The 14th Finance Commission has been hailed as ‘path-breaking’ for recommending larger fund allocations to state governments and giving them more autonomy in spending these funds. In this article, Meera Mehta and Dinesh Mehta highlight that the Commission has also recognised the need to trust and respect local government bodies, and has allocated much larger funds to them. Will this approach work and will state governments cooperate?

The 14th Finance Commission (FC) has been hailed for its path-breaking recommendations in ‘cooperative federalism’1 with a significant increase in the share of state governments in the divisible pool2. What has not been recognised is the fact that the 14th FC has also been quite generous in recommending a larger grant to local governments (includes Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and Urban Local Governments (ULGs)). The allocation to local governments is over twice the amount recommended by the 13th FC, and for ULGs it is nearly three times relative to the 13th FC recommendations.

Deepening federalism: Increased flow of funds to local governments

The 14th FC has given due consideration to the fiscal federalism framework in India by devolving a larger amount to local governments. In doing this, the 14th FC has deepened the decentralisation process that was initiated by the 73rd and 74th3 constitutional amendments. Although as per its mandate, the FC does not directly deal with local governments, it is required to recommend “the measures needed to augment the Consolidated Fund of a State to supplement the resources of the Panchayats and Municipalities in the state, on the basis of the recommendations made by the Finance Commission of the State.” These “measures could be recommendations on both grants in aid as well as suggestions for steps to be taken by the States in this regard.” (Terms of Reference of the Finance Commission). The onus will also be on the state governments to share a larger share of resources they will receive with local governments through unconditional and predictable transfers, as well as to help build local government capacity.

The 14th FC has recommended Rs. 287,436 crore (US$48 billion approx.) for all local governments. This fund is to be distributed across the states on the basis of population and area. The 14th FC has not used the approach adopted by the previous FC of recommending the local government grants as a share of the divisible pool. It suggests that the constitutional provisions regarding the role of Finance Commission do not provide for a share of ‘divisible pool’ for local governments. Hence the allocation to local governments has to be a fixed amount as a grant-in-aid.4

The grant recommended by the 14th FC for local governments is much higher than before, both in amount and in terms of the share of the divisible pool. In doing this, the 14th FC has set the bar much higher than the previous FCs. While there was a clamour by various state and local governments to allocate at least 5% of the divisible pool to local governments, the 14th FC has recommended a grant-in aid for local governments that is equal to an estimated 3% of the divisible pool. This is higher than the recommended allocation of 2.5% by the 13th FC. It is hoped that subsequent FCs will consider higher allocations to local governments, in line with what is practiced in other federal countries such as Brazil (see, for example, Sen et al. 2014 and Arvate et al. 2015). In Brazil, the municipalities receive transfers called Municipalities’ Participation Fund, which are “23.5% of the income taxes and industrialized products taxes that are collected by the federal government" (Arvate et al. 2015).

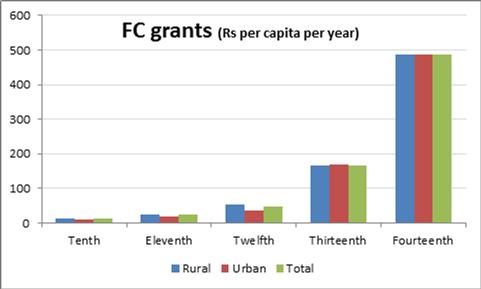

Figure 1. Grants-in aid by 14th FC to urban and rural local governments

It is not very clear how the 14th FC has estimated the quantum of local government grants. It says, “we have worked out the total size of the grant to be Rs. 2,87,436 crores, for the period 2015-20, constituting an assistance of Rs. 488 per capita per annum ”. The only reference made was to the annual per capita estimates ranging from Rs. 195 to Rs. 1,211 for the four State Finance Commissions (SFCs) that were co-terminus with the 14th FC (p.112/9.67) It would have been good to have more explanations on how this amount of Rs. 488 (US$8.1 approx.) is arrived at. Similarly, a rationale might have been provided for using the same amount for both rural and urban areas as the cost of urban public services is likely to be higher. Of course, the equal per capita grant for ULGs recommended by the 14th FC is better than that of its predecessors, which had all given a higher per capita grant to rural local governments.

