In Part I of this piece, the authors made broad recommendations to guide the government’s response to Covid-19 in India. In this part, they identify five salient population groups that are particularly vulnerable to the economic and health shocks arising from the current crisis, and regions where relief effort needs to be concentrated.

In Part I of this piece, we discussed broad recommendations to guide the government's response to the pandemic in India. In this part, we discuss the economic impact of the current crisis on particularly vulnerable groups. We identify five salient groups who are vulnerable to the economic and health shocks arising from SARS-COV-2: children, women, migrants, daily-wage earners, and self-employed individuals. For each of the groups, we identify the regions where relief effort needs to be concentrated and discuss how to formulate policies to assist them. We also discuss the economic effects of lockdowns on salaried workers: while they are seen to be less vulnerable, some of them (such as factory workers and other blue-collar workers) may face significant economic hardship from extended lockdowns.

Children

Early childhood malnutrition is a rampant health problem in India, manifested in low height-for-age (stunting), low weight-for-age (underweight) and low weight-for-height (wasting). There is clear evidence from several parts of the world that early childhood malnutrition has lasting impacts on individuals throughout their life course. Malnourished children are more likely to have lower learning capacity, lower productivity, higher morbidity, and greater risk of non-communicable diseases, after accounting for all other risk factors.

India is home to more than a third of all stunted children in the world, and 38% of all children between 0-5 years were stunted in 2015-16, according to figures from the National Family and Health Survey. This is already a public health crisis of giant proportions. Under conditions of a pandemic and a lockdown, these children are not only themselves more vulnerable to the disease, but also to a worsening of their malnutrition status (due to the loss of their parent’s livelihoods, and the reduced availability of food and medical resources), both of which have adverse implications for their lives lasting well into their adulthood.

There are also significant caste gaps in the prevalence of stunting. In 2015-16, 32% of Hindu upper caste children were stunted, compared to 45% of SC-ST (Scheduled Caste and Tribe) children and 39% of OBC (other backward classes) children. Calculations based on longitudinal data (Deshpande and Ramachandran 2020) reveal that children who were stunted at the age of one are more likely to be stunted at age 15 (Deshpande and Ramachandran 2020). Children who are stunted at age one also have persistently lower learning outcomes later in school, relative to children who were not stunted at age one. Given that SC-ST children are significantly more likely to be stunted, and likely to remain stunted, the adverse consequences on their lives would be that much more severe.

The provision of a social safety net through cash and in-kind transfers can go a long way in mitigating the effects of negative shocks in early childhood (Dasgupta 2017). We support recommendations that have already been made that the government tap into its network of anganwadi and ASHA (accredited social health activists) workers to deliver school meals to children at their homes during lockdowns involving school closures, particularly through the disbursement of dry rations (such as rice, pulses, eggs), ready-to-eat food packets, fruits and nuts. The anganwadi workers already have a mechanism of delivering take-home ration for pregnant and lactating mothers and for very young children. This could be extended to include preschool-aged children and midday meal beneficiaries and also the amount of take-home ration could be increased.

In doing so, the health of the anganwadi workers should be prioritised. Proper masks and sanitisers should be disbursed to these health workers with full payment for their services. It is important for the government to realise that these healthcare personnel belong to the high-risk category for contracting and spreading the disease from close contact with patients. The frontline health workers should be given the recommended protective gears to ensure both their safety and that of the people they are dealing with, which can vastly improve their efficacy on the ground.

Women

A major concern during this lockdown is access to contraceptives and family planning products due to the initial shutting down of their manufacturing units and the reduced presence of health workers. Previous research has found that natural disasters have led to significant increases in childbirth rates and reduced spacing between successive births, particularly for uneducated women (Nandi et al. 2018). This may lead to significant demographic challenges such as reduced investments in children, particularly girls. The role of the social safety net is critical in ensuring that the cost of this crisis does not fall disproportionately on women. Additionally, government should minimise disruptions in reproductive healthcare, build inventories of contraceptives, ensure access to sanitary products, and offer counselling and support for reproductive healthcare needs through the continued presence of health workers on the ground.

Another horrific impact of the lockdown has been a rise in domestic and intimate partner violence in the US, the UK and China, among other countries, increasing the risks to women’s lives. The first step is for administration and law enforcement agencies to recognise the gravity of the problem, to listen to women and to sympathise with them. At this time, more than at any other time, women need assurance that they will be heard, and that help will be sent if they fear for their or their children’s lives. Reaching women in distress needs to be classified as an essential service. The police will have to be told in the strictest terms that they have to respond to distress calls from women, regardless of their class, caste or religion.

