Emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have achieved a remarkable decline in inflation since the early 1970s. Whether EMDEs can continue enjoying the benefits of low inflation will depend on the confluence of structural and policy-related factors that have fostered global disinflation over the past decades being sustained. Against this backdrop, this article analyses the factors supporting disinflation in EMDEs, and whether EMDEs can sustain low inflation.

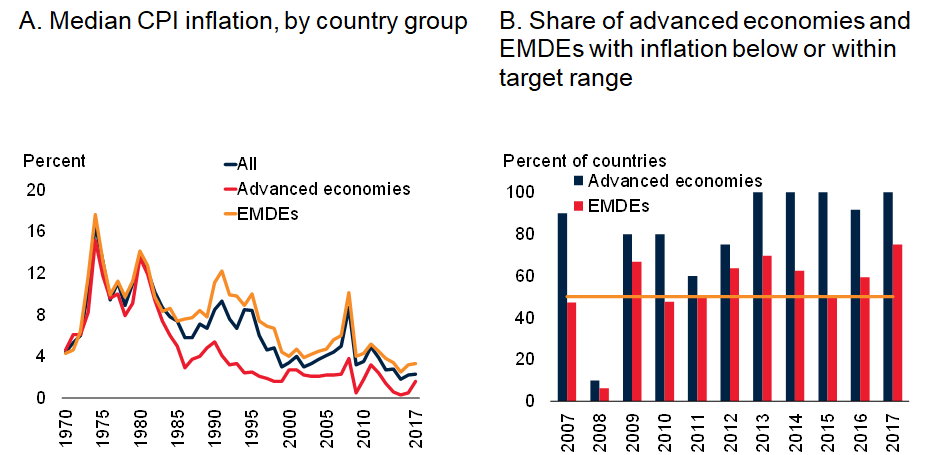

Emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have achieved a remarkable decline in inflation since the mid-1970s (Ha, Kose, and Ohnsorge 2019). Median annual national consumer price inflation (CPI) in EMDEs fell from stubbornly persistent double-digits during the 1970s to about 3% in 2018 (Figure 1). By 2017, inflation was within or below central bank target ranges in three-quarters of the EMDEs that had adopted inflation targeting. Inflation has also fallen around the world, from a peak of 17% in 1974 to around 2.5% in 2018. The substantial decline in inflation began in the mid-1980s in advanced economies and in the mid-1990s in EMDEs. By 2000, global inflation had stabilised at historically low levels.

Low and stable inflation has historically been associated with greater output stability, higher growth, and better development outcomes. Whether EMDEs can continue enjoying the benefits of low inflation will depend on the confluence of structural and policy-related factors that have fostered global disinflation over the past decades being sustained. Against this backdrop, this article addresses the following questions:

- What have been factors supporting disinflation in EMDEs?

- Can EMDEs sustain low inflation?

Figure 1. Global inflation

Sources: Bloomberg, Consensus Economics, Haver Analytics, IMF (International Monetary Fund) International Financial Statistics, and World Economic Outlook databases; OECDstat, World Bank.

Notes:

- Median year-on-year CPI for 29 advanced economies and 123 EMDEs (including 28 low-income countries).

- All inflation rates refer to year-on-year inflation. Share of 11 advanced economies and 24 EMDEs with CPI below-target or within target range. Horizontal line indicates 50%.

What have been main factors supporting disinflation in EMDEs?

