In this note, Abinash Dash Choudhury – who works as part of a network of researchers to present fortnightly data on the humanitarian crisis associated with Covid-19 in India – writes about the current state of the traditional fortune-tellers of South Odisha. Used to wandering about in villages and towns to earn their living before the lockdown, this tribe has been jolted by the full-scale restriction on their movement due to the lockdown, which has proved detrimental for their income sources.

“Our incomes are heavily contingent on the place we are at. People drop a rupee coin sometimes, for reading their palms. Sometimes, when the news seems happy to them, they drop a 10-rupee note! Our fates are tied to theirs,” Wadaskar chuckles after saying this, his sense of humour still alive. He and his kinsmen are stuck in Koraput district’s Baipariguda block, for the last three months since the lockdown began. Koraput district in South Odisha is one of India’s most vulnerable districts1. Hunger, destitution, poverty, and precarity of lives have been a historical fact here.

Wadaskar, who lives with about a hundred others of his troop, are traditional fortune-tellers who live a banjara life – wandering about in villages and towns, settling for a while before making the next move. They have spent their childhood years learning this skill from their parents, as a kulvidya, which they will pass on to the next generation. For years, they have lived on this knowledge, and the little money that it yields, after intense waiting and travelling. On average, they earn around Rs. 200 per family each day, making it difficult to make ends meet.

“Home? It has been long since there has been a home for us, like you or someone else we see around here. It was about two decades ago that we, the 15 families, set out to leave our village in Nagpur, Maharashtra. It was the place we belonged to...however, long ago, about two decades before we left, our parents had started to venture out, too. I was born in Jagdalpur (which now falls within the borders of the Chhattisgarh state). Our people have come to Baipariguda since early 2000s and have kept moving around South Odisha. Village after village, we are on the road year-round, sans the monsoon”, narrates Gyanachi Wadaskar, on a telephonic call.

Lockdown crippled our lives…

On 24 March, when the first phase of lockdown was kick-started without any warrant or caution, Wadaskar – along with nearly a 100 others including about 32 young children between the age of 5-10 – were caught off-guard. Such a full-scale restriction on their movement was detrimental to their income sources, and jolted them, for their way of living was suddenly transformed. “We did not know where to go, what to do, and how to survive! It was impossible to think that we could see the light of day in the next seven days, then...”, he exclaims. However, civil society interventions, along with local support helped Wadaskar and his neighbours sustain themselves with immense difficulty. “We were given cooked meal once a day, and dry rations for some days – it was a nightmare to have lived through. We had put up tents to stay and continued living there throughout”, he adds.

Gyanachi Wadaskar and his neighbours could somehow live through the first few phases of the lockdown because of those small-scale interventions and the proactive measures taken by the Government of Odisha. The government had begun community kitchen services in every panchayat (village council), to make cooked food available to the vulnerable population. The state government’s notification made it clear that each panchayat had to identify about 100-200 vulnerable individuals, and necessary care of such persons were to be taken by the local administration through the assistance of the block officials. It is due to this service, along with local care networks, the likes of Gyanachi, had survived.

In the last few weeks, as there has been mounting pressure on the state for taking care of migrant workers reaching their home districts, and with the focus being on quarantine centres, all cooking-related activities are now centralised at these centres. “Those days are gone, though. It has been weeks since we received any such food. The gradual reduction of lockdown, or whatever this means, has also meant we are increasingly left on our own now. We have not received any food from anyone since the second week of May, and have had to fend for ourselves. This month has come to be the most difficult for us. Where will we get our money from? Who will take care of us now? What do we do?”, Wadaskar asks, confused and scared.

The desertion of vulnerable groups in villages across various blocks has come across as a serious lapse on the part of a state government that has otherwise been constantly vigilant towards the needs of its citizens.

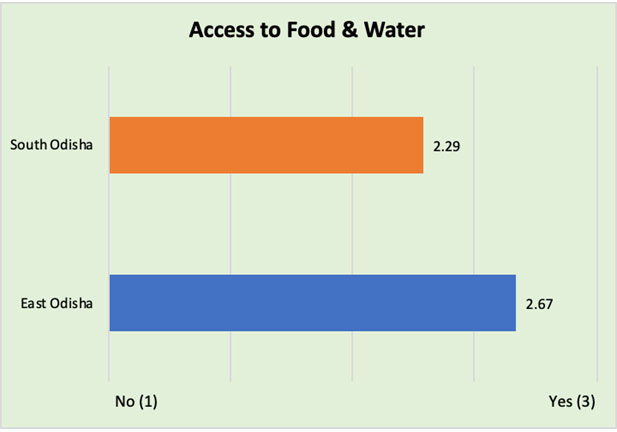

As per the findings of the India - Covid Assessment and Response Dashboard (I-CARD)2 survey for May, access to food has been relatively lower in the blocks of South Odisha3 (including Baipariguda of Koraput district) as compared to the blocks of East Odisha4 (Figure 1). On a scale of 1 to 3, South Odisha has relatively lower access to food and water (score of 2.29) as compared to East Odisha (score of 2.67).

