This article identifies and attempts to fill the gaps in understanding the effects of reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) in panchayats. Using data from a state-wide census, multiple administrative datasets, and primary survey data from Bihar, it finds that reservations reduce asset inequality between SCs and others. It investigates the mechanisms through which this takes place – including greater targeting of public goods, access to welfare programmes, and improved political participation. In this context, they also show that reservation works best when sub-castes within SCs are few and their population in the panchayat is neither too small nor too large.

Countries worldwide have implemented a number of affirmative action policies to reduce inter-group disparities. For instance, in the context of India, political reservation policies aim to provide adequate representation to historically underprivileged minority groups in government positions. The underlying assumption is that this representation will lead to social and economic empowerment and, consequently, reduce overall inequality.

While several studies have attempted to document the effects of reservations in favour of minority groups (Pande 2003, Duflo 2005), some gaps in the literature remain. We identify four broad gaps: first, not much is known about the impacts on wealth and asset accumulation; second, the effects of reservations across different jatis, or sub-castes, is an important question that is still under-studied; third, the extent to which reservation’s effects vary in the short- and long-run, especially at the local level, is also under-explored1; finally, a crucial gap is the relationship between the size and diversity of a minority group and the impact of reservations.

Utilising a natural experiment in Bihar

To address these questions, we take advantage of a natural experiment in Bihar, where reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) were introduced for Gram Panchayat (GP) head positions. As per the Bihar Panchayati Raj Act (2006), nearly 17% of GP head positions across the state were reserved for SCs. GPs are selected for the implementation of reservation based on their SC populations – within each block (of roughly 15 GPs), GPs with SC populations above a certain threshold almost certainly have positions reserved for SCs. By comparing villages that narrowly missed the threshold for reservation with those just above it, we employ a fuzzy regression discontinuity design to causally measure the impact of caste-based reservations on both SCs and non-SCs, the various jatis within these broad groupings, and map out the distributional effects across households and villages.

Results

Bihar implemented reservations for a 10-year cycle. A GP once reserved in 2006 for SCs, would be reserved similarly even in the 2011 elections, and would only switch its status in the 2016 polls. We utilise a wealth of data sources from 2006 -2019, including private asset data of over 19 million households from the socio-economic caste census (SECC), and a primary survey of 8,748 households to measure impacts in the long run.

