A large-scale rural roads programme in India has provided access to over two-third of villages that lacked a paved road in 2001. Do citizens reward incumbent governments electorally for these improvements in connectivity and well-being? Using data from elections and roads provision for 2000-2017, the article suggests that citizens do not vote on the basis of policy even when they have access to rich information about the policy’s provision.

The last 20 years have transformed Indian policy. The country has seen the launch of RTE (The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act), PMGSY (Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana), and Ujjwala Yojana, which have singularly focused on improving basic services for the rural poor. But have India’s rural voters responded electorally to these policies? A positive answer to this question is promising for not only India’s democratic future, but also for how democracy is viewed worldwide. Surprisingly, while there is a great deal of research that documents that Indian citizens vote on ethnic or clientelistic lines (for example, see Chandra 2004), empirical tests of the converse, that is, the empirical question that citizens would vote for policy provision in the Indian context, remains untested. I address this gap by showing that Indian citizens do not vote on basis of policy and they do not do so even when they have access to rich information about the policy's provision.

Roads provision as a most likely case to observe electoral effects in India

A study of rural roads is theoretically well-placed to examine whether citizens would vote for policy, as a rich literature suggests that roads present a most likely case for policy voting, implying it has high generalisability to other development policies. That is, if we do not observe accountability for roads, it is unlikely that we observe it for other policies.1

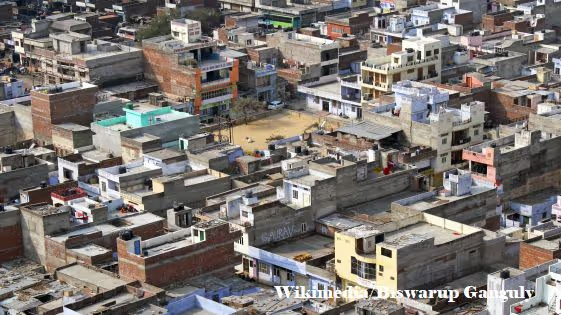

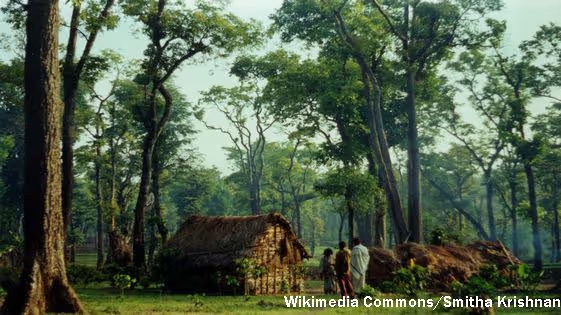

PMGSY roads have been the largest visible change in the rural corridors of the country in India’s entire post-colonial history, a comparative one being the provision of railways. The scale of provision makes these roads impossible to ignore: the average Indian village has a diameter of 2.1 km, and the average road built through this programme is 4.4 km long. Figure 1 below shows the visible changes in villages before and after receiving PMGSY roads. Moreover, there is causal evidence that the poor benefit from PMGSY roads not only economically but also through access to State services in health, education, and agriculture.2 PMGSY roads typify aspects that improve accountability.

Figure 1. PMGSY roads in previously unconnected regions (before – top; after – bottom)

Exogenous roads provision

While roads constitute a policy that presents a strong case to observe accountability, these same features make them a lucrative electoral resource that is prone to political targeting and challenging to study. Fortunately, the PMGSY programme offers a rare source of exogeneity (external variation) to deal with this perennial empirical challenge. Despite the fact that political influence is omnipresent in the programme, pre-determined and arbitrary population-based thresholds at least partly influence roads provision. I construct an instrument to isolate the effect of roads provision that is exogenous to political targeting in allocation, and improve inference by focusing on the change in incumbents' vote share within the administrative level at which road plans are prepared.

Unprecedented use of informational devices in PMGSY

In addition to this exogeneity in policy provision, the programme improved transparency and information for citizens in a way that has never been done before in any such context worldwide. As seen in Figure 2, each road in the programme is verified to be accompanied by special logo boards, signage, and information boards. An analysis of internal quality data collected from the National Rural Road Development Agency (NRRDA) shows that approximately 90% of all roads are verified to have a high-quality logo and/or information board.

Figure 2. PMGSY roads signage across Indian states

2a. Logo board in Haryana

2b. Full sign board in Orissa

2c. Extensive sign board in Jharkhand

Source: (a) and (b) PMGSY website, and (c) World Bank Development blog.

