The ruling Trinamool Congress has emerged victorious in the recent Assembly elections in the state of West Bengal. Using electoral data from 2016, 2019, and 2021, Ghatak and Maitra analyse the change in vote shares of the contesting parties – the relative balance of pro- and anti-incumbency forces at work, aspects of gender and religious polarisation, as well as the impact of the Covid-19 surge.

As the dust settles on the electoral outcome of the 2021 Assembly elections in the state of West Bengal, and some consensus emerges as to what drove its salient patterns, a few important questions deserve a more in-depth analysis.

The ruling TMC (Trinamool Congress) bucked an anti-incumbency headwind to register an increase in vote share, from 45% in 2016 to 48% in 2021 as well as in the number of seats, from 211 to 213. The results of the 2019 national parliamentary (Lok Sabha) elections had established the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) as the main opposition party in the state. The BJP has maintained that position with its vote share going up from 10.5% in 2016 to 38% in 2021, and the number of seats from 3 to 77. The Left Alliance got 9% of the total votes, with its major constituents, the CPI (M) (Communist Party of India (Marxist)) and the INC (Indian National Congress) winning 4.7% and 2.9% of the votes, respectively. It won only one seat, which was by the newly formed ISF (Indian Secular Front).

There have been both pro- and anti-incumbency waves at work in this election. Some of the TMC’s 209 (excluding the two seats where elections have been postponed) seats from 2016 went to the BJP (48). At the same time, some of the Left’s and the INC’s seats went to the TMC (23 and 29, respectively), while the rest went to the BJP (9 and 15, respectively). In Table 1, we present the implications of the change in vote shares on the change in the distribution of seats between 2016 and 2021. The TMC has held on to the 76.5% of the seats it won in 2016, and also gained considerably from a change in allegiance from those who voted for the others in 2016: it captured 72% of the seats that the Left Front won in 2016 and 66% of the seats won by INC in 2016. A striking observation from our analysis is the extent to which the TMC – not the BJP – benefited from the vote shares of the Left Front and the INC. This is contrary to the popular commentary that the rise of BJP as a political power in West Bengal has been driven by the movement of the Left voters to the BJP as a result of their antipathy to the ruling disposition after being under their rule for a decade.

Table 1. Change in winning party: 2016 and 2021

|

Total Seats in 2016 |

Left |

BJP |

TMC |

INC |

Other |

IND |

|

|

Left |

32 |

0 |

9 |

23 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

(0.00) |

(28.12) |

(71.88) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

||

|

BJP |

3 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

(0.00) |

(66.67) |

(33.33) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

||

|

TMC |

209 |

0 |

48 |

160 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

(0.00) |

(22.97) |

(76.56) |

(0.00) |

(0.48) |

(0.00) |

||

|

INC |

44 |

0 |

15 |

29 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

(0.00) |

(34.09) |

(65.91) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

||

|

Other |

3 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

(0.00) |

(66.67) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(33.33) |

(0.00) |

||

|

IND |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

(0.00) |

(100.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

||

|

Total Seats in 2021 |

292 |

0 |

77 |

213 |

0 |

2 |

Source: Authors’ computation using data published by the Election Commission of India.

Notes: (i) Sample restricted to the 292 constituencies (out of the 294 assembly constituencies) where elections were conducted in 2021. (ii) In the table, IND stands for independent candidate. (iii) Figures in parentheses refer to the percentage of the number of seats won in the 2016 state Assembly elections.

Voting: Gender patterns and religious polarisation

What drives this shift in party-specific votes? One leading hypothesis is the gender pattern of voting, with women voting for TMC due to its various pro-poor transfer schemes like Kanyashree as well as the perception of a female leader taking on male national political leaders the tone of whose campaign sometimes did grate on gender-sensitivities of Bengali voters cutting across party lines. The Lokniti-CSDS (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies) post-poll survey results do indicate a 13 percentage point gender advantage to the TMC, and this was particularly pronounced among poorer women.