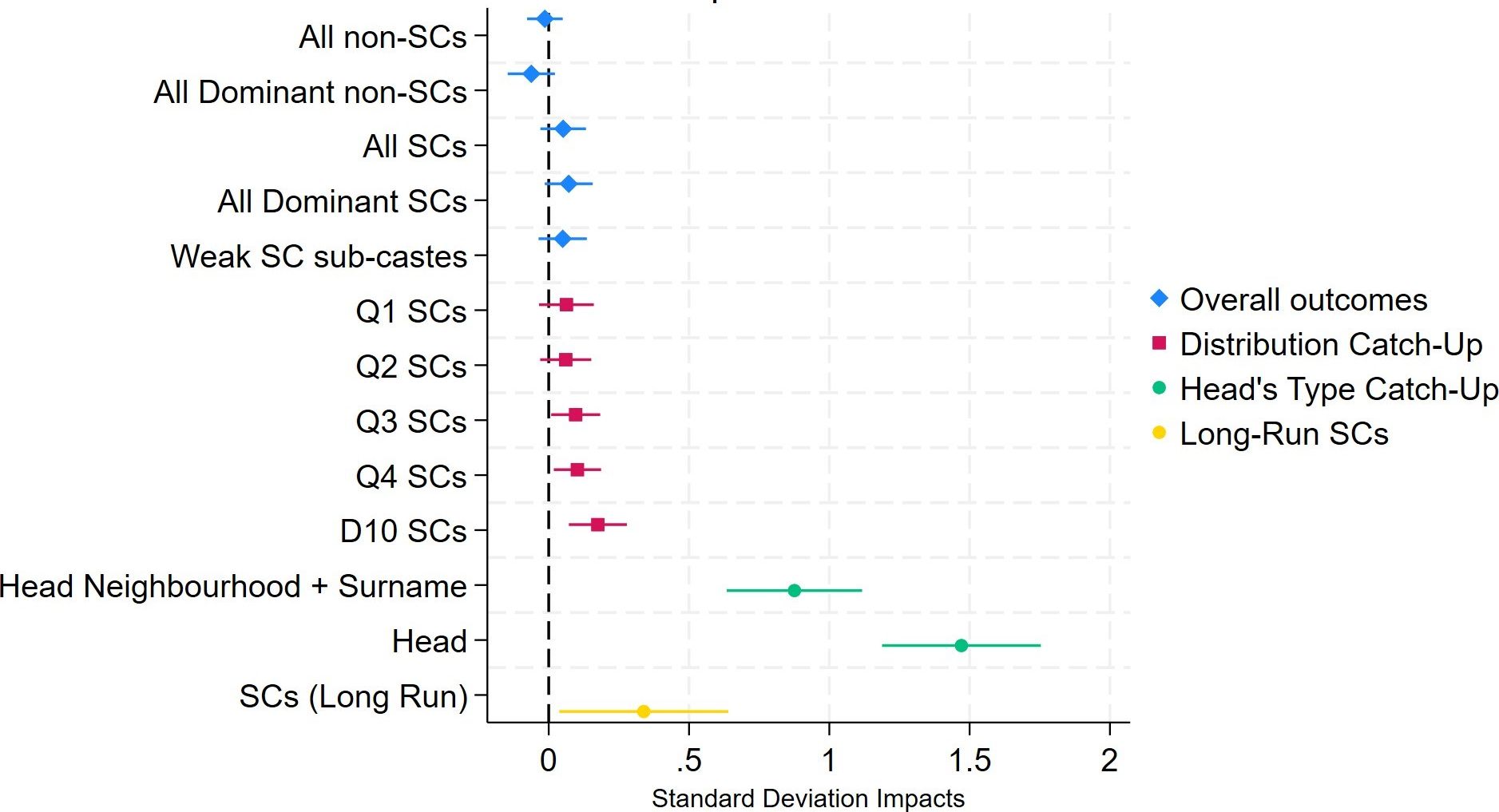

Our findings reveal that SC reservations reduce private asset inequality between SCs and non-SCs, with modest effects in the short run, but substantive impact in the long run (See Figure 1). This reduction is driven partly by an increase in mean SC asset scores and a decrease in non-SC asset scores. We find no evidence of an equity-efficiency tradeoff: that is, the average asset ownership among all households in the GP is unaffected by reservation. Since SC leaders help minority households without reducing the average wealth across all households, improvements in equity do not come at the cost of inefficient governance.

Figure 1. Distributional impacts of reservation for SCs

Notes: i) This figure shows impacts on asset scores across various sub-populations in terms of standard deviations. ii) The blue diamond markers pertain to absolute scores. iii) The red square markers delineate catch-up with the median non-SC quintile. Each marker looks at a different SC quartile – for instance, “Q1 SCs” indicates difference between the average SC in the bottom quartile and the average non-SC in the median quintile. iv) The green circular markers also delineate catch-up with the median non-SC quintile. However, in the reserved group, we only focus on individuals connected with the village head: “head neighbourhood + surname” includes everyone within a 20-household distance from the head who also shares the head’s surname, while “head” includes only the head’s household. v) The yellow markers indicate the long-run impacts on SCs from our primary survey. vi) 90% confidence intervals are included.

In the short run, within the SC group, reservations have varied effects, with the third and fourth quartiles of the asset distribution in reserved areas being (statistically) significantly better off than their counterparts in unreserved areas. This indicates a slight increase in inequality within the SC group. However, the numerically dominant sub-caste within SCs does not benefit more than the average SC household, and Mahadalits, the weakest SC sub-castes, are not differentially affected by reservations.

Who benefits then? In line with the literature on elite capture (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2000, Besley et al. 2012), we also show that those closer to the elected village head, either due to sharing the same surname or living in proximity, experience greater benefits. We also find that the real gains of reservation on asset accumulation accrue to SCs in the long run. Our primary survey of GPs sampled from around the reservation threshold shows that SCs catch up substantially with non-SCs. Crucially, these results are seen after the reservation cycle was switched.