Migrant workers

The media has justifiably spent considerable attention on migrant workers and how this group is specifically vulnerable to the crisis. In light of this, it is important to reflect on the number of migrant workers and their geographic concentration, so that relief efforts focusing on this group can be better designed and targeted. According to Census 2011 data, about 41 million individuals or about 8.5% of the total population of workers are migrant workers.1 Some are temporary migrants (roughly 3.5% of all workers) who are especially vulnerable to the crisis, since they live away from home and are mostly engaged in informal sector work. We focus on temporary migrants, as opposed to permanent migrants, who are living at their usual homes.2

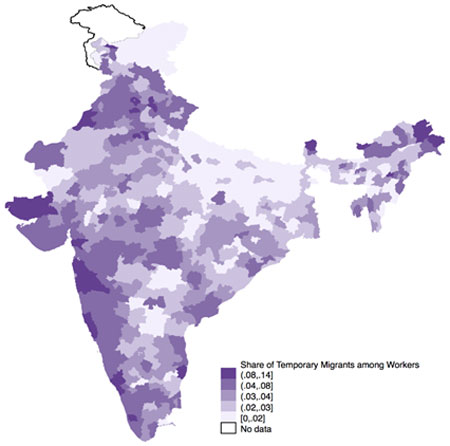

Figure 1. Share of temporary migrants among workers

To help identify the regions of the country with high concentration of temporary workers we plot the proportion of such workers across districts using a heat map. We believe the spatial pattern of the proportions as depicted in the figure would be very close to what it is today. We find that most of the temporary migrant workers are located in the western and south-western coastal districts and some districts in Haryana, Punjab, and Himachal Pradesh.

It is especially hard to provide assistance to this group since they face both a liquidity crisis as well as higher prices of essential commodities due to supply chain disruptions. Even though they can, in principle, access the central government portion of their PDS (public distribution system) rations from the fair price shops at their location of work, these individuals often do not carry their ration cards with them. Therefore, though our proposed policy of cash transfer may help them with liquidity, they may still not have adequate access to essential items. To ensure adequate access to food, the states should arrange for community kitchens, especially in the districts with large populations of migrant workers. There is also room for some creative solutions with respect to this issue. Kerala, for example, is trying to home deliver food to quarantined people. This can be specifically arranged for the migrant population as well. Moreover, public buildings such as indoor stadia, school buildings, etc., can be used to provide them shelter during lockdown. Further, many migrant workers who work in small factories or in the gig economy (drivers in app-based cab services, etc.) face uncertainty about when their work will resume after the lockdown is over. Consequently, they may prefer to travel back home. Arranging for their safe transport would be an essential task of state governments. Evidently, it is important to identify the possible solutions that fit the context of a state and organisational capacities of its government, prior to future outbreaks so that explicit announcements can be made in advance before panic sets in. Our proposed Pandemic Preparedness Unit can devote their attention on this to avoid chaos at the time of need.

Daily-wage earners

The population of casual labourers who earn daily wages constitute another related, but distinct category of vulnerable people. During lockdown they are hit the hardest as their livelihood gets immediately disrupted. A significant proportion of workers in India belong to this category. We use the PLFS (Periodic Labour Force Survey) in 2017-18 to calculate the proportions of daily wagers in urban and rural areas separately.3

The share of casual labourers who earn daily wages in the working population is 14.5% in urban areas and 29% in rural areas. We are especially concerned with daily wagers in urban areas, many of whom work on construction sites, and are engaged in other unskilled or semi-skilled activities, and who face immediate unemployment. Additionally, the effect of inflation in essential commodity prices would be much larger on them as compared to their counterparts in rural areas due to supply chain disruptions.

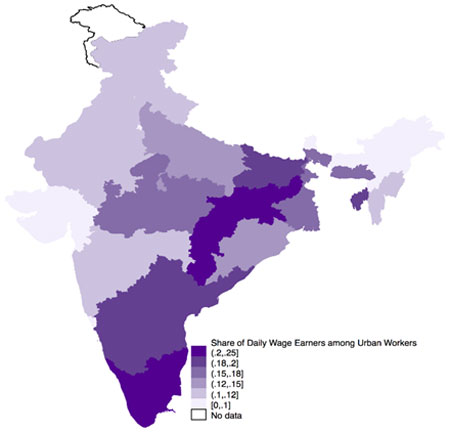

Figure 2. Share of daily-wage earners among urban workers

We show the geographic variation at the state level of the proportion of daily wagers in the urban area in Figure 2.4 We find that southern states and Chhattisgarh have relatively high shares of daily wage earners in the urban area. These states especially need to be mindful of the welfare of this group. Our proposal of cash transfer along with provision of essentials through PDS would be an important step in mitigating their distress during the lockdown.