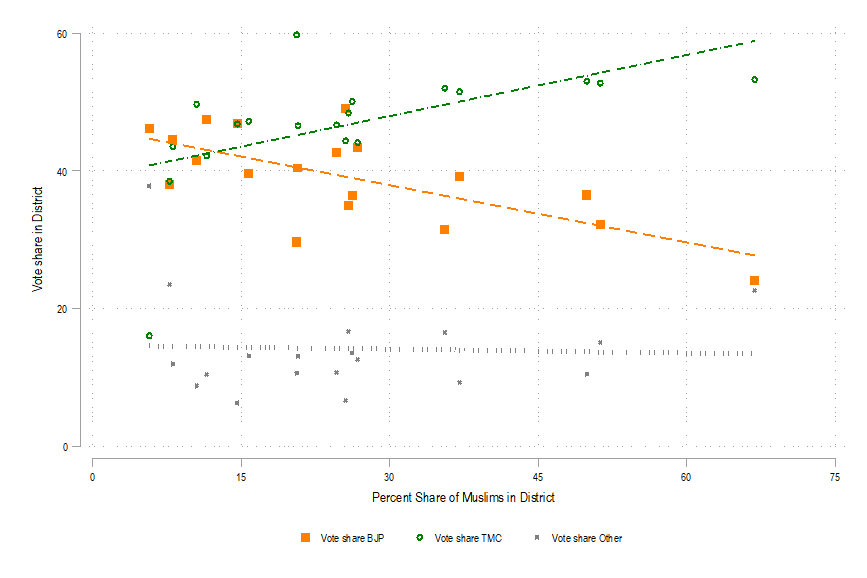

The other hypothesis is the consolidation of minority votes who decided that the TMC was the best bet against the BJP, over the Left Alliance. In the set of strategies that the BJP tried out in this election, religious polarisation was very much in the mix and was played out with much more enthusiasm that any other election in recent memory. In Figure 1 we present the correlation between the percentage share of Muslims in the district as per the 2011 Census and the average vote share of TMC and BJP in the district. Clearly the share of Muslims in the district is positively correlated with the vote share of TMC and negatively correlated with the vote share of BJP. Interestingly, the vote share of the other parties (including the Left Alliance that included ISF) is not correlated with the share of Muslims in the district, remaining constant at about 18%.

Figure 1. Proportion of Muslims in district and vote shares of BJP, TMC, and other parties

Source: Authors’ computation using data published by the Election Commission of India.

Notes: (i) Sample restricted to the 292 constituencies (out of the 294 assembly constituencies) where elections were conducted in 2021. (ii) Population share of Muslims in the district obtained from the 2011 Census. (iii) Districts as of 2011. (iv) Lines denote the fitted values.

