The Indian government launched the School Sanitation and Hygiene Education programme in 1999 to build latrines in schools. Analysing data from nearly 140,000 schools in 2003 - some of which received a latrine and some that did not - this article shows that latrine construction positively impacted educational outcomes like enrolment, dropout rates, and number of students who appeared for and passed exams.

During my research on the impact on education of sanitation facilities in schools in India, I interviewed hundreds of children and their parents,[1] as well as 140 school headmasters. The contrast between the parent/child view and that of the headmasters could not have been more striking.

Teenaged girls described the joys and wonders of education and explained how much they loved learning. Many, however, were not attending classes. When asked why, their replies centred on a common theme: privacy, safety, and health problems associated, in part, with a lack of private sanitation facilities. Some explained that they stayed home during their periods and that they had missed too many days every month, including key tests, leading to their expulsion. Other girls felt unsafe relieving themselves outside behind bushes, with some describing assaults by boys. In some cases, the fear of an assault was enough to keep parents from sending their daughters to school. Those who attended would often refrain from eating or drinking during the day and would eventually become lightheaded or otherwise ill from dehydration and hunger. They also put themselves at high risk for urinary tract infections and kidney stones by holding back the urge to relieve themselves.

On the other hand, of the 140, mostly male, headmasters that I interviewed, only three said that a lack of sanitation facilities was a problem at their schools.

Anecdotally, these conflicting views reveal that a lack of sanitation facilities is negatively impacting education, and that a lack of concern by education authorities is part of the problem. We have much more than anecdotes, however, to support this claim. The Indian government and NGO community have tried to address this sanitation gap since the turn of the century, and these efforts provide a large-scale setting with large administrative and survey datasets that enable important insights into the link between sanitation facilities and education outcomes.

My research (Adukia 2017) is the first effort to assess the government’s programmes through these data, reveals that there are real benefits to simply building sanitation facilities at more schools. School attendance improves at schools where latrines are added, and these gains are not limited to pubescent girls, as many assume. Both girls and boys of all ages, as well as female teachers, benefit from the addition of sanitation facilities, which can also prevent groundwater contamination and help ensure a healthier environment for students and teachers.

The case for privacy, safety, and health

In 2000, about 20 million Indian children did not attend school, roughly 20% of all out-of-school children worldwide. That same year, the Indian government began promoting universal primary education through a World Bank-sponsored programme, and by 2013, the number of out-of-school Indian children fell to 6 million, or about 11% of the worldwide total.

One way the Indian government hoped to increase school attendance, especially among pubescent-aged girls, was to build sanitation facilities at schools. In 1999, when roughly half of Indian schools had sanitation facilities, the School Sanitation and Hygiene Education (SSHE) programme was launched as part of the broader Total Sanitation Campaign of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, to improve sanitation facilities throughout India. SSHE emphasised school sanitation as a mechanism to bring about broader social change in sanitation practices. In particular, SSHE sought complete school latrine coverage in rural areas for two primary reasons: to improve health outcomes through reductions in disease and worm infestation, and to reduce security risks for girls, especially for pubescent-age girls.

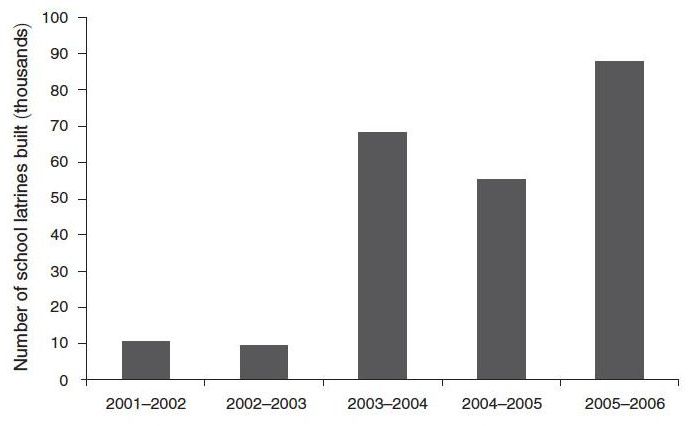

SSHE’s impact was immediate and large. Figure 1 illustrates the jump in latrine building with total new units reaching nearly 90,000 three years after the programme’s start.

Figure 1. Number of school latrines built, by academic year

But what impact did such construction have on education outcomes? To answer this question, I analysed data from nearly 140,000 schools in 2003, some of which received a latrine and some that did not, providing a natural comparison group under certain assumptions. The results were striking:

- School latrines increased enrolment and lowered dropout rates for all students, not just pubescent-age girls. For example, enrolment increased by 12% in primary schools (1st-5th grades) and 8% in upper-primary schools (6th-8th grades). In the sample of schools in this study, this translates to an overall increase of 607,000 primary school students and 75,000 upper primary-school students.

- These changes are also reflected in the increased number of students who appeared for and passed the middle school board exam.

- A latrine generally increased female enrolment more than male enrolment.

- Inconsistent with a narrow focus on menstruation, younger girls and boys experienced larger benefits than older children from the presence of a latrine.