Self-employed individuals

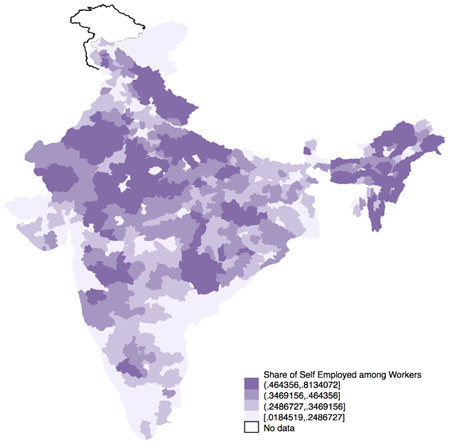

Self-employed individuals, including farmers and individuals engaging in household production or retail services, constitute another large segment of our working population who face uncertainty at this time of lockdown. According to Census 2011, about 30% of workers are self-employed. Figure 3 plots the proportion of self-employed individuals across districts of India, identifying those districts where this group of workers are concentrated. We find that many districts in the north-eastern states of India, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh have large self-employed populations.

Figure 3. Share of self-employed among workers

The policy response for this group of people should be similar to the one for daily-wage labourers. Additionally, the government should consider waiving rental payments for retail shops in locked-down areas. For the farmers, we should ensure that agricultural production should not get disrupted and they are able to source their necessary inputs.

Salaried workers

Regular/salaried workers constitute around 18.5% of the workforce.5 They are more skilled and earn roughly double the wages of casual or self-employed workers. Two-thirds of regular/salaried workers are employed in services and almost three-quarters are concentrated in urban areas (about 75%).

The government recently announced that it would make additional contributions to employee provident funds and allow for early withdrawals; while this can ease life for salaried workers over the next 1-3 months, it will be insufficient in the long run. Globally firms have already started cutting wages for workers – such as Qantas, Indigo, Koovs, Oyo to name a few. The Indian government has asked firms to not lay off workers, but cost management practices within firms may be the deciding factor. The hope is that CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) and higher ranked professionals take pay cuts before passing them down to lower wage employees.

The Korean and Chinese pandemic experience highlights differential effects of layoffs across sectors. Essential services such as medical services, utilities, logistics, ICT (information and communications technology) services, banking, public administration and defense, and essential goods production such as agriculture, power, and medical equipment have remained functional. Some other goods and services have adaptable production processes, which can transition to online delivery, such as educational services. These sectors would be able to tide through with some short-term investments in technology and skilling. The remaining sectors such as mining, some manufacturing sub-sectors (such as clothing, automobile, and furniture, to name a few), construction, personal services, and trade would be adversely affected in the short to long run. Control of the coronavirus pandemic requires minimum human contact, hence the demand as well as supply of these goods and services would be low. This implies that workers whether regular/salaried or casual or self-employed would have different experiences depending on the sector in which they are engaged in.

In short, the pandemic will have severe effects on vulnerable groups. In this time, we should not let go of our humanity, and ensure that policies are addressed towards alleviating further suffering.

A version of this piece has appeared on The Wire: https://thewire.in/political-economy/coronavirus-pandemic-how-to-mitigate-the-lockdown-impact-on-vulnerable-populations

Notes:

- This is different from the number of total migrants in India, which is 450 million, as quoted in the media. However, not all migrants migrate for the purposes of work. For example, about 210 million migrated due to marriage. We, therefore, focus on only those migrants who report “work or employment” as their reason for migration in our figure from Census 2011. We refer to them as migrant workers.

- We classify migrant workers in a district as temporary if they moved to the place of enumeration from their previous residence less than a year ago.

- We use PLFS survey data for this because the Census does not contain information about daily-wage workers.

- We do not show district-level variations in the figure because the numbers are calculated using data from a survey and not the census. Therefore, the estimates of the proportion at the district level come with relatively high degree of sampling uncertainty. The state-level estimates are more stable in that regard.

- Estimates based on NSSO’s (National Sample Survey Office) 2011-12 Employment and Unemployment Survey, as quoted in ILO’s (International Labour Organization) India Wage Report (2018).

Further Reading

- Dasgupta, Aparajita (2017), "Can the major public works policy buffer negative shocks in early childhood? Evidence from Andhra Pradesh, India", Economic Development and Cultural Change 65, no. 4: 767-804.

- Deshpande, A and R Ramachandran (2020), ‘Which Indian Children are Short and Why? Social Identity, Childhood Malnutrition and Cognitive Outcomes’, Ashoka Economics Discussion Paper Series.

- International Labour Organization (2018), ‘India Wage Report: Wage policies for decent work and inclusive growth’, ILO Decent Work Team for South Asia and Country Office for India.

- Nandi, A, S Mazumdar, and JR Behrman (2018), “The effect of natural disaster on fertility, birth spacing, and child sex ratio: evidence from a major earthquake in India”, J Popul Econ 31, 267–293 (2018).

03 April, 2020

03 April, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.