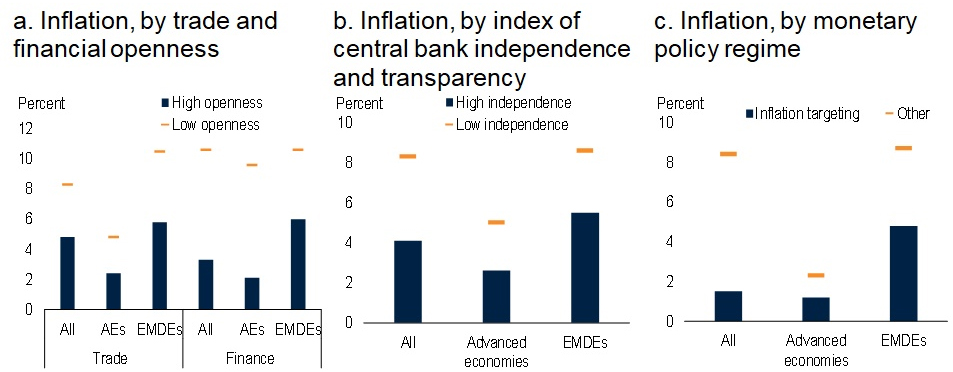

While the global financial crisis played a major role in pushing inflation down around the world over the past decade, the longer-term trend of disinflation has been supported by a wide range of structural forces. The most significant of these have been the widespread adoption of more effective and transparent monetary, exchange rate, and fiscal policy frameworks as well as globalisation (Figure 2).

- Macroeconomic policies: In the second half of the 1980s and during the 1990s, many EMDEs implemented macroeconomic stabilisation programmes and structural reforms, and gave their central banks clear mandates to control inflation. The adoption of resilient policy frameworks has facilitated more effective control of inflation (Taylor 2014, Fischer 2015). Inflation tends to be lower in countries that employ an inflation targeting framework and that have more independent and transparent central banks. Changes in fiscal policy frameworks have also contributed: fiscal rules have been adopted in 88 countries, including 49 EMDEs. Other reforms, including labour market and product market liberalisation, also assisted the disinflation process.

- Trade and financial integration: Over the past five decades, global trade openness has risen by more than half, contributing to lower prices through competitive pressures from foreign producers or through global value chains that transmit global disinflationary cost shocks (Auer, Levchenko, and Sauré 2017). Financial integration has helped discipline macroeconomic policies since more financially integrated economies are likely to implement monetary policies targeting low and stable inflation (Kose et al. 2010). Inflation tends to be lower in economies that are more open to trade and financial flows.

Figure 2. Factors associated with disinflation

Sources: Ha, Kose, and Ohnsorge (2019); Haver Analytics; IMF International Financial Statistics and World Economic Outlook databases; OECDstat; World Bank.

Notes:

- Columns indicate median inflation in countries with high trade-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratios (‘Trade’) or financial assets and liabilities relative to GDP (‘Finance’) in the top quartile (‘high openness’) of 175 economies during 1970-2017. Horizontal bars indicate countries in the bottom quartile (‘low openness’). Differences are statistically significant at the 5% level.

- B.C. Columns indicate median inflation in country-year pairs with a central bank independence and transparency index in the top quartile of the sample (B) or with inflation targeting monetary policy regimes (C). Horizontal bars denote medians in the bottom quartile (B) or with monetary policy regimes that are not inflation targeting (C). Differences are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Can EMDEs sustain low inflation?

The achievement of low inflation cannot be taken for granted (Rogoff 2003, 2014; Draghi 2016; Carstens 2018). If cyclical and structural forces become less disinflationary over the next decade than they have been over the past five decades, inflation could rise globally. Structural and policy-related factors that have helped lower inflation over the past several decades may lose momentum or be rolled back amid mounting populist sentiment.

- Slowing globalisation: The rising protectionist sentiment of recent years may slow or even reverse the pace of globalisation. New tariffs and import restrictions have been put in place in advanced economies and EMDEs since 2017. The possibility of further escalation in trade restrictions involving major economies remains elevated.

- Weakening monetary policy frameworks: A shift from a strong mandate of price stability, to objectives related to the financing of government, would undermine the credibility of monetary policy frameworks and raise inflation expectations. Among EMDEs, a decline in central bank independence and transparency has been associated with significantly less well-anchored inflation expectations and greater pass-through of exchange rate movements to inflation.

- Weakening fiscal policy frameworks: Growing populist sentiment could lead to a move away from rule-based fiscal policies. Fiscal rules can become ineffective once commitment to them falters. Mounting public and private debt in EMDEs could also weaken commitment to strong fiscal and monetary policy frameworks. Government and/or private sector debt has risen in more than half of EMDEs since 2012, including in many low-income countries (World Bank, 2018).