- While the impact of educational infrastructure interventions generally can often fade over time, the enrolment impact of latrines was still present or even slightly stronger three years later. This is particularly noteworthy, as the latrine-construction initiative did not specifically target latrine maintenance.

While these overall positive results are promising, a closer look at the data reveals that the type of sanitation facility matters. Some schools received resources to build unisex latrines, whereas other schools received resources to build sex-specific latrines. I find that unisex latrines are mostly sufficient at younger ages with relatively smaller additional gains from sex-specific latrines. For younger children, privacy may be less of an issue and many of the gains from adding latrines may come from improved sanitation and health outcomes.

At older ages, however, separate latrines become crucial. Pubescent-age girls benefit little from unisex latrines, and their enrolment increases substantially after the construction of separate sex-specific latrines, which suggests that privacy and safety concerns may be central to older girls’ decision-making. And these benefits accrue to female teachers: the addition of sex-specific latrines increases attendance by female teachers and may encourage more women to become teachers – a possible benefit to female students.

And we can’t forget about the boys. Policymakers are mostly concerned about pubescent girls, and for good reason, but boys – especially younger ones – may also benefit from the addition of sanitation facilities. Boys can be the victims of bullying and teasing, as well as harassment and molestation, and research has suggested that boys also benefit from access to privacy.

Toilets in schools matter

Policymakers worldwide have long noted the benefits of eliminating gender disparity in education as a method of improving the lives of the poor. Access to schools provides benefits beyond education, including improved economic and social outcomes later in life for those who merely attend school, regardless of how well they perform in class. In other words, simply getting girls to school and keeping them there has benefits for them and for society.

My research shows that adding such basic infrastructure as sanitation facilities increases the enrolment of both girls and boys, and that the type of latrine matters. Pubescent-age girls benefit substantially from the construction of sex-specific latrines but benefit little from unisex latrines. Privacy and safety matter sufficiently for girls at older ages that school sanitation only reduces gender disparities with the construction of sex-specific latrines. By contrast, unisex latrines are mostly sufficient at younger ages. Indeed, school latrines can have substantial positive impacts on younger children, who are most vulnerable to sickness from lack of waste containment.

As governments continue to devote resources to improving school sanitation, this analysis has implications for how scarce resources might be directed to greater effect. In India, for example, the recent Indian government ran on a campaign slogan of “toilets before temples”, launching the Swachh Bharat: Swachh Vidyalaya (“Clean India: Clean Schools”) initiative to provide universal access to sex-specific latrines in all government schools, echoing the earlier SSHE programme.

These lessons from India likely also apply to other countries where basic school infrastructure is lacking. I analysed the estimated impact of latrines across Indian districts that differ substantially in average per capita income and found that the results were similar. While suggestive only, this observed relationship between sanitation and education across different income levels means that the relationship could hold in other countries that share demographic characteristics with India.

While there are many deep roots to problems of gender inequality in developing countries, it is a telling fact that one-third of schools worldwide lack restrooms. Improving school sanitation provides one mechanism to increase gender equality by targeting disproportionately high dropout rates among pubescent-age girls. However, in considering the importance of school sanitation, these impacts on pubescent-age girls should not obscure the importance of sanitation for younger boys and girls.

Societal inequality is exacerbated when one in five children worldwide do not complete upper primary school; understanding their motivations to drop out is crucial. We know from their stories, and now we know from the data, that the simple construction of sanitation facilities can improve school attendance and provide the privacy, safety, and health that all children – and adults – deserve.

Note:

- I conducted structured interviews primarily in four Indian states: Madhya Pradesh (MP), Andhra Pradesh (AP), Tamil Nadu (TN), and Uttar Pradesh (UP). Research participants were drawn from a convenient sample found in fields (farmers, fieldworkers), households (parents, children), schools (principals, children), and roadside shops (shop owners, customers). In MP, research participants were located in the rural districts of Sehore and Vidisha. The sample included 53 private citizens (farmers, fieldworkers, shopkeepers, parents, etc.), 20 government officials, six school officials, and one bank manager. The research participants in AP were located in the rural Nalgonda district. The sample included 34 private citizens, and six school officials. In UP, eight private citizens, and three school officials were interviewed in the rural Bhakshi Ka Talab area outside of Lucknow. In TN, interviewees were 10 private citizens who resided in the rural Tiruvallur district. In addition to the interviews, I conducted a survey of 133 households in Tiruvallur. Interview lengths ranged from five minutes to two hours, guided by interview methodologies discussed by Seidman (1998), and Emerson, Fretz and Shaw (1995).

Further Reading

- Adukia, Anjali (2017), "Sanitation and education", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics2 (2017): 23-59. Available at: https://harris.uchicago.edu/files/adukia_sanitation_and_education.pdf

- Emerson, RM, RI Fretz, and LL Shaw (1995), Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Seidman, I (1998), Interviewing as Qualitative Research, Teachers College Press, New York.

20 August, 2018

20 August, 2018

By: Viswa 17 February, 2019

Nice