Mechanisms through which reservations have distributional impacts

How could reservation affect SC asset ownership? In the short run, it is likely to be affected mainly through better-targeted welfare schemes as a result of greater representation. But, in the long run, reservation could influence wealth accumulation through a few additional channels. First, asset ownership of SCs can change in response to improved access to village-level public goods. Second, if wealth gains made during the period of reservation allow poor SCs to escape poverty traps, households could be pushed into a path of wealth accumulation. Material gains could also be sustained in the long run if reservation caused greater political participation and empowerment of SCs.

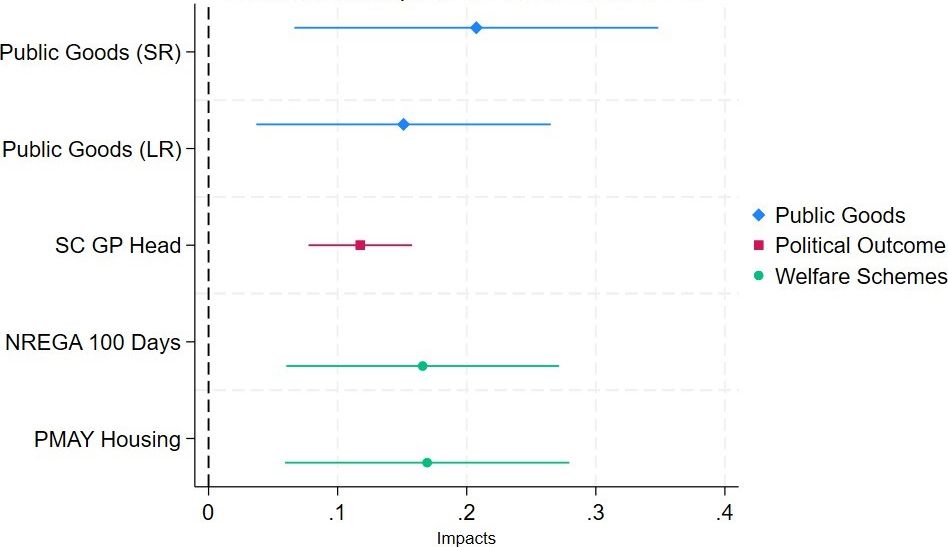

We investigate these mechanisms and summarise our results in Figure 2. We find greater targeting of welfare programmes towards SC households in reserved GPs. The share of SC households receiving work under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and houses under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana scheme also improves.

Figure 2. Social and political impacts of reservation for SCs

Note: The five outcomes measured are: (i) standardised impacts on public goods in the short run (Census, 2011), (ii) standardised long-run impacts in administrative data on village lanes and drains projects from 2016-2018 (sourced from the Department of Panchayati Raj), (iii) impacts on the probability of SCs becoming GP heads (in the 2016 GP elections), (iv) PMAY houses built per SC individual from 2016-2019), and (v) normalised share of SC households getting 100 days under the NREGA scheme (2014-2015)

Since the impact of reservations on private assets is relatively small in the short run, escaping poverty traps is unlikely to explain the substantial gains in the long run. However, consistent with Besley et al (2004), we find that key public goods are better targeted towards SC hamlets. We focus on 4 main public goods: government primary schools, roads, Anganwadi centres, and ration shops. The population normalised share with access to these public goods increases by 0.2 SD in reserved GPs. Interestingly, here too, we find no equity-efficiency trade-off: the average amount of public goods in the GP is unaffected by reservation.

We also find strong evidence in favour of the political participation channel: reservation in earlier years empowers SCs to win GP elections even in the absence of reservation in later elections. Formerly reserved places see a five-fold increase in the share of SC GPs when compared to similar but never-reserved GPs. We also find greater participation of SCs at the lower-tiered ward elections, both in their ability to contest and win elections. These results all point to the emergence of a new political class among SCs in GPs that see reservations for a ten-year period.

Heterogeneity by size and diversity

We delve into how the impact of reservations varies based on the size and diversity of the SC population. We find that reservations work best when SCs are neither too small nor too large in number in constituencies. When SCs are too few, reservations bring material gains and access to public goods in the short run but may not lead to long-term political power, which is crucial to sustaining gains. When SCs are many, reservations are not needed to bring additional material gains, since their sheer numbers make them an important enough political constituency even in unreserved areas. However, when SCs have a moderate composition, reservations offer benefits in the short run, while their size ensures political representation even in the absence of reservations. We also examine the impact of ethnic diversity within SCs, using sub-caste variation as a proxy. We find that reservations are most effective when SCs are homogeneous. This finding is related to the larger literature on ethnic differences and public good provision (see Alesina et al. (1999), Banerjee and Pande (2007), and Das et al. (2017)).

Policy implications

This paper has a few policy implications: first, it indicates that reservation works better when it is frozen over two cycles (in line with the findings of Beaman et al. (2009), Bardhan et al. (2010), Deininger et al. (2015)), since the gains seem to accrue to the SCs only in the long run. Second, it shows that well-implemented reservation policies could be self-reinforcing: reservation creates material wealth for minorities which allows them to participate in elections even in the absence of reservations, which in turn helps them accumulate more wealth. Third, since the size and diversity of the minority group matter for where reservation works best, reservations at the local level could work better in states where the share of SCs is neither too large nor too small.

Note:

- Some papers examining short-run effects are Besley et al. (2004), Duflo et al. (2005), Dunning and Nilekani (2013), and Das et al. (2017). For long-run effects at higher-state levels, see: Pande (2003), Chin and Prakash (2011), Jensenius (2015), and Gulzar et al. (2020).

Further Reading:

- Alesina, Alberto, Reza Baqir and William Easterly (1999), “Public goods and ethnic divisions”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4): 1243-1284.

- Banerjee, AV and R Pande (2007), ‘Parochial politics: Ethnic preferences and politician corruption’, Working Paper.

- Bardhan, Pranab, Dilip Mookherjee and Monica Parra Torrado (2010), “Impact of Political Reservations in West Bengal Local Governments on Anti-Poverty Targeting”, Journal of Globalization and Development, 1. Available here.

- Beaman, Lori, Raghabendra Chattopadhyay, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande and Petia Topalova (2009), “Powerful Women: Does Exposure Reduce Bias?”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4): 1497-1540.

- Besley, Tim, Rohini Pande, Lupin Rahman and Vijayendra Rao (2004), “The Politics of Public Good Provision: Evidence from Indian Local Governments”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 2(2-3): 416-426.

- Chin, Aimee and Nishith Prakash (2011), “The redistributive effects of political reservation for minorities: Evidence from India”, Journal of Development Economics, 96(2): 265-277.

- Das, S, A Mukhopadhyay and R Saroy (2017), ‘Efficiency consequences of affirmative action in politics: Evidence from India’, Working Paper.

- Deininger, Klaus, Songqing Jin, Hari K. Nagarajan and Fang Xia (2015), “Does Female Reservation Affect Long-Term Political Outcomes? Evidence from Rural India”, The Journal of Development Studies, 51(1): 32-49.

- Duflo, Esther (2005), “Why Political Reservations?”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2-3): 668-678.

- Duflo, E, G Fischer and R Chattopadhyay (2005), ‘Efficiency and rent seeking in local government: Evidence from randomized policy experiments in India’, J-PAL Working Paper.

- Dunning, Thad and Janhavi Nilekani (2013), “Ethnic Quotas and Political Mobilization: Caste, Parties, and Distribution in Indian Village Councils”, American Political Science Review, 107(1): 35-56.

- Gulzar, Saad, Nicholas Haas and Benjamin Pasquale (2020), “Does Political Affirmative Action Work, and for Whom? Theory and Evidence on India’s Scheduled Areas”, American Political Science Review, 114(4): 1230-1246.

- Jensenius, Francesca Refsum (2015), “Development from Representation? A Study of Quotas for the Scheduled Castes in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(3): 196-220.

- Pande, Rohini (2003), “Can Mandated Political Representation Increase Policy Influence for Disadvantaged Minorities? Theory and Evidence from India”, American Economic Review, 93(4): 1132-1151.

28 November, 2023

28 November, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.