The Mandal Commission and Sachar Committee reports, among others, have indicated the existence of caste inequalities within the four major caste groups. However, data on this subject remain limited. Using data from a novel 2014-2015 survey conducted in Uttar Pradesh, this article shows that within-group inequalities among upper castes are significantly less, relative to the within-group inequalities observed among both Hindu and Muslim OBCs and Dalits.

Broadly, four social groups – Hindu upper castes, Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs) or Dalits, Scheduled Tribes (STs) – are used for administrative and governance purposes by the government under Articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution of India (Government of India 1956, Lamba and Subramanian 2020). In 1950, the Constitution granted reservations in employment and education for SCs and STs to overcome caste barriers in socioeconomic status. These reservations were extended to OBCs in the 1990s after the recommendations of the Mandal Commission (Fontaine and Yamada 2014). However, till date, no reservations have been awarded to minority religious groups, like Muslims. While the origins of the caste system come from the Varna system1 described in Vedic literature – foundational texts of the Hindu religion – over time, this social evil has also been assimilated or has diffused into other religions (Ahmad 1967). A significant number of lower-caste Hindus converted to Islam and Christianity to escape the caste rigidity of Hindu society (Ahmad 1967, Trofimov 2007). The Sachar Committee Report on the Social, Economic, and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India in November 2006 was an important landmark in this regard (Sachar et al. 2006). The report provided comprehensive evidence on Muslim backwardness in several indicators using data from the 2001 Census of India and other official statistics from central and state government reports. Recent studies have identified and documented empirical evidence on caste‐based untouchability in Muslims and occupational segregation across six socio-religious groups2 (Kumar et al. 2020, Trivedi et al. 2016a, Trivedi et al. 2016b).

Even within the four major caste groups (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras) of Hindu society, there has been a growing demand for reservation by various politically and economically dominant castes across India (for example, Marathas in Maharashtra, Patidars in Gujarat, Jats in north India, Kapus in Andhra Pradesh) and this has become a burning issue for the political classes of the country (Deshpande and Ramachandran 2017). However, there is limited evidence to resolve the demand for economic class‐based quotas for dominant OBCs and upper castes. The absence of a caste census and the lack of unit‐level data on multidimensional developmental indicators such as education, employment, income, wealth, and household amenities at different sub‐caste levels, act as a barrier to rationalise these influential castes’ growing demand for quotas.

In a recent study (Tiwari et al. 2022), we provide empirical evidence for assessing the multidimensional relative deprivation of different sub‐castes in terms of poverty, wealth, and financial inclusion in the Uttar Pradesh – the largest populated state of India, where caste‐based discrimination and dominance are deep‐rooted (Kumar et al. 2020, Trivedi et al. 2016a, 2016b). Our study contributes to the emerging literature (Anderson et al. 2015) on resurgent identity politics and mounting disquiets of social and economic development of marginalised communities within the broad socio-religious groups in India.

Our study

We use data from a unique primary survey collected by the Giri Institute of Development Studies (GIDS) during 2014-2015 to assess the social and educational status of OBCs and Dalit Muslims in Uttar Pradesh. The survey, for the first time, identifies sub-castes within broad socio-religious groups in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Previous studies using this survey strongly suggest that Dalit Muslims – who are not only engaged in the same occupations as Hindu Dalits but are also poorer than their counterparts and unable to avail of the government’s affirmative action benefits – need to be taken into consideration when formulating related policy (Kumar et al. 2020, Trivedi et al. 2016a, 2016b).

Complementing previous research, in this study, we provide sub-caste-wise inequalities within broad socio-religious groups across five broad socio-economic domains: deprivation of lifestyle, historical deprivation, household conditions, wealth accumulation, and financial inclusion.