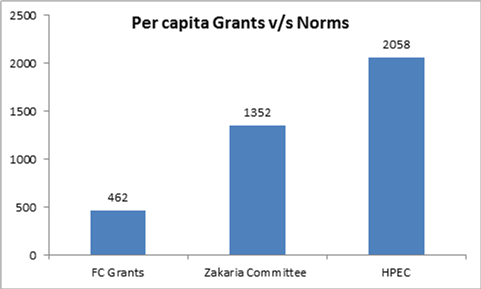

Previous efforts to estimate per capita requirements are based on updating Zakaria committee norms (Zakaria 1963)5. Another effort was made by the High Powered Expert Committee (HPEC) chaired by Isher Judge Ahluwalia, set up by the Ministry of Urban Development in May 2008 for estimating the investment requirement for urban infrastructure services. As we can see in Figure 3, the 14th Finance Commission’s estimates of per capita requirements are far below the recommended amount by these two committees.

Figure 2. Per capita grants to rural and urban local governments by FCs

Source: Based on various Finance Commission documents and population information from relevant Census of India.

Source: Based on various Finance Commission documents and population information from relevant Census of India. Figure 3. Comparison of 14th FC grants for urban local governments with norms

Notes: Zakaria and HPEC (High Powered Expert Committee) estimates have been inflated to 2015. Sources: Based on Finance Commission (2015), Zakaria (1963) and HPEC (2011).

Notes: Zakaria and HPEC (High Powered Expert Committee) estimates have been inflated to 2015. Sources: Based on Finance Commission (2015), Zakaria (1963) and HPEC (2011). Performance-related grants

The 14th FC has continued with the 13th FC recommendation of making these grants available to local bodies in two parts – a basic grant and a performance grant, in a ratio of 90:10 for PRIs and 80:20 for ULGs. The basic grant is an unconditional grant, intended to be used by local bodies to deliver basic services. In the words of 14th FC, “the purpose of basic grants is to provide a measure of unconditional support to the gram panchayats and municipalities for delivering the basic functions assigned to them”.

The 14th FC has kept aside a small portion (10% for PRI and 20% for ULGs) as performance grant. Performance grant is meant to instil improved information on local finances and outcomes as well as focus on increasing own incomes of local governments. The performance grant to urban local governments is to be given if they fulfil three conditions – have their accounts audited, improve own revenues, and publish service-level benchmarks.

The 14th FC observes that reliable information on local government finances is not available in India and the performance grant is conditional upon local governments “making available reliable data on local government receipts and expenditures through audited accounts; and improvement in own revenues”. In addition, the ULBs have to measure and publish service-level benchmarks for basic services.

The 13th FC had listed nine conditions for ULGs to become eligible for performance grant. Most of these conditions were for state governments, rather than local governments. The 14th FC has made a healthy departure in doing away all those conditions (except the one on service-level benchmarks). In doing this, the 14th FC has stuck to its core mandate of ensuring proper accountability of local finances and delivery of services. Insisting on audit of local government accounts is an important step in bringing about transparency and accountability at the local level. In every state, a Local Fund Audit exists as an independent audit department under the administrative control of the finance department of the state government. However, there are severe delays in auditing accounts of all the panchayats and municipalities. In major municipal corporations, an internal audit department exists, which at least ensures some scrutiny, but in other local governments, there is very little check on how the funds are spent.6

The second condition of demonstrating increase in own-source revenue is also important. The limited information suggests an overt dependence of local governments on grants from state governments and the centre. Increasingly, state governments have taken away buoyant sources of revenues from local governments. For example, in Punjab and Rajasthan, the state governments did away with property tax (although it was reinstated later). More recently, Maharashtra has abolished local body tax (LBT). While seeking an improvement in own-revenue sources of local governments, the 14th FC could have also suggested that the state governments should enhance the fiscal domain of local governments. Only then one can expect some stability and growth in local revenues. Further as pointed out by the 13th FC earlier, “The proposed introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) will remove some tax instruments traditionally allocated to local bodies. These include entertainment tax, entry tax, as well as share in stamp duty. It is, therefore, important that local bodies be provided with a buoyant source of revenue as an alternative to fixed grants. This will also be in line with best international practice.”

Of course the local governments need to improve efficiency in collection of key local taxes such as the property tax, as well as user charges for key services. They also need to ensure that these are indexed for regular revision to match increase in service delivery costs.