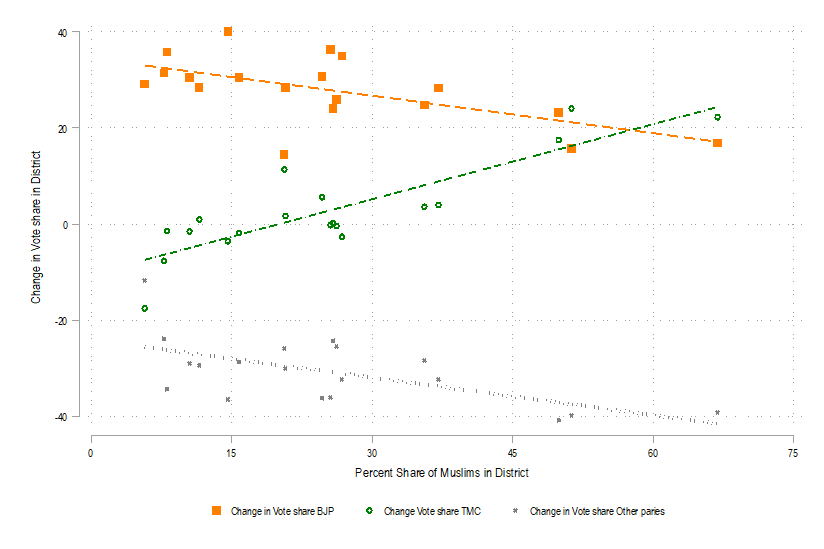

The effect of religious polarisation is borne out when we examine the correlation between the change in vote share of the different parties between 2016 and 2021 and the share of Muslims in the district. An increase in the share of Muslims in the district is positively correlated with the change in the vote share of TMC over the period, but negatively correlated with the change in the vote share of BJP and other parties. Notably, in districts with a low Muslim share in the population, TMC’s vote share actually decreased and the BJP’s vote share increased substantially. It is likely that the minority population viewed the TMC as a safe option that would support them against the BJP and its majoritarian policies. This was more salient in districts with a greater share of Muslims. This is consistent with the Lokniti-CSDS’s post-poll survey results that show that the vote of Muslims for the TMC went up from 51% to 75% – a massive swing.

Figure 2. Proportion of Muslims in district and change in vote shares of BJP, TMC, and other parties

Source: Authors’ computation using data published by the Election Commission of India.

Notes: (i) Sample restricted to the 292 constituencies (out of the 294 assembly constituencies) where elections were conducted in 2021. (ii) Population share of Muslims in the District obtained from the 2011 Census. (iii) Districts as of 2011. (iv) Lines denote the fitted values.

Covid-19 impact?

We now turn to a factor that has not been discussed much at all. The 2021 elections were held across eight phases, spread over a month. Importantly, though the elections were held under the shadow of a surge in Covid-19 cases in West Bengal: over this period, the number of Covid-19 cases and deaths in West Bengal increased exponentially. Prime Minister Narendra Modi was criticised for holding large election rallies in support of the local BJP candidates, where masks were not compulsory. Did the rising infections have an effect on the voting pattern and the election outcomes?

