income households in developing countries.

Credit constraints, distance to the training centre, and availability of child care support in the household will severely constrain women from participating in and completing training programmes of any kind, not just vocational training in stitching and tailoring. Future active labour market programmes and policies must be designed keeping these barriers in mind.

Notes:

- India, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Uruguay are some of the developing countries that have designed such programmes. See Annex 2 of Betcherman, Olivas, and Dar (2004) for a complete list of countries and details on skill building and other labour market training programmes.

- Experimental evaluation of labour market training programmes in developing countries is fairly rare – two exceptions are Card, Ibarraran, Regalia, Rosas, and Soares (2011) and Attanasio, Kugler, and Meghir (2011). Neither of the studies captures medium-run effects of the programme.

- “Angry Young Indians”, The Economist, May 11 – 17th, 2013, page 12.

- Similar, low rates of programme completion are observed in other developed and developing countries as well - Germany (69%), Dominican Republic (60%), Uruguay (51%), and Peru (60%).

- See for example Banerjee, Duflo, GlennerstFurther Reading

- Betcherman, G., K. Olivas, and A. Dar (2004), “Impacts of Active Labor Market Programs: New Evidence from Evaluations with Particular Attention to Developing and Transition Countries”, Social protection discussion paper no. 0402, World Bank.

Watch a video of Puskhar Maitra presenting the underlying research at the 4th IGC ISI India Development Policy Conference (December 17-18, 2013, New Delhi)

Further Reading

- Attanasio, O., A. Kugler, and C. Meghir (2011), “Subsidizing Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Youth in Colombia: Evidence from a Randomized Trial”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3, 188–220.

- Blom, A., and H. Saeki (2011), “Employability and Skill Set of Newly Graduated Engineers in India”, Discussion paper, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5640.

- Card, D., P. Ibarraran, F. Regalia, D. Rosas, and Y. Soares (2011), “The Labor Market Impacts of Youth Training in the Dominican Republic: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation”, Journal of Labor Economics, 29(2), 267–300.

- Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, R. Glennerster and C. Kinnan (2013), “The Miracle of Microfinance: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation”, Discussion Paper, MIT.

- FICCI (2011), “FICCI Survey on Labour / Skill Shortage for Industry”, Discussion paper, FICCI.

- Maitra, P. and S. Mani (2013), “Learning and Earning: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation”, Fordham Discussion Paper Series DP2013-02, Fordham University, Department of Economics.

- World Development Report (2013), ‘Jobs’, World Bank.

15 July, 2013

15 July, 2013

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.