Deprivation in lifestyle: Poverty and expenditure

In Table 1, we present mean monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) and poverty levels for both Hindus and Muslims across sub‐castes. Our findings suggest enormous disparities in MPCE and poverty levels by caste, in both rural and urban areas. In rural areas, the average MPCE of ‘Hindu General’ (henceforth, upper-caste Hindus) and Jats (OBCs) is higher than all other castes, for both Hindus and Muslims. However, the average MPCE of Jats, Brahmins, and Thakurs is more than two times higher than Dalits, regardless of religion. The average MPCE of ‘Other Hindu General (Non-Brahmins and Non-Thakurs)’ is also much higher than non-Jat OBCs and Dalits, regardless of religion. It is noteworthy that Jats in Uttar Pradesh who are categorised as OBCs – have the highest MPCE, even higher than Brahmins and Thakurs. Lodhs, Paasi, and Other Hindu Dalits (excluding Chamars) have the lowest MPCE relative to other castes in the sample. In urban areas, the general economic dominance of Hindus is even more evident, while Jats fall back and are at a similar level as other Hindu OBCs, while Muslims are worse off in urban areas.

Table 1. Mean monthly per capita consumption expenditure and poverty headcount ratio, by caste

|

Caste |

Rural |

Urban |

||||||

|

Mean MPCE |

Rural poverty |

Share in population |

Share in MPCE |

Mean MPCE |

Urban poverty |

Share in population |

Share in MPCE |

|

|

Brahmins |

1,688 |

15.9 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

2,302 |

4.9 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

|

Thakur/Kshatriya |

1,677 |

9 |

0.05 |

0.08 |

2,440 |

7.3 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

|

Other Hindu General |

1,546 |

20.6 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

2,362 |

2 |

0.08 |

0.14 |

|

Hindu General |

1,659 |

14.4 |

0.15 |

0.23 |

2,346 |

3.9 |

0.17 |

0.29 |

|

Muslim General |

1,278 |

31.3 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

1,529 |

25 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

|

Yadavs |

1,128 |

32.1 |

0.07 |

0.06 |

1,399 |

29.6 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

|

Kurmis |

1,003 |

40.7 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

1,998 |

13.9 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

|

Jats |

1,956 |

15.3 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

1,779 |

14.6 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

Lodhs |

743 |

61.3 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

1,217 |

43.9 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

|

Other Hindus OBCs |

1,060 |

42.3 |

0.2 |

0.19 |

1,236 |

35.4 |

0.19 |

0.15 |

|

Hindu OBCs |

1,150 |

38 |

0.34 |

0.34 |

1,342 |

32.7 |

0.29 |

0.26 |

|

Ansari Muslims |

1,039 |

39.4 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

1,195 |

44.5 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

|

Other Muslims OBCs |

994 |

37.7 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

1,176 |

36.6 |

0.1 |

0.07 |

|

Muslim OBCs |

1,008 |

38.2 |

0.17 |

0.14 |

1,186 |

40.4 |

0.2 |

0.15 |

|

Chamars |

931 |

48 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

1,207 |

44.4 |

0.1 |

0.09 |

|

Paasi |

759 |

56.3 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

1,116 |

37.5 |

0.004 |

0.003 |

|

Other Hindu Dalits |

775 |

61.8 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

1,163 |

37.8 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

|

Hindu Dalits |

879 |

51.9 |

0.18 |

0.15 |

1,191 |

42.3 |

0.16 |

0.13 |

|

Dalit Muslims |

853 |

52.5 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

1,058 |

48.4 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

|

All Hindus |

1,190 |

36.8 |

0.63 |

0.56 |

1,569 |

27.4 |

0.56 |

0.63 |

|

All Muslims |

1,046 |

39.2 |

0.23 |

0.25 |

1,237 |

38.6 |

0.29 |

0.24 |

|

NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) 68th Round (2012) |

30.4 |

26.1 |

||||||

Caste-wise disparities in poverty levels are more unsettling. The percentage of the population below the poverty line ranges from just 9% in Thakurs to as high as 61% in Lodhs and other Hindu Dalits in rural areas. More than 50% of Dalits in the sample, among both Hindus and Muslims, are below the poverty line, while the same is just 20% or less for upper-caste Hindus and Jats. Poverty gaps become even more pronounced in urban areas where there Dalit Muslims experience 24 times more poverty (48%) compared to Thakurs, who have the lowest poverty level (2%). All upper-caste Hindus have less than 10% poverty, while excluding Jats and Kurmis, all OBC castes have 30% and all Dalits castes have above 40% of the population below the poverty line in both religions.