Moreover, the programme left no stone unturned to make a direct link between roads provision and local politicians. Public events in villages were officially sponsored where politicians laid the foundation of the PMGSY road at the start and inaugurated the road at its completion. A citizen monitoring report finds that a large majority of citizens cite boards as a key source of information about PMGSY and can distinctly identify PMGSY roads. As per a citizen monitoring report compiled in 2011 by the Political Affairs Centre, citizens also report experiencing benefits, high awareness, and daily usage of these roads (Public Affairs Centre, 2011).

Figure 3. Politicians lay the foundation stone for the construction of PMGSY road.

Source: Daily Excelsior; 23 February 2017.

Data

To examine the electoral response to roads provision, I leverage rich granular road-level data on approximately 180,000 all-weather rural roads that were provided for the first time in India between 2001 and 2017. I use fuzzy name matching to geo-code this roads-level data to 600,000 villages from the Indian Census 2001 and 2011. I then spatially aggregate this data to national- and state-level electoral constituencies for elections between 1998 and 2017 in 14 large Indian states.3 This dataset covers over 90% of India's total population, approximately 11,000 electoral races, and almost the entire duration of the roads programme. An advantage of a constituency-level analysis is that, by pooling observations, I account for positive spillover effects of roads visibility. Because, these roads connect villages to markets, citizens are likely to be positively exposed to roads outside their immediate surroundings.

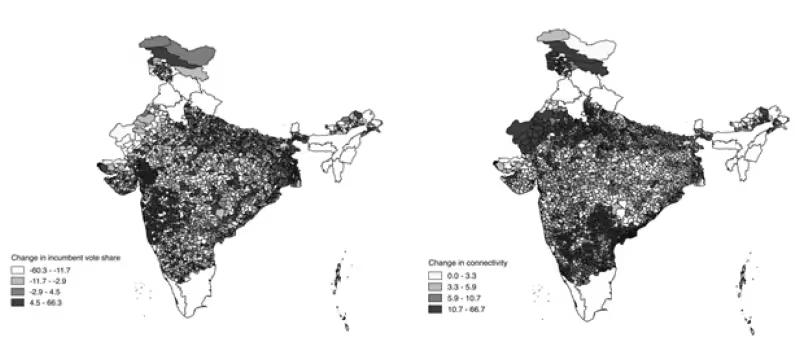

The figure on the right below shows the massive change in connectivity across India and over time, and the figure on the left shows the change in state-level incumbent vote share, both in the pre-delimitation period for state assembly constituencies. A lack of correlation between the two maps is apparent.

Figure 4. Change in state-level incumbent party vote share and change in connectivity, in the pre-delimitation period

Notes: The right panel shows change in incumbent party vote share (measured as % difference in incumbent party vote share in a particular constituency between two consecutive elections) in state-level elections in the pre-delimitation period (1999-2008). The left panel shows the change in connectivity (measured as % of villages connected in a constituency) in the corresponding electoral periods.

Yet an alternative possibility is that citizens only care about roads provision in their immediate local areas. Further, if citizens' exposure to roads in their broader surroundings leads those who do not get roads to punish the incumbent, this would lead to negative spillover effects of roads provision in local areas where citizens lack roads, and aggregation may average out these micro-dynamics. To address these concerns, I examine accountability at the level of ‘treatment’ (roads provision), that is, at the booth-village level. I do so in one of the most poorly connected and the largest Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (UP). Linking the geo-coded roads dataset with the geo-coded booth-level electoral dataset for over 100,000 booths with roughly 980 voters each, I estimate the effect of roads provision on the change in booth-level vote share within a politicians' constituency at very local levels. Figure 5 below shows change in Samajwadi Party’s (SP) vote share at the booth level in comparison with village-level roads provision in Uttar Pradesh. The two maps show a lack of any correlation, while the left map documents the fact that the strong incumbency electoral disadvantage travels to the booth level.

Figure 5. Change in Samajwadi Party’s vote share at the booth level in comparison with village-level roads provision in Uttar Pradesh

Notes: The right panel shows booth-level change in SP party vote share between 2012 and 2017. Lighter dots mean that SP lost vote share in 2017 relative to 2012, while darker dots represent increase in votes. The left panel marks the villages that received a PMGSY project between 2000 and 2017 as black.

Findings

Despite the compelling case roads provision presents for accountability, my research finds that roads provision fails to boost electoral support for the incumbent, across space, levels of analysis, and over time; and the zero effect is precisely estimated. Indian citizens did not vote for roads provision in either state elections or national elections, nor did Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the political party that announced the programme gained electorally from programme announcement. Booth level results in UP at highly disaggregated levels also reassert the constituency level findings.