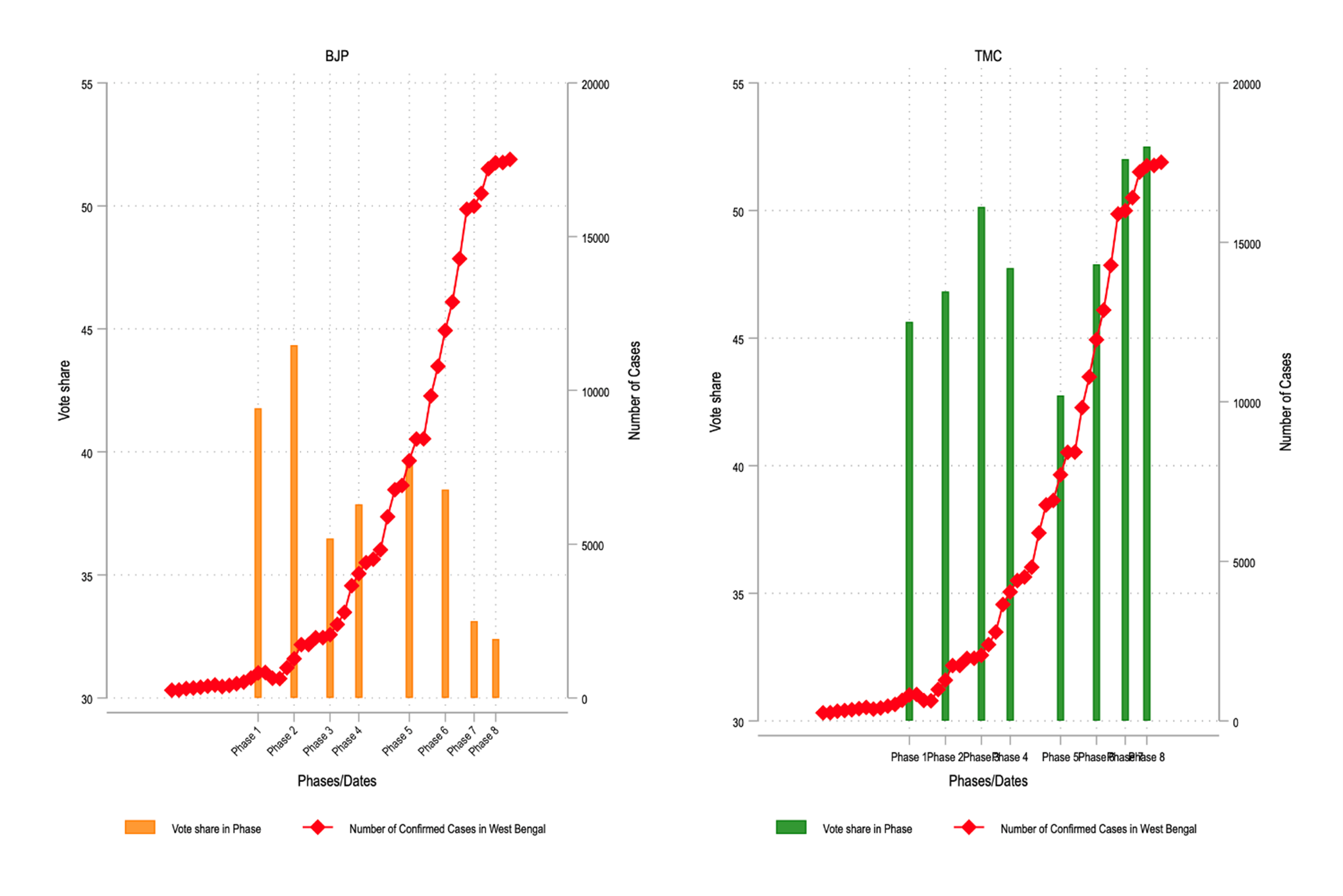

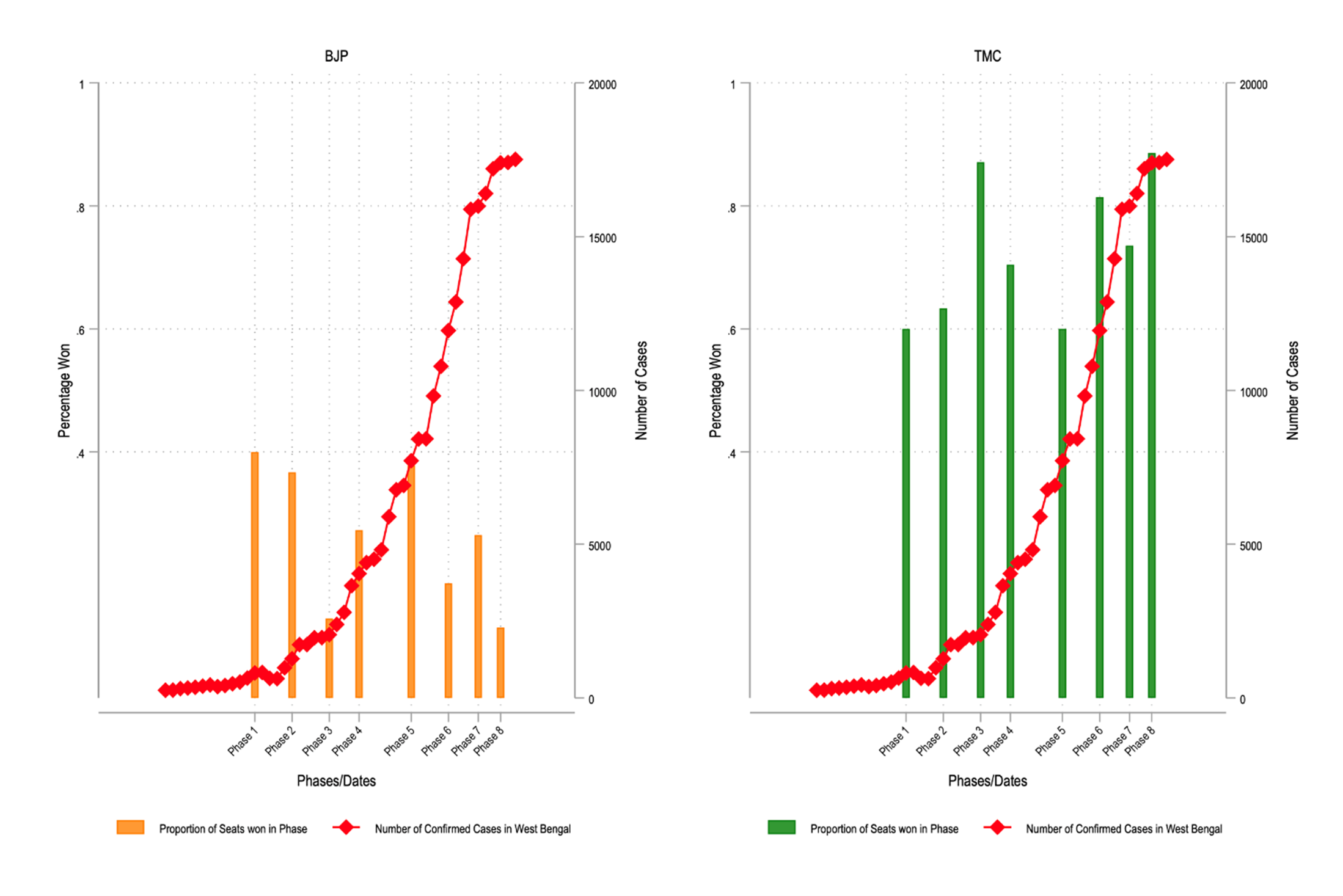

Figure 3 presents the vote shares of TMC and BJP across the different phases, and Figure 4 shows the likelihood of TMC and BJP winning across the different phases.1 The figures also depict the reported number of daily cases over the relevant period. During this period, the daily reported number of cases in West Bengal increased from around 100 per day (mid-March) to more than 15,000 a day (early May). In the latter phases, the vote share of and the likelihood of BJP winning falls, while the vote share of and the likelihood of TMC winning increases.

The figures suggest that for TMC, both the vote shares and the likelihood of winning seats increased in the latter phases, while for BJP, both vote shares and the likelihood of winning fell in the corresponding phases.

Figure 3. Effect of Covid-19 and vote shares of BJP and TMC, by phases

Source: Authors’ computation using data published by the Election Commission of India, and reported number of cases of Covid-19 (https://api.covid19india.org/documentation/csv/.

Figure 4. Effect of Covid-19 on proportion of seats won by BJP and TMC, by phases

To better understand the effect of the surge in Covid-19 on election outcomes we can make two sets of comparisons. We define the constituencies where the elections were conducted in Phases 6, 7, and 8 as the surge constituencies. First, we compare the outcomes between outcomes in the 2016 and 2021 Assembly elections in the surge constituencies and the non-surge ones. Second, we do the same comparison but take the assembly components of the 2019 parliamentary election instead.2 We conduct the two sets of comparisons, because in 2016, the BJP won only three seats and about 10.5% of the votes and therefore, the 2019 numbers are more informative.