However, consumption in states like Uttar Pradesh is not solely driven by income but has a strong association with region-specific consumption habits such as expenditures on marriages and other socio-cultural and religious ceremonies beyond their capacity (Ojha 2007). Therefore, we also examine economic inequalities by castes through other socio-economic indicators.

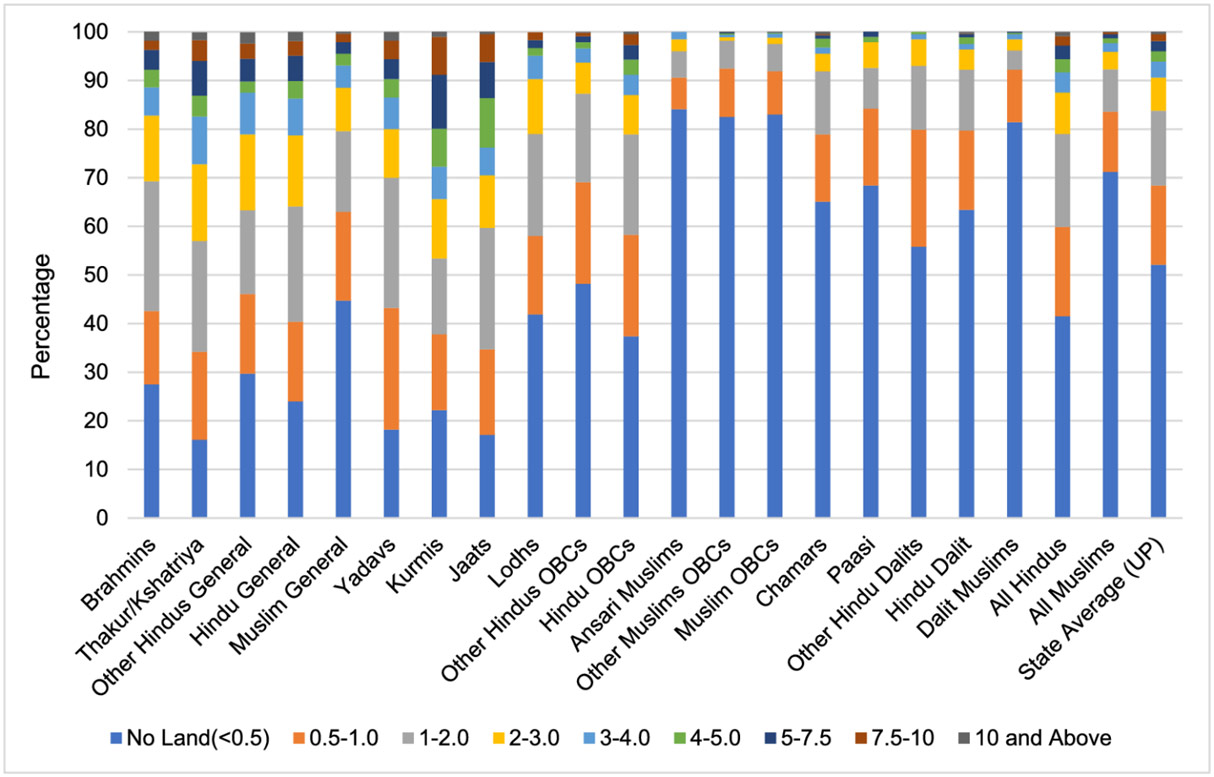

Historical deprivation: Land ownership

The social distribution of land plays a key role in the economic and social development of rural and agrarian economies like Uttar Pradesh. The ownership of cultivable land by sub‐caste shows substantial disparity (Figure 1). The most commonly landless households are Muslim OBCs and Dalit Muslims, followed by Paasi and Chamars from among Hindu Dalits. While upper-caste Hindus account for 20% of the sampled households, they own more than 30% of the total cultivable land. The intra‐caste distribution of land shows alarming disparities. Some castes disproportionately own more land relative to their share in population. For instance, the share of land owned by Thakurs is 11% followed by Brahmins (15%), Other Hindu castes (6%), Yadavs (13%), Kurmis (4%), and Jats (8%). However, the corresponding estimated population shares of the aforementioned sub-castes are 7%, 10%, 4%, 10%, 3%, and 5%, respectively.

