One-third of all seats in village councils are reserved for women. The government has proposed an increase in quota to 50%, and in the period of reservation from five to 10 years. Based on a survey conducted in Maharashtra, this column finds that availability of basic public services for women is better in female-headed villages - when the female head has been in the job for 3-3.5 years.

In 1993, India took an important step towards deepening democracy when it passed the 73rd Amendment that put in place the Gram Panchayat (GP) (elected village council) at the village level. An important feature of this Amendment was reservation for women in GP seats and sarpanch (elected head of GP) posts. This was indeed a crucial step considering the low status of women in India and their consequent low participation in public life. But what have been the impacts and implications of this policy? The anecdotal evidence in this context is mixed. While, on the one hand, it has been claimed that quite often, women sarpanchs are just a front for the male relatives; on the other hand, it has been argued that female sarpanchs are indeed proactive and bring about several positive changes in the village.

Female sarpanchs and service availability in villages

In this column, we put forth some answers based on our research (Sathe et al. 2013). The purpose of our study was to examine if the reservation for women for the post of sarpanch has had any significant impact on the perceived availability of basic public services for women in the villages, especially with respect to the services that women are believed to value the most. It is the responsibility of the GP to provide basic public services such as clean drinking water, toilets, gutters etc. to the villagers. Thus the well-being of the villagers depends, to a great extent, on the efficacy of the GP. It is also expected that sarpanchs would play a crucial role in the provision of these services, by their initiative and interest. Further, we also examine if the political participation of women in villages varies depending on the gender of the sarpanch.

The implications of mandatory reservation for women in GPs are well-researched. Following the work by Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004), several other studies have analysed the issue. However, the focus of these studies has been on the investments made by the GPs in various services like roads, sanitation etc. It is highly plausible that even if money is spent on a public service, there are leakages (via corruption) in the system, which may impact the availability of the services provided in terms of quantity and quality. This aspect has not been captured.

Banerjee and Dulfo (2011) sum it well when they state that “…studies elsewhere in India have made it clear that women leaders almost always make a difference.” The need now is to examine the channels through which reservation policy operates, and whether the resulting ‘difference’ is positive or negative.

The survey

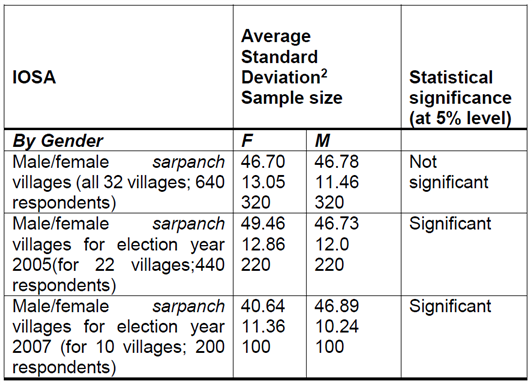

We conducted a survey of the intended beneficiaries to understand what kind of services they perceived they have access to. Using an appropriate sampling strategy, we selected 16 villages with a female sarpanch and 16 with a male sarpanch, in the Sangli district of Maharashtra. The state reserved 33% of GP seats and sarpanch posts in 1994. The survey was conducted in October-November 2008. From each of these villages we randomly selected 20 female villagers and so, on the whole, we had a sample of 640 respondents1. We developed an ‘Index of Services Availability’ (IOSA), which captures the quality and quantity of services that are available to the women respondents living in the 32 villages. The survey focussed on services and issues that are of particular relevance to women: (i) Drinking water; (ii) Toilets; (iii) Gutters; (iv) Schools; (v) Ration shops; (vi) Self-help groups; (vii) Implementation of welfare schemes, with special reference to Nirmal Gram Yojana (cleanliness scheme) and Janani Suraksha Yojana (maternal health scheme); and (viii) Male Alcoholism. Thus, although roads and electricity help women as well, we have not included them in this Index.

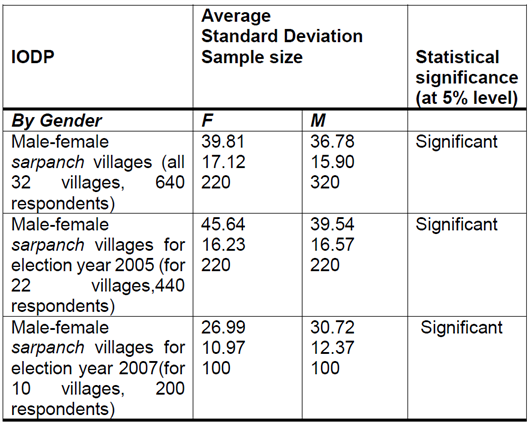

To analyse the impact of the gender of the sarpanch on political participation of female villagers, we asked questions with respect to voting patterns, knowledge about the responsibilities and workings of the GP, attendance and vociferousness in the gram sabhas (local public meetings), and political awareness. Based on these factors, we estimate the ‘Index of Democratic Participation’.

Findings

We found that the male sarpanchs were somewhat superior in terms of socioeconomic and educational status and had better political connections vis-à-vis the female sarpanchs. In spite of this, female sarpanchs seemed to have had interesting and important impacts.

The availability of basic public services was found to be significantly higher in female-sarpanch villages as compared to male-sarpanch villages, in cases where the election had been held 3-3.5 years prior to the survey. However, this result is not obtained when the election had been held one year before the survey. This suggests that female sarpanchs become more effective relative to male sarpanchs over a period of time.

Table 1. Comparison of Index of Services Availability (IOSA) across female sarpanch and male sarpanch villages

Table 2. Comparison of Index of Democratic Participation (IODP) across female sarpanch and male sarpanch villages

What this means for policy

The policy implication that comes out of this is that mandated reservation for women in sarpanch posts would work better if the tenure is increased from five years to (say) 10 years. This would be more effective than increasing the reservation for women to 50%, as has been done in April 2011 by the Government of Maharashtra.

Notes:

- We also interviewed the 32 sarpanchs, insights from which are in Sathe et al. (2013).

- Standard Deviation (SD) is a measure that is used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values.

Further Reading

- Banerjee, A and E Duflo (2011), Poor Economics: Rethinking Poverty and the Ways to End It, Random House India.

- Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra and Esther Dulfo (2004), “The Impact of Reservation in Panchayati Raj: Evidence from a Nationwide Randomized Experiment”, Economic and Political Weekly, 39(9):979-86.

- Sathe, Dhanmanjiri, Stephan Klasen, Jan Priebe and Mithila Biniwale (2013), “Can the Female Sarpanch Deliver? Evidence from Maharashtra”, Economic and Political Weekly, 48(11):50-57.

23 October, 2016

23 October, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.