Figure 1. Access to food and water in Odisha

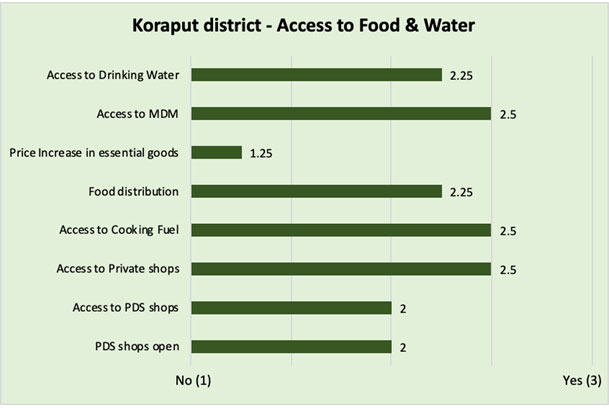

Further, when I-CARD looked at different issues related to food and water in the surveyed blocks of Koraput district, it found out that access to PDS (public distribution system) shops, drinking water, and food distribution (by government/non-government organisations/individuals) to vulnerable groups5 require immediate attention (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Access to food and water in Koraput district

Our block expert from Baipariguda said that after the announcement of lockdown, ration for three months was distributed to people from different hamlets. The ration shops remain open, to provide ration to those who still have not received it. However, in many villages, the shops are far away – about 8-10 kilometres from the hamlets. Hence, it is difficult to access the ration shops easily. To improve access, government has made revenue villages as the nodal centres for ration delivery.

Further, as mentioned above, community-kitchen services by the government and food distribution by NGOs (non-governmental organisatios) happened initially for a month (in April), but does not happen anymore with the same intensity. Thus, many vulnerable families, including those of nomadic fortune-tellers like Gyanachi, are struggling to get two meals a day.

Income loss, Statelessness, and forced labour

The precarious situation of Gyanachi and his neighbours, is not limited only to the availability of cooked meals. With no other way to earn, and with no footfall in the market areas, Gyanachi and his troop have lost their incomes since the last three months.

Substantiating this, the survey findings of I-CARD show that there has been a significant loss of income amongst craft workers, self-employed, and non-agricultural daily-wage labourers. On a scale of 1 to 3 – with 1 indicating low and 3 indicating high – the income losses for such workers in South Odisha, and particularly Koraput district and Baipariguda block, are high with a score of 3 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Income loss of daily-wage labourers, self-employed, and skilled craft workers in South Odisha

According to our block expert from Baipariguda, craft workers and artisans, including bamboo workers and potters, are distressed without any sale. Amongst the self-employed, poultry farms are affected, and many small shop-owners are forced to shut their shops as they have no working capital. Daily-wage labourers too have lost their jobs.

The fortune-tellers, who have lost their traditional livelihood, live a life of non-citizens in nowhere-land. Without any valid identity card – a ration card or a job card – they have no claim to the basic services in the area. “We have not had any benefit. Who will give us anything to save us? In one night, we are forced to become construction labourers – a job we have never done! We are lifting bricks as a private contractor pays us some money to do the job. We shall sleep hungry if we do not do that job. We turned into labourers overnight!”, Gyanachi exclaims.

Loss of traditional livelihood, hunger, and relentless uncertainty has rendered the fortune-teller community helpless, and has taken away their choice of occupation.

At crossroads

In the throes of desperate, unprecedented uncertainty in their lives, most like Gyanachi and his neighbours, are solely dependent on the basic services of the state.

A multi-faceted, target-oriented approach ensuring the continuation of community kitchens, universalisation of PDS services, and employment generation or immediate unemployment wages for those who cannot indulge in extensive labour, or cannot adapt to shift to manual labour, shall go a long way in rehabilitating some sense of normalcy to these lives.

It is difficult to ascertain if they can ever go back to where they were before the long lockdown began. For Gyanachi and his kins, lives changed in the blink of an eye. “An invisible disease and a forlorn life – all that we had is gone now! Where is our home? Where do we go? What will be for us? Ab toh bhagwan jaane. Humara qismat hum hi nahin jaane ab toh!”, laments Gyanachi, trying to imply that he really does not know his fortune anymore, and will never know anyone else’s too.

Notes:

- Koraput district has over 50% tribal population (Census 2011) and is one of the 115 aspirational districts listed by the NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog.

- I-CARD is an independent project of a network of researchers, in collaboration with over 100 Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), to present fortnightly data on the Covid-19 humanitarian crisis for vulnerable groups. This project is supported by Azim Premji University.

- Surveyed blocks of South Odisha include Gosani, Gumma, and Rayagada of Gajapati district; Dharakote, Jagannathpur, and Khallikote of Ganjam district; Jayapatna, Kokasara, and Lanjigarh of Kalahandi district; Bandhugaon, Baipariguda, Borigumma, and Kundura of Koraput district; Jharigam, Nayagarh, and Muniguda of Nabrangpur, Nayagarh, and Rayagada districts respectively.

- Surveyed blocks of East Odisha include Danagadi, Dharmasala, and Jajapur blocks of Jajapur district; Champua, Joda, Kendujhar Sadar, and Patana of Kendujhar district; and Joshipur and Thakurmunda blocks of Mayurbhanj district.

- Vulnerable groups here refers to the most economically distressed groups: https://www.i-card.org/dashboard

30 June, 2020

30 June, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.