Figure 1. Cultivable land ownership (in acres), by caste

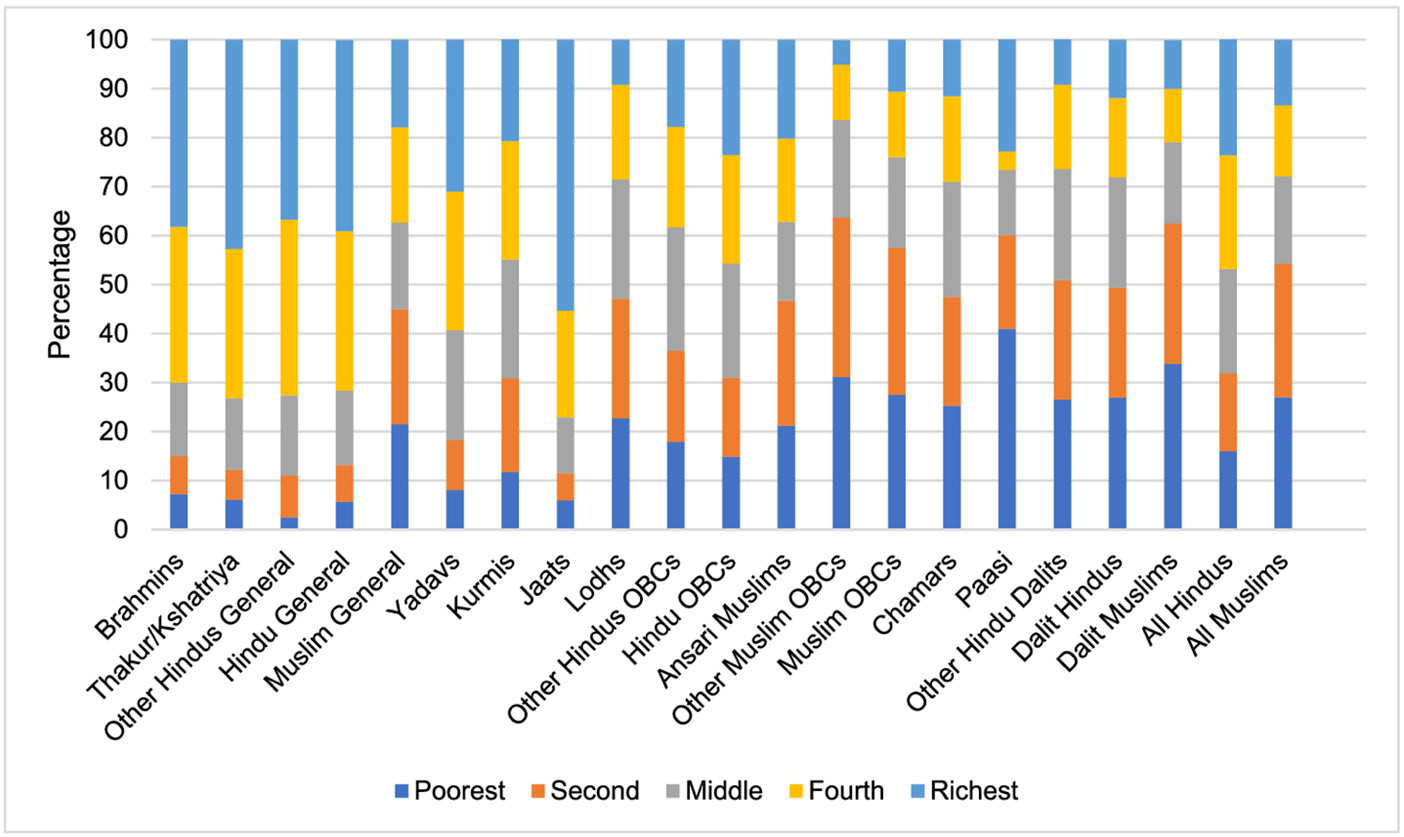

Deprivation in wealth accumulation

To further scrutinise economic disparities across castes, we also examined the household wealth status among the different sub‐caste groups using self‐reported asset value information (excluding agricultural land). We find that a significantly higher proportion of Jats (55%), Thakurs (43%), Brahmins (38%), Other Hindu General (37%), and Yadavs (31%) belong to the richest wealth quintile (Figure 2). On the other hand, about 40% of households of Paasi, Chamaars, and Lodhs belong to the poorest wealth quintile.