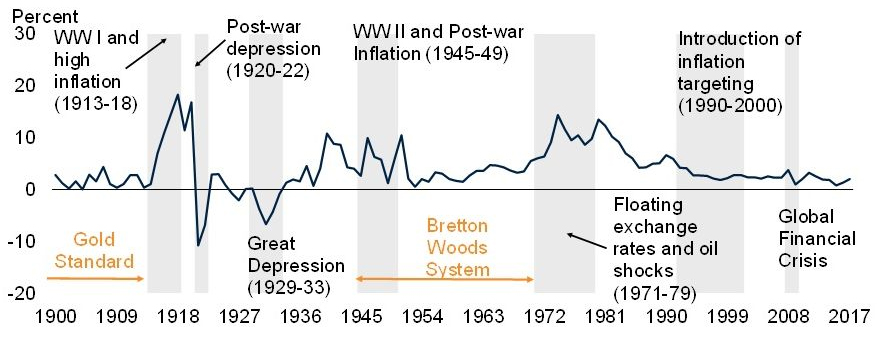

The demise of previous periods of sustained low global inflation is a reminder that low EMDE inflation is by no means guaranteed. Inflation has been low and stable before: during the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system of the post-war period up to 1971 and during the Gold Standard of the early 1900s (Figure 3). However, these two earlier episodes were followed by sharply rising inflation. For example, directly following the low inflation period that ended in the early 1970s, the sharp increase in oil prices in 1973-74 led to a rapid acceleration in global inflation (Kose and Terrones 2015). Global inflationary pressures were accompanied by a significant increase in domestic inflation in developing economies, including those that had experienced low and stable inflation in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Cline 1981).

EMDE policymakers need to recognise the increasing role of the global inflation cycle in driving domestic inflation. Options to help insulate economies from the impact of global shocks include strengthening institutions, including central bank independence, and establishing fiscal frameworks that can both assure long-run debt sustainability and provide room for effective counter-cyclical policies. Low inflation in EMDEs in the past two decades is no guarantee of low inflation in the future.

Figure 3. Low inflation episodes

Sources: World Bank; Ha, Kose, and Ohnsorge (2019)

Note: Median of annual average inflation in a sample of 24 economies for which data are available across the full period.

Note: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

This article first appeared on VoxEU: https://voxeu.org/article/great-disinflation-emerging-and-developing-economies

Further Reading

- Auer, Raphael, Andrei Levchenko, and Philip Sauré (2017), “International Inflation Synchronization through Global Value Chains”, Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

- Cline, WR (1981), World Inflation and the Developing Countries, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Draghi, M (2015), ‘Speech at the Economic Club of New York’, 4 December.

- Fischer, S (2015), ‘Global and Domestic Inflation’, Speech at Crockett Governors’ Roundtable 2015 for African Central Bankers, University of Oxford, Oxford.

- Ha, J, MA Kose, and F Ohnsorge (2019), Inflation in Emerging and Developing Economies: Evolution, Drivers and Policies, Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Kose, MA, E Prasad, K Rogoff, and SJ Wei (2010), ‘Financial Globalization and Economic Policies’, In Handbook of Development Economics, Rodrik, D and M Rosenzweig (eds.), Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Kose, MA, and ME Terrones (2015), Collapse and Revival. Understanding Global Recessions and Recoveries, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Rogoff, K (2003), “Globalization and Global Disinflation”, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, 88 (4): 45-78.

- Rogoff, K (2014), ‘The Exaggerated Death of Inflation’, Project Syndicate, 2 September.

- Taylor, JB (2014), ‘Inflation Targeting in Emerging Markets: The Global Experience’, Speech at the Conference on Fourteen Years of Inflation Targeting in South Africa and the Challenge of a Changing Mandate, South African Reserve Bank, Pretoria.

- World Bank (2018), ‘Global Economic Prospects: The Turning of the Tide?’, June, Washington, DC: World Bank.

17 June, 2019

17 June, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.