We find that relative to 2016, the surge in 2021 reduces the vote share of the BJP and other parties (including the ISF alliance) by 7.24 and 4 percentage points respectively, and increases the vote share of TMC by 11.05 percentage points. Relative to 2019, the surge in 2021 has no effect on the vote share of BJP, and reduces the likelihood of victory for BJP by almost 12 percentage points. On the other hand, the surge increases the vote share of TMC by almost 8 percentage points and the likelihood of TMC winning by 20 percentage points. The increase in vote share of TMC is matched by a similar decline of vote share of the other parties. We interpret the results as follows – the surge affected the election outcomes not so much by negatively affecting the vote shares and likelihood of victory for BJP, but rather by positively affecting the electoral outcomes (vote shares and likelihood of victory) for TMC at the cost of the vote shares (and ultimately the likelihood of victory) of the other parties. This reinforces our earlier observation – the TMC benefited from the collapse of the vote share of the Left Front and the INC, and this seems to have been particularly pronounced in the later stages with the surge in Covid-19 cases.

The Lokniti-CSDS post-poll analysis is consistent with this. They find that 24% of voters decided who they are going to vote for at the very last minute or a day or two before voting day, and among such voters, it was the TMC and not the BJP that did extremely well. Not only that, this margin of late-deciding voters going for the TMC as opposed to the BJP – while present in all phases – went up noticeably after Phase 5 of the elections (that is, during the surge period). While 47% of voters in the first five phases decided at the last minute and at the time of campaigning, the corresponding proportion in the last three phases was 52%.

Concluding remarks

For over 34 years, West Bengal was a bastion of the Left, and appeared to be a permanent feature of the political landscape of the state. This changed in 2011 when the TMC came to power in an anti-incumbency wave and was re-elected comfortably in 2016. However, in this election they were battling anti-incumbency headwinds with widespread allegations of corruption, misgovernance, and political repression along partisan lines. The BJP smelled an opportunity to ride this to come to power, after their successful performance in the 2019 parliamentary elections. A triangular electoral contest throws up many uncertainties and one of the most surprising aspects of the final outcome was the migration of votes from the Left Alliance to the ruling TMC. Not only have the majority of the Left Alliance seats in 2016 moved to TMC in 2021, the gain in TMC votes during the Covid-19 surge period came at the cost of Left Alliance votes and not – as expected – of BJP votes.

While much has been said about TMC’s ability to stand up to the BJP juggernaut, the fact that a large part of the electoral success has come at the cost of the Left Alliance has gone virtually unnoticed. Our analysis enables a better understanding of the dynamics of voting and electoral competition in West Bengal. John F Kennedy is supposed to have said that “victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan”. The TMC has clearly emerged victorious in this election; but the BJP has not lost – after all it had only three seats in 2016 and now it has 77 and it has massively consolidated its position as the main opposition party. However, if one uses the expectation and buzz that was generated during the campaign as a benchmark, partly reflected in the opinion polls, it has clearly lost with respect to that. If one were to do a counterfactual exercise and think about the one thing that they could have easily changed, the BJP would have been clearly better off not stretching the election for such a long period, as was done in the in states of Tamil Nadu (one phase, despite having a much larger area) and Assam (three phases) which also had state Assembly elections around the same time in 2021. Not only would it have helped check the rise in Covid-19 cases, evidence suggests that it would have helped the BJP secure more votes. In business as in politics, sometimes doing the right thing is also beneficial from the point of more narrow self-interest.

Notes:

- As the assignment of seats to phases was not systematic, we can – with reasonable confidence – claim that this approach gives us an unbiased estimate of this factor.

- The assembly components of the parliamentary elections refer to the assembly constituencies that make up the parliamentary constituencies. For example, the Kolkata Dakshin parliamentary constituency consists of the following assembly constituencies: Kolkata Port, Bhabanipur, Rashbehari and Ballygunge. The Election Commission publishes data on the party-wise distribution of votes for each assembly constituency associated with each parliamentary constituency.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

12 May, 2021

12 May, 2021

By: swaraj chakrabarti 24 July, 2021

I liked your in depth analysis especially from the perspective of Covid 19. However, I would have liked to see what other factors you considered that went in favor of TMC. Surprisingly, I see no comment on this article. No wonder nowadays people don't comment on in depth analysis but on shallow and frivolous issues.