These results contrast with quasi/natural-experimental studies that document the significant effects of infrastructure provision even in conflict-ridden or authoritarian contexts (Berman, Shapiro and Felter 2011, Voigtlaender and Voth 2014), with observational evidence from developing countries (Harding 2015), and with evidence for incumbent support for public policies found in other developing contexts (Labonne 2013, Pop-Eleches and Pop-Eleches 2012).

Using data on variation in quality of programme implementation and exploiting the regional diversity of Indian politics I can rule out that the reason roads provision fails to have an effect on incumbent support is not because citizens are driven by corruption concerns or are unable to attribute roads provision. I find that citizens do not respond to variation in quality of roads: they neither reward good-quality roads nor punish for poor quality. The possibility that presence of both MPs (Members of Parliament) and MLAs (Members of Legislative Assembly) might lead to attribution errors also finds no support.

What does this say about Indian politics?

India is a substantive case for scholars of democracy and development. While scholars are divided on whether Indian citizens' cast their vote or vote their caste, there is also growing belief that Indian citizens have started to reward good performance. This research contributes to this debate by providing strong evidence from the last 20 years that Indian citizens do not vote on basis of policy provision.

There is also limited understanding of the widely documented incumbency disadvantage in India, often referred to as the cost of ruling. Citizens’ lack of voting on policy performance suggests why the incumbency does not bring an advantage in the Indian context. Incumbents have a comparative advantage over oppositions because they can use their policies to signal competence more effectively, while opposition cannot do so. However if citizens' do not take performance into account, incumbency does not bring this comparative advantage.

Implications

The findings have important implications for democratic governance amongst, other debates. With the rise in infrastructure provision in many countries in Africa, these findings should worry scholars of democratic governance. Electoral incentives, generated through accountability mechanisms, are posited as a key means to improving service delivery in developing democracies (World Bank, 2003). However, if voters remain unresponsive to policy provision, electoral incentives for public goods provision or improving service delivery, may diminish over time, leading to abandonment or poorer implementation of these crucial programmes.

Notes:

- Existing literature suggests that voters enforce accountability for outcomes that: enhance prosperity; signal competence; for which politicians claim credit; and that are visible. PMGSY roads typify these aspects. For a review of electoral accountability see Healy and Malhotra (2013), and for a specific discussion on why roads have these electoral properties, see Harding (2015).

- Aggarwal (2018a) finds that households in areas where roads were provided under PMGSY report lower prices, increased availability of non-local goods, increased use of agricultural technologies, and school enrolment gains for younger children. Asher and Novosad (2018) report more conservative estimates and find that roads only allow workers to obtain non-farm work. Perhaps the most crucial gains have been with respect to education and health improvements, Adukia, Asher and Novosad (2019) finds that in regions that get PMGSY roads, children stay in school longer and perform better on standardised exams. Roads have also improved women’s mobility and access to healthcare (Aggarwal 2018b).

- India underwent electoral border redistricting in 2008, which drastically altered constituency boundaries at both electoral levels. This results in a break in the dataset, and I create two distinct datasets for pre- and post- delimitation at the both state and national levels.

Further Reading

- Adukia, Anjali, Sam Asher and Paul Novosad. (2019), “Educational Investment Responses to Economic Opportunity: Evidence from Indian Road Construction”, Forthcoming, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

- Asher, Sam and Paul Novosad. (2018), “Rural Roads and Local Economic Development”, Conditionally accepted, American Economic Review.

- Berman, Eli, Jacob N Shapiro and Joseph H Felter. (2011), “Can Hearts and Minds Be Bought? The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq”, Journal of Political Economy, 119(4): 766–819. Available here.

- Chandra, Kanchan. (2004), Why ethnic parties succeed: Patronage and ethnic head-counts in India, Cambridge University Press.

- Harding, Robin. (2015), “Attribution and Accountability: Voting for roads in Ghana”, World Politics, 67(4): 656–689.

- Healy, Andrew and Neil Malhotra (2013), “Retrospective Voting Reconsidered”, Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1): 285–306.

- Labonne, Julien (2013), “The local electoral impacts of conditional cash transfers: Evidence from a field experiment”, Journal of Development Economics, 104: 73–88.

- Public Affairs Centre (2011), Citizen Monitoring and Audit of PMGSY Roads: Pilot Phase II. Available here.

- Pop-Eleches, Cristian and Grigore Pop-Eleches (2012), “Targeted Government Spending and Political Preferences”, Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 7(3): 285–320. Available here.

- Voigtlaender, N and H-J Voth (2014), ‘Highway to Hitler’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working paper no. 20150.

- World Bank (2003), ‘World Development Report 2004: Making services work for poor people’, World Bank Group, Washington, DC.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.svg)

.svg)

.svg)