Figure 2. The economic status of households, by caste

Financial exclusion: Sources of loans

We assess financial exclusion through the exclusion of lower castes from formal banking services. Table 3 shows sources of loans by sub-caste groups. We find that an individual’s caste plays a pivotal role in determining the sources of loans from formal banking services. Lower caste individuals mostly get loans from friends, relatives, and local moneylenders, while Hindu upper castes disproportionally access loans through formal banking services. Exclusion from formal financial services forces lower castes to depend primarily on informal financial sources for borrowing – which makes them vulnerable to debt traps by moneylenders and further perpetuates the vicious cycle of poverty.

Table 3. Main sources of loan, by caste

|

Caste |

Banks (including co-operative banks) |

Co-operative credit society |

Registered moneylenders |

Kisan Credit Card |

Friends/ |

Other money lenders and others |

|

Brahmins |

27.4 |

2.4 |

0.8 |

41.9 |

20.2 |

7.3 |

|

Thakur/Kshatriya |

31.7 |

2.5 |

0 |

51.7 |

6.7 |

7.5 |

|

Other Hindus General |

43.7 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

28.2 |

21.1 |

4.2 |

|

Hindu General |

32.7 |

2.2 |

0.6 |

42.5 |

15.2 |

6.7 |

|

Muslim General |

18.9 |

2 |

2.5 |

15.9 |

46.8 |

13.9 |

|

Yadavs |

23.3 |

6.7 |

0 |

28.3 |

28.3 |

13.3 |

|

Kurmis |

16.7 |

4.2 |

2.1 |

27.1 |

47.9 |

2.1 |

|

Jaats |

15.9 |

4.6 |

0 |

69.3 |

6.8 |

3.4 |

|

Lodhs |

2.6 |

0 |

23.1 |

12.8 |

38.5 |

23.1 |

|

Other Hindus OBCs |

15.4 |

1.2 |

2 |

24.9 |

33.3 |

23.2 |

|

Hindu OBCs |

16.2 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

30.5 |

30.4 |

17.6 |

|

Ansari Muslims |

9.3 |

0 |

0.7 |

5 |

67.9 |

17.1 |

|

Other Muslims OBCs |

7.2 |

1.1 |

9.4 |

3.4 |

44.5 |

34 |

|

Muslim OBCs |

7.9 |

0.7 |

6.4 |

4 |

52.6 |

28.2 |

|

Chamars |

15.3 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

22.1 |

39.1 |

20.4 |

|

Paasi |

25.9 |

0 |

0 |

7.4 |

48.2 |

18.5 |

|

Other Hindu Dalits |

11.1 |

1.6 |

0 |

9.5 |

57.1 |

20.6 |

|

Hindu Dalits |

15.4 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

19 |

42.7 |

20.3 |

|

Dalit Muslims |

9.6 |

0 |

1.5 |

6.1 |

56.6 |

26.3 |

|

All Hindus |

19.6 |

2.2 |

1.8 |

29.6 |

30.8 |

16.1 |

|

All Muslims |

11.5 |

1 |

4.1 |

8.9 |

50.9 |

23.6 |

Policy implications

We find that the persisting between-caste hierarchy and significant within‐caste inequality plays a pivotal role in shaping poverty and other economic deprivation in the state. Upper-caste Hindus and Muslims are much better off than their lower caste counterparts. Within-group inequalities among upper castes are significantly less compared to the within-group inequalities observed among both Hindu and Muslim OBCs and Dalits. Nevertheless, the within-group hierarchy has not been adequately addressed in existing government policies. Although, the Rohini commission was constituted in 2017 to study the growing demand for sub-categorisation of OBCs into extremely backward and more backward classes, its report is still awaited. The Supreme Court too recently reopened the debate on the sub-categorisation of SCs and STs for reservations. State governments and the central government should take appropriate steps to ensure the reduction of between- as well as the within-group inequality, so that the most deprived, within the disadvantaged groups are not left further behind.