The third condition laid down by the 14th FC requires an urban local government to “publish the service level benchmarks relating to basic urban services each year and to make them publically available”. This helps ensure a focus on service outcomes, a practice already initiated by over 1,800 ULGs as a result of the earlier 13th FC recommendation. The 14th FC condition will provide an incentive to sustain this. While the 14th FC has put onus squarely on ULGs, both the central and state governments will need to support, strengthen and sustain this process to ensure that the smaller municipalities are able to meet these conditions in a timely manner, while the quality of information is improved over time.

Trust-based approach

The 14th FC recognises the need to trust and have respect for local bodies as institutions of local self-governments. This is in sharp contrast to the treatment often meted out by state governments to local bodies. In most states, local governments have limited administrative and fiscal powers. The lack of capacity of local governments is often cited by the state governments as a reason to further curtail their fiscal powers. In many states, local governments have limited responsibilities, and the decentralisation process envisaged in the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments has largely remained on paper (see, for example, Sivaramakrishna 2000).

In such a climate of distrust of the local governments by the state governments, the 14th FC has put a lot of faith in the state government to operate in a trust-based approach. In view of the impending changes with the introduction of GST, adequate compensation to ULGs for their loss of income will need to be ensured. The past experience has not been very good in this regard. Many state governments, on abolition of octroi (a tax on entry of goods within the city limits) and in some cases even property tax, had promised compensatory grants to ULGs with an annual increase to maintain the buoyancy. However, compensation to local bodies has remained static and is often not released in time.

One hopes that the trust-based approach adopted and recommended by the 14th FC for local governments will also be adopted by the state governments; and that they will transfer all the promised resources to local governments in a timely manner. They will also need to support the smaller local governments and help build their capacity to meet the 14th FC conditions to ensure that the resources do not accrue only to larger ULGs that are able to meet the three simple conditions laid down by the 14th FC for performance grants.

Notes:

- The phrase “cooperative federalism” has been used by the NDA (National Democratic Alliance) government to denote a “vibrant and functional federal structure” where states are given their due.

- The divisible pool is the portion of gross tax revenue which is distributed between the centre and the states. It includes all central taxes excluding surcharges and cess, which the centre is constitutionally mandated to share with the states.

- The 73rd and 74th amendments to the Indian Constitution gave constitutional status to local governments in rural and urban India.

- See para 9.65, Report of the Fourteenth Finance Commission, available at http://www.fincomindia.nic.in.

- Report of the Committee of Ministers constituted by the Central Council of Local Self Government on Augmentation of Financial Resources for Urban Local Bodies, Government of India, New Delhi (Zakaria 1963), is still used as a basis for estimating urban expenditure requirements.

- For example, the CAG (Comptroller and Auditor General of India) website suggests that during the period 2003-04 to 2010-11, only five Audit Reports (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu) on Local Bodies were issued for placement before the State Legislatures); Also see: https://data.gov.in/catalog/cag-local-bodies-audit-reports#web_catalog_tabs_block_10

Further Reading

- Arvate P, E Mattos and F Rocha (2015), ‘Intergovernmental transfers and public spending in Brazilian municipalities’, Working paper 77, REAP, São Paulo School of Business Administration and Center for Microeconomics Applied, Sao Paulo.

- Ghosh RN (n.d.), ‘Accountability of local governments: CAG’s Initiatives and the Challenges Ahead’, Research Paper, International Centre for Information Systems and Audit (iCISA), Office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India

- Finance Commission (2015), ‘Fourteenth Finance Commission’, Government of India.

- Sen, Tapas et al. (2014), ‘Intergovernmental Finance in Five Emerging market Economies’, Report prepared for the Fourteenth Finance Commission, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

- Sivaramakrishna, KC (2000), ‘Power to the people – The politics and progress of decentralization’, KOnarak Publication for the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi.

- The High Powered Expert Committee (HPEC) (2011), ‘Report on Indian Urban Infrastructure and Services’, Committee for Estimating the Investment Requirements for Urban Infrastructure Services.

- Zakaria, R (1963), ‘Report of the Committee of Ministers constituted by the Central Council of Local Self Government on Augmentation of Financial Resources for Urban Local Bodies’, Government of India, New Delhi.

27 April, 2015

27 April, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.