The existence of caste among Muslims has still not received wider acceptance in academia and is also not recognised by the State. On account of this, vulnerable Dalit Muslims, who are equally or more deprived than Hindu Dalits, miss out on accessing the affirmative action policies. There is also a lack of data at the all-India level to support the argument of the existence of caste among Muslims, and the deprivation faced by OBCs and Dalit Muslims. What we observe in Uttar Pradesh could also be true for the rest of India. However, lack of data, specifically a caste census prevent researchers from making similar assessments for the population of the rest of India. Thus, a caste census is critical to design policies to ensure the socioeconomic welfare of all social groups in India.

Notes:

- The caste system comprises four hierarchical groups, or varnas – the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. Certain population groups – known today as Dalits – were historically excluded from the varna system and were regarded as untouchables, and within each varna, and among the Dalits, are hundreds of castes or jatis. (Munshi 2019).

- The six socio-religious groups are Hindu General (upper-caste Hindus), Muslims General (upper-caste Muslims), Hindu OBCs, Muslim OBCs, Hindu Dalits, and Dalit Muslims (Kumar et al. 2020, Trivedi et al. 2016a, Trivedi et al. 2016b).

Further Reading

- Ahmad, Imtiaz (1967), “The Ashraf and Ajlaf categories in Indo-Muslim society”, Economic and Political Weekly, 2(19): 887-891.

- Anderson, Siwan, Patrick Francois and Ashok Kotwal (2015), “Clientelism in Indian villages”, American Economic Review, 105(6): 1780-1816.

- Deshpande, Ashwini and Rajesh Ramachandran (2017), “Dominant or backward? Political economy of demand for quotas by Jats, Patels, and Marathas”, Economic and Political Weekly, 52(19): 81-92.

- Government of India (1956), ‘Constitution of India’.

- Lamba, Rohit and Arvind Subramanian (2020), “Dynamism with incommensurate development: The distinctive Indian model”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(1): 3-30.

- Fontaine, Xavier and Katsunori Yamada (2014), “Caste comparisons in India: Evidence from subjective well-being data”, World Development, 64: 407-419.

- Kumar, S, F Prashan, K Trivedi and S Goli (2020), Backward and Dalit Muslims: Education, employment and poverty, Rawat Publications.

- Munshi, Kaivan (2019), “Caste and the Indian Economy”, Journal of Economic Literature, 57(4): 781-834.

- Ojha, RK (2007), “Poverty dynamics in rural Uttar Pradesh”, Economic and Political Weekly, 42(16).

- Sachar, R, S Hamid, TK Oommen, MA Basith, R Basant, A Majeed and A Shariff (2006), “Social, economic, and educational status of the Muslim community of India: Sachar Committee Report, 2006”, Contemporary Education Dialogue, 4(2): 266-71.

- Tiwari, Chhavi, Srinivas Goli, Mohammad Zahid Siddiqui and Pradeep S Salve (2022), “Poverty, wealth inequality, and financial inclusion among castes in Hindu and Muslim communities in Uttar Pradesh, India”, Journal of International Development, 1-29 (published online).

- Trivedi, Prashant K, Srinivas Goli, Fahimuddin and Surinder Kumar (2016a), “Does untouchability exist among Muslims?”, Economic and Political Weekly, 51(15): 33-36.

- Trivedi, Prashant K, Srinivas Goli, Fahimuddin and Surinder Kumar (2016b), “Identity equations and electoral politics: Investigating Political Economy of Land, Employment and Education”, Economic and Political Weekly, 51(53): 117-123.

- Trofimov, Yaroslav (2007), ‘In India, 'Untouchables' Convert To Christianity -- and Face Extra Bias’, The Wall Street Journal, 19 September.

20 April, 